“No,” answered Lady Wychwood. “I am afraid I don’t know, Jurby.”

Nothing more was said between them, but much that was unspoken was understood.

Dr Tidmarsh, when he arrived less than an hour later, spent much longer with Miss Wychwood than he had found it necessary to spend either with Miss Farlow or with Tom, and when he came downstairs again, he told Lady Wychwood that while Miss Wychwood was suffering from no more serious disorder than influenza the attack was a severe one. He had found her pulse tumultuous; she was extremely feverish; and although he was confident that the medicine he had prescribed for her would soon reduce the fever, he warned her ladyship that it was possible—even, he was sorry to say, probable—that she might become a trifle delirious as the day wore on. “I tell you this, my lady, because I don’t wish you to be alarmed if she should wander a little in her mind. I assure you there is no cause for alarm! I hope that she will sleep, but if she should be restless you may give her a few drops of laudanum. Rather, I should say, her maid may do so, for you will, I trust, abide by your wise determination to stay out of the way of infection. I must add that the fear that you, or Miss Carleton, should run the slightest risk of taking influenza from her is preying on her mind, which is very undesirable, as I am persuaded you must recognize. In short, I consider it to be of the first importance that she should be kept as quiet as may be possible. The fewer people to enter her room the better it will be for her, while she is so feverish.”

“No one shall enter it without your permission, doctor,” said Lady Wychwood.

She was agreeably surprised, when she reported the doctor’s words to Lucilla, to see a look of chagrin in Lucilla’s face, for she had been inclined to think that for all her engaging ways and pretty manners she wanted heart. She had certainly not expected tears to spring to Lucilla’s eyes when she was told that she must not enter Miss Wychwood’s room until all danger of infection was over, and she was a good deal touched when Lucilla said forlornly: “May I not nurse her, ma’am?”

“No, my dear, I am afraid not. Jurby is going to nurse her.”

“Oh, yes, but I could help her, couldn’t I? I promise I would do just as she bade me, and even if she doesn’t think I’m old enough to nurse people I could at least sit with Miss Wychwood while Jurby rests, or goes down to eat her dinner, couldn’t I? I can’t bear it if I am not allowed to do anything,because I do love her so much, and she does everything for me!”

Lady Wychwood was moved to put an arm round her, and to give her a slight hug. “I know how hard it is for you, dear child,” she said sympathetically. “I’m in the same case, you know. I would give anything to be able to look after my sister, but I must not.”

“But you have your baby to look after, ma’am, which makes it quite different!” Lucilla said urgently. “I haven’t got a baby, or anyone who would be a penny the worse for it if I caught influenza!”

“I can tell you of one who would be the worse for it, and that is my sister,” said Lady Wychwood. “Jurby tells me that she is in a great worry about us, and has made Jurby promise not to permit either of us to go near her. I know you wouldn’t wish to distress her—and to tell you the truth I think she is feeling too poorly even to wish to see anyone but Jurby. Wait until she is rather better! The instant Dr Tidmarsh tells us that she is no longer infectious I promise you shan’t be kept out of her room. As for sitting with her now, she isn’t ill enough to make it necessary for someone to be always with her, you know. Indeed, from what I know of her, I am very sure she would find it very irksome never to be left alone!”

Lucilla heaved a doleful sigh, but submitted, saying humbly that she didn’t mean to be troublesome. Lady Wychwood then had the happy notion that she might like to go out with Mrs Wardlow, who had shopping to do, and buy some flowers to put in Miss Wychwood’s room. The suggestion took well. Lucilla’s face brightened, and she exclaimed: “Oh, yes! I should like that of all things, ma’am! Thank you!” But when Lady Wychwood further suggested that she should write a note to Corisande to ask her to ride with her on the following morning, she shook her head, and said decidedly that nothing would prevail upon her to go pleasuring while Miss Wychwood was ill.

It was not to be expected that Miss Farlow would submit as meekly to the doctor’s decree, and nor did she. Hardly had Lucilla tripped out with the housekeeper than she subjected Lady Wychwood to an extremely trying half-hour, during which she complained passionately of Jurby’s insolence in daring to shut her out of Annis’s room; declared her intention of taking care of Annis herself, whatever the doctor said; delivered herself of a moving but muddled speech in support of her claims to be the only proper person to have charge of the sick-room, in which she several times begged Lady Wychwood to agree that whatever anyone said blood was thicker than water; and ended an agitated monologue by pointing out, in triumph, that it was of no use for her ladyship to talk of the danger of infection, because she had already had the influenza.

It was some little time before Lady Wychwood was able to bring her to reason, and a great deal of tact was necessary; but she managed it at last, and without wounding Miss Farlow’s sensibilities. She said that she did not know how she and Nurse were to go on, if Maria felt she must devote herself to Annis. That was quite enough. Miss Farlow, in a gush of affection, said that she was ready to do anything in the world to ease the burdens under which she knew well dear, dear Lady Wychwood was labouring, and went off, happy in the knowledge that her services were indispensable.

Unlike Tom, or Miss Farlow, Miss Wychwood was a very good patient. She obeyed the doctor’s directions, swallowed the nastiest of drugs without protest; made few demands, and still fewer complaints; and resolutely refrained from tossing and turning in what she knew to be an unavailing attempt to get into a more comfortable position. As Dr Tidmarsh had prophesied, her fever mounted, and though it was too much to say that she became delirious, her mind did wander a little, and once she started out of an uneasy doze, exclaiming: “Oh, why doesn’t he come?” in an anguished voice; but she almost immediately came to herself, and after staring for a moment in bewilderment at Jurby’s face, bent over her, she murmured: “Oh, it’s you, Jurby! I thought—I must have been dreaming, I suppose.”

Jurby saw no reason to report this incident to Lady Wychwood.

The fever began to abate on the second day, but it still remained high enough to make Dr Tidmarsh shake his head; and it was not until the third day that it burnt itself out, and did not recur. Miss Wychwood emerged from this shattering attack so much exhausted that for the next twenty-four hours she had no energy to do more than swallow, with an effort, a little liquid nourishment, or to rouse herself to take more than a vague interest in whatever events were taking place in her household. For the most part of the day she slept, conscious of a feeling of profound relief that her bones were no longer being racked, and that the Catherine wheel in her head was no longer making her life hideous.

The fourth day saw the arrival in Camden Place of Sir Geoffrey. He had borne with equanimity the news, conveyed to him by his dutiful wife, that Miss Farlow was in bed with influenza; a second letter, informing him that Tom had caught the infection disturbed him a little, but not enough to make him disregard Amabel’s assurance that there was not the smallest need for him to be anxious; but the third letter (though she still begged him not to come to Bath), containing the news that Annis too had succumbed to the prevailing epidemic, set him on the road to Bath within an hour of his receiving it. He couldn’t remember any occasion since her childhood when Annis had contracted anything more serious than a slight cold in the head, and it seemed to him that if she could fall ill there was no saying when his Amabel would also be laid low.

Lady Wychwood received him with mixed feelings. On the one hand she was overjoyed to have his strong arms round her again; on the other, she could not help feeling that his presence in the house would be an added burden in an establishment already overburdened by three invalids, one of whom was the second housemaid. She was a devoted wife, but she knew well that he did not shine in a sickroom: in fact, he was more of a liability than an asset, for, enjoying excellent health himself, he had very little experience of illness, and either caused the invalid to suffer a relapse by talking in heartily invigorating tones; or (if warned that the invalid was extremely weak) by tiptoeing into the room, addressing the patient in an awed and hushed voice, and bearing all the appearance of a man who had come to take a last farewell of one past hope of recovery.

He was considerably relieved to find that his Amabel, instead of being on a bed of sickness, was looking remarkably well, but he could not like it that she had been tied to a cradle ever since Tom had developed influenza. He thought it extraordinary that there should be no one in the household able to look after a mere infant, and could not be convinced that Amabel was neither tired nor bored. She laughed at him, and said: “No, no, of course I’m not! Do you realize, my love, that it is the first time I have ever had Baby all to myself? Except for being unable to go to Tom, and being very anxious about Annis, I have enjoyed every minute, and shall be sorry to give her back to Nurse tomorrow. Dr Tidmarsh considers it to be perfectly safe now, but I am keeping Baby with me for one more night, for she is cutting another tooth, and is rather fretful, and I want Nurse to have a peaceful night before she takes charge of her again. You shall see Tom presently: he is laid down for his rest at the moment. Say something kind to Maria, won’t you? She has been most helpful, looking after Tom.”

“Yes, very well, but tell me about Annis! I was never more shocked in my life than when I read that she was in such very queer stirrups! I could hardly believe my eyes, for I don’t recall that I’ve ever known her to collapse before. It must have been a pretty violent catching?”

At this moment they were interrupted by Miss Susan Wychwood, who had been laid down to sleep on the sofa in the back drawing-room, and who now awoke, querulously demanding attention. Lady Wychwood glided into this half of the room, and was just about to pick Miss Susan up when Miss Farlow came hurrying in, and begged to be allowed to take the little darling. “For I saw Sir Geoffrey drive up, and so, of course, I knew he would wish to talk to you, which is why I have been on the listen, thinking that very likely Baby would wake—Oh, how do you do, Cousin Geoffrey? Such a happiness to have you with us again, though I feel you will be quite alarmed, when you see our dear Annis—if Jurby permits you to see her!” She gave vent to a shrill titter. “I daresay it will astonish you to know that Jurby has become the Queen of Camden Place: none of us dares to move hand or foot without her leave! Even I have not been permitted to see dear Annis until today! I promise you, I was excessively diverted, but I couldn’t help pitying poor Annis, compelled to accept the services of her abigail when those of a blood-relation would have been more acceptable. However I made no demur, because I knew that, tyrant though she is, I could depend upon Jurby to take almost as good care of her mistress as I should have done, besides that there was dear Lady Wychwood to be thought of, so worn-down as she was, which made me realize that her need of me was greater than Annis’s!”

She began to rock the infant in her arms, and Sir Geoffrey, who had listened to her with growing disfavour, beat a retreat, almost dragging his wife with him. As they mounted the stairs he said: “Upon my word, Amabel, I begin to wish I hadn’t prevailed upon Annis to engage that woman! But I don’t remember that she talked us silly when she and Annis have visited us!”

“No, dear, but at home you never saw very much of her. That is what I dislike about town-houses: however commodious they may be one can never get away from the other people living in the house! And goodnatured and obliging though poor Maria is I own I have frequently been forced to shut myself into my bedchamber to escape from her. I think,” she added reflectively, “if ever she came to live at Twynham I should give her a sitting-room of her own.”

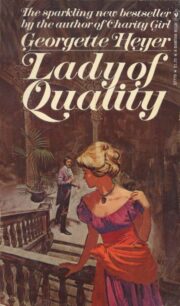

"Lady of Quality" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady of Quality". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady of Quality" друзьям в соцсетях.