Marry me. The question she hadn’t known how to ask him. Jenny bundled into Elijah’s arms. “Yes. Yes to the family and the home, yes to becoming your wife. Nothing would make me happier.”

In the small parlor curiously devoid of pink or red, Elijah held her close, which was very good indeed, because Jenny felt as if she’d fly apart if he let her go, so great was her happiness.

“We can make Paris our wedding journey,” Elijah said, kissing her cheek. “Though I’d spare you a winter crossing if I could.”

She aimed for his mouth and ended up kissing his chin. “A New Year’s crossing, please.”

His hand slid down her back to cup her derriere and draw her closer. “I can’t wait a year.”

“This New Year.”

“Better,” he growled against her mouth. “Nearly tolerable, in fact. Kiss me.”

She did, and she was still kissing him when a tap sounded on the door.

Elijah smiled crookedly and eased away, pausing to tuck a lock of Jenny’s hair behind her ear. When he opened the door, Jenny saw his parents and Her Grace in the hallway.

The marchioness led the parental parade into the parlor. “Excellent! You are showing Lady Jenny your sketches. Her Grace tells me she has a similar collection, most of them done by her daughter.”

“Perhaps it will be a family tradition, then,” Elijah said. He slipped his arm around Jenny’s waist. “I am happy to inform the assemblage that Lady Genevieve has consented to be my wife. His Grace led me to believe my suit would be accepted, and Genevieve has indeed agreed.”

His Grace? As Jenny accepted a hug from her mother, she spared a thought to wonder when His Grace-of-the-never-ending-journey might have said such a thing.

“Welcome to the family,” Lord Flint said, bowing over Jenny’s hand. “Elijah, I suggest you complete the ceremony before you allow your lady to meet your brothers.”

“Flint, that is not funny.” Her ladyship bussed both of Jenny’s cheeks. “Now that Elijah has found a lady willing to put up with him, his brothers might well see the blessings to be enjoyed in the state of holy matrimony. Genevieve, well done.”

As Lord Flint led them back to the paneled parlor and poured generous cups of wassail, Jenny stayed by Elijah’s side.

“Do you really want to see Paris, my dear?” Elijah had bent close to whisper his question, while their mamas debated the use of the Windham chapel or the facilities at Flint Hall.

“Paris can wait. There are other things I want to see more.”

“Such as?”

Jenny gave him a very direct look. “If I’m to give up my art, then I expect certain consolations, Elijah.”

He set his drink aside. “Papa’s brew has addled your wits. What nonsense is this?”

“Someday you will become a Royal Academician, but not if your lady wife is showing up at Venetian breakfasts with paint on her fingers. I understand that.”

He studied her for a moment, as if trying to puzzle out which pigments would accurately depict her hair in strong sunlight. “You would stop painting, stop drawing, stop even embroidering?”

She hesitated only an instant before nodding. “I expect that home and family you allude to will keep me adequately occupied.”

“My mother bore twelve children, six of them boys.”

What did that have to do with anything? “I look forward to meeting your brothers and sisters.”

“Come with me, Genevieve. If you think a few babies will excuse you from your art, then you have much to learn as a future marchioness of Flint.”

He dragged her from the parlor, barely giving Jenny time to set her drink down, and hauled her up two flights of stairs and down a long hallway.

“This is the portrait gallery, also the cricket pitch, skittles hall, and pall-mall pitch, among others.” He opened a carved door and ushered Jenny into a room at least ninety feet long. “It’s cold. Take my coat.”

Frigid was a better word, but as Jenny gathered Elijah’s coat around her shoulders, she was content to endure the cold.

“You lot!” Elijah called to a group at one end of the room. “Clear out! I’m proposing to my prospective wife.”

Hoots and whistles resulted, and smiles from the young ladies, two of whom looked exactly alike but for their attire. As Elijah’s siblings filed past Jenny, the youngest fellow winked at her, and Elijah cuffed him on the back of the head.

“Pru is the worst,” Elijah said as he closed the door. “You must not allow him to cozen you, ever.”

Jenny made no reply, because she was too busy staring at the chamber before her. This was not a collection of a dozen or so renderings of the various Lords of Flint, but rather an exhibition, a room stacked as high as any in Carlton House with portraits, still lifes, landscapes, ensemble pieces, and the occasional academic study.

“Mother finds time to paint,” Elijah said. “You will too.”

Jenny turned a complete circle, taking in dozens upon dozens of completed works. They weren’t all brilliant—some were clearly experiments, others were quick efforts more whimsical than beautiful—but they all showed talent.

“She hid her talent for you,” Jenny said, hurting for the marchioness. “She did not want the Academy taking you into further dislike because she was so talented.”

“You’re wrong.” Elijah laced his arm with Jenny’s and started her on a tour of the room. “Mama has given away any number of paintings. She embroiders the most fantastic receiving blankets and christening gowns you’d ever want to see. What I’ve concluded is that she put aside the Academy’s notice because it really did not matter. In her day, she might have lobbied for membership, but she chose to be my father’s marchioness instead.”

Jenny gazed at smiling children, doting ancestors, Lord Flint on a bay hunter, Elijah as a young boy—she was going to study that one at length. “She made the better choice. The wiser choice.”

“She did, and we will too. There’s an epistle downstairs bearing the seal of the Royal Academy, and it has my name on it. I’m going to decline the nomination.”

As she had turned away from Paris?

“Accept it, Elijah. For your parents, for me, for yourself. You accept this gesture of recognition, and I will not give up my art.” He sent her a look that revealed his uncertainty, and Jenny fell in love with him all over again.

“You’re sure? I will never hide my wife’s talents, Genevieve. Not for them, not even for you would I do such a thing.”

Jenny wrapped her arms around him. “Your wife would not ask it of you, nor would she allow you to hide yours. But, Elijah?”

“My love?”

“As much as I look forward to sharing a studio with you and arguing with you about the proper use of the color green, I suspect we’re going to have a very large family.”

Elijah’s smile was devilish and sweet. “I suspect we will too.”

They shared several wonderful studios thereafter—at Flint Hall, at Morelands, at their London residence, and in the homes of each of Jenny’s siblings, Elijah having developed a preference for juvenile portraits and subjects being available in quantity.

They also argued over the proper use of every color in the rainbow, and over many other things besides.

And they had a very large, happy family, the first child—Rembrandt Joshua Harrison—making his appearance exactly nine months after the wedding.

Read on for an excerpt from Grace Burrowes’s

bestselling Scottish Victorian series

The MacGregor’s Lady

Available February 2014

from Sourcebooks Casablanca

Hannah had been desperate to write to Gran, but three attempts at correspondence lay crumpled in the bottom of the waste bin, rather like Hannah’s spirits.

The first letter had degenerated into a description of their host the Earl of Balfour. Or Asher, Mr. Lord Balfour. Or whatever. Aunt had waited until after Hannah had met the fellow to pass along a whole taxonomy of ways to refer to a titled gentleman, depending on social standing and the situation.

The Englishmen favored by Step-papa were blond, skinny, pale, blue-eyed and possessed of narrow chests. They spoke in haughty accents, and weren’t the least concerned about surrendering rights to their monarch, be it a king who had lost his reason or a queen rumored to be more comfortable with German than English.

Balfour was neither blond, nor skinny, nor narrow-chested. He was quite tall, and as muscular and rangy as any backwoodsman. He did not declaim his pronouncements, but rather, his speech had a growl to it, as if he were part bear.

The second draft had made a valiant attempt to compare Boston’s docks with those of Edinburgh, but had then doubled back to observe that Hannah had never seen such a dramatic countenance done in such a dark palette as she had beheld on Balfour. She’d put the pen down before prosing on about his nose. No Englishman ever sported such a noble feature, or at least not the Englishmen whom Step-papa forever paraded through the parlor.

The third draft had nearly admitted that she’d wanted to hate everything about this journey, and yet, in his hospitality, and in his failure to measure down to Hannah’s expectations, Balfour and his household hinted that instead of banishment, a sojourn in Britain might have a bit of sanctuary about it too.

Rather than admit that in writing—even to Gran—that draft had followed its predecessors into the waste bin. What Hannah could convey was that Aunt had not fared well on the crossing. Confined and bored on the ship, Enid had been prone to frequent megrims and bellyaches and to absorbing her every waking hour with supervision of the care of her wardrobe.

Leaving Hannah no time to see to her own—not that she’d be trying to impress anybody with her wardrobe, her fashion sense, or her eligibility for the state of holy matrimony.

Her mission was, in fact, the very opposite.

Hannah sanded and sealed a short note mostly confirming their safe arrival, the earl having graciously given her the run of his library.

But how to post it?

Were she in Boston, she’d know such a simple thing as how to post a letter, where to fetch more tincture of opium for her aunt, what money was needful for which purchases.

“Excuse me.” The earl paused in the open doorway, then walked into the room. He had a sauntering quality to his gait, as if his hips were loose joints, his spine supple like a cat’s, and his time entirely his own. Even his walk lacked the military bearing of the Englishmen Hannah had met.

Which was both subtly unnerving and… attractive.

“I’m finished with your desk, sir.” My lord was probably the preferred form of address—though perhaps not preferred by him. “I’ve a letter to post to my grandmother, if you’ll tell me how to accomplish such a thing?”

“You have to give me permission to sit.” He did not smile, but something in his eyes suggested he was amused.

“You’re not a child to need an adult’s permission.” Though even as a boy, those green eyes of his would have been arresting.

“I’m a gentleman and you’re a lady, so I do need your permission.” He gestured to a chair on the other side of a desk. “May I?”

“Of course.”

“How are you faring here?”

He crossed an ankle over his knee and sat back, his big body filling the chair with long limbs and excellent tailoring.

“Your household has done a great deal to make us comfortable and welcome, for which you have my thanks.” His maids in particular had Hannah’s gratitude, for much of Aunt’s carping and fretting had landed on their uncomplaining shoulders.

“Is there anything you need?” His gaze no longer reflected amusement. The question was polite, but the man was studying her, and Hannah felt herself bristle at his scrutiny. She’d come here to get away from the looks, the whispers, the gossip.

“I need to post my letter. When do we depart for London?”

He picked up an old-fashioned quill pen, making his big hands look curiously elegant, as if he might render art with them, or music, or delicate surgeries.

“Give me your letter, Miss Hannah. I’ve business interests in Boston and correspond frequently with my offices there. As for London, we’ll give Miss Enid Cooper another week or so to recuperate, and if the weather is promising, strike out for London then.” He paused and the humor was again lurking in his eyes. “If that suits?”

She left off studying his hands, hands which sported neither a wedding ring nor a signet ring. What exactly was he asking?

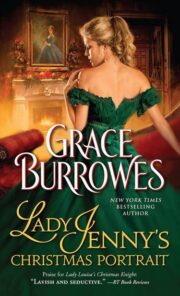

"Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait" друзьям в соцсетях.