Except there were no ordinary babies. Not in England, not on the Continent, not among the natives on any continent in any culture. There had never been an ordinary baby—not to the child’s mother, in any case.

“Miss Windham, I really must be going.”

That got her attention. She peered up at him, her expression disgruntled.

“Must you? Will you at least let me feed you before you go? The taverns and public houses will be full to the brim, and you have been quite kind to both Kit and me. I haven’t even offered you a decent cup of tea, so you really cannot be going just yet, Mr. Charpentier.”

She rose with the child, her hold on him as confident and relaxed as if this were her fifth baby. She was perhaps old enough to have had five babies—she wasn’t a girl by any means—but her figure belied the notion entirely.

Sophie Windham was blessed with a body a courtesan would envy. Devoid of cloaks and shawls and capes, Vim could assess her womanly charms all too easily.

“I appreciate the offer, Miss Windham, but the sooner I’m on my way, the sooner I’ll be able to find lodging with friends. Your offer is much appreciated nonetheless.” He reached for his greatcoat, still draped over a chair, but she advanced toward him, determination etched on her features.

“Sir, I am virtually alone in this house with a helpless child dependent on me for his every need. I have no idea how to feed him. I know not how or when to bathe him. I haven’t the first idea when his bedtime should be or what do with him upon waking. The least you can do is impart some knowledge to me before you go wandering the streets of Mayfair.”

The angle of her chin said she’d stop him bodily. Maternal instinct, whether firsthand or vicarious, was nothing a sane man sought to thwart.

“Perhaps just a cup of tea.”

“Nonsense.” She eyed him up and down. “You’ve likely had nothing to eat since dawn, and that was probably cold, lumpy porridge with neither butter nor honey nor even a smidgen of jam. Come along.”

He once again fell in step behind her, but this time he was free to admire the twitch of her skirts. If she wasn’t the housekeeper, she was likely a personal companion to the lady of the house. She had that much self-possession, and no woman her age would have been left unchaperoned by her family were she a member of the actual household.

“Have a seat,” she said, nodding at a plant table in the middle of the big kitchen. “I’ll put us together a tea tray, and you can tell me what Kit will eat.”

She was bustling around the kitchen with the particular one-handed efficiency parents of a very small child developed. The boy would be attached to her hip in a few days, or her back…

“Give me the baby.” He held up his arms and saw she was tempted to argue. “If you’re working around boiling water and hot stoves, he’s safer with me.”

She relented, handing him the baby then tucking the shawl more closely around the child. She hovered for a moment near Vim and the baby now cradled in his arms, then straightened. “If you’ll hold him, I can put together a bit more than a cup of tea.”

She took an apron down from a hook and tied it around her waist in practiced moves, which made for another piece of the puzzle of Sophie Windham: a lady’s maid would never condescend to kitchen work, though in the absence of the cook, a housekeeper might.

“Has the family closed the house up for the holidays then?” He rubbed Kit’s back, not for the child’s comfort—the little shoat was fast asleep—but for his own.

“They went down to Kent early this year and gave most of the staff leave. Higgins and Merriweather will bide over the carriage house to keep an eye on the stock, and they’ll bring up more coal from the cellar if I ask it of them. Would you like an omelet? There’s a fine cheddar in the pantry, and the spice rack is freshly stocked.”

He needed to be going, true, but negotiating the weather on an empty stomach would be foolish. “An omelet sounds wonderful, but don’t go to any trouble.”

She smiled at him as she bustled into the pantry. “I like to cook, though this is a closely guarded secret. What should I be feeding Kit?”

“Bland foods, of course. Porridge with a bit of butter and a dash of sugar, though my nurse always said honey wasn’t good for babies. Mashed potatoes with a touch of butter. Boiled vegetables, plain oatmeal.”

“What about meat?”

He cast back over more than two decades of memory. “Not yet, and not much fruit, either. Strawberries gave my youngest sister hives when she was a baby, so I wouldn’t advise them. Pudding was always very popular in the nursery.”

“If the weather weren’t so foul, I’d send one of the grooms over to fetch Nanny Fran from Westhaven’s townhouse. Do you like onions in your omelet?”

“A few.”

The kitchen was soon full of the scent of good, simple cooking. He watched as Miss Windham cut slices from a fresh loaf of bread then slipped them onto a tray for toasting. She moved with a competence that spoke of time served in the kitchen, and yet she could not possibly be the cook: if the entire household had been given leave, there was no point in the cook remaining for just two grooms.

“Where do you hail from, Mr. Charpentier?”

“Here and there. The family seat is in Kent, though I was raised at my stepfather’s holding in Cumbria. I’m a merchant by profession, trading mostly with the Americans and the Scandinavians these days.”

“I’ve never seen Cumbria, though I’m told it’s lovely.” She spoke as she worked, the epitome of domestic tranquility.

“Cumbria’s lovely in summer. Winter can be another matter altogether.”

“Will you be with family for the holidays?”

He was distracted momentarily from answering by the picture she made standing at the stove, watching the omelet cook as she occasionally peeked at the toast and also assembled the accoutrements of a tea tray.

Why wasn’t she with family? He barely knew the woman, but seeing her here, cooking for him, making him feel welcome with small talk and chatter while the snow came down in torrents outside, he felt a stab of something… poignant, sentimental.

Something lonely?

“I’ll be with my uncle and his family. I have half siblings, but my sisters have seen fit to get married recently, and one doesn’t want to impose on the newlyweds.”

“One does not. Three of my brothers have married, and it can leave a sister not knowing quite how to go on with them. Pepper?”

“A touch.”

“Is he asleep?”

“Never ask. If he is, it will wake him up. If he isn’t, it will let him know you’re fixed on that goal, and he’ll thwart you to uphold the honor of babies the world over.”

She smiled at the omelet as she neatly turned it in the skillet. “Her Grace raised ten children in this house. She would likely agree with you.”

A ducal household? No wonder even the domestics carried themselves with a certain confidence.

When he might have asked which duke’s hospitality he was imposing on—his half brother had regular truck with titles of all sorts—she brought the tea tray to the table, then cutlery and a steaming plate of eggs and bacon. She set the latter before him and stood back, hands on hips.

“If you’ll give me the baby, I can hold him while you eat.”

“And what about you? As a gentleman…” But she was already extricating the child from his arms and taking a seat on the bench along the opposite side of the table.

“Eat, Mr. Charpentier. The food will only get cold while we argue.”

He ate. He ate in part because a gentleman never argued with a lady and in part because he was starving. She’d served him a sizeable portion, and he was halfway through the omelet, bacon, and toast when he looked up to see her regarding him from across the table.

“You were hungry.”

“You are a good cook. Is that oregano in the eggs?”

“A little of this and that.”

He paused and put his fork down. “A secret family recipe, Miss Windham?”

She just smiled and pretended to tuck the shawl around the sleeping baby; then her brow knit. “Earlier today you mentioned a Portmaine family secret. Is this your wife’s family?”

It was a logical question. It could not possibly be that this brisk, prim woman was inquiring as to his marital status. “My mother remarried when my father died. Portmaine was my stepfather’s family name. It is not my good fortune to be married.”

She nodded, and Vim went back to devouring the only decent food he’d had in almost a week of traveling. Yes, he could have taken the traveling coach from Blessings, but Blessings and all its appurtenances belonged to his younger half brother, who might have need of the traveling coach himself.

So Vim hadn’t asked. He’d taken himself off, traveling as he often did among the common folk of the land.

“Did you ever want to marry, Mr. Charpentier?”

He looked across the table at Miss Windham to see she was again pretending to fuss with the baby, but a slight blush on her cheek told him he’d heard her question aright.

“I always expected to marry,” he said slowly. His uncle certainly expected him to marry—ten or twelve years ago would have suited the old man nicely. “I suppose I haven’t met the right lady. You?”

“What girl doesn’t expect to marry? There was a time when my fondest wish was to marry and have a family of my own. Not a very original wish, I’m afraid.” She shifted the baby and reached across the table to pour them each a cup of tea. As long as she’d let it steep, Vim could smell the pungent fragrance of the steam curling up from his cup.

“Darjeeling?”

“One of my brothers favors it. How do you take your tea, Mr. Charpentier?”

“My friends call me Vim, and I will be fixing the tea for you, Miss Windham, seeing as your friend is yet asleep in your arms.”

She frowned, but it was a thoughtful expression, not disapproving. “My friends call me Sophie, and my siblings do. You may call me that if you like.”

It wasn’t a good idea, this exchange of Christian names. Watching some subtle emotion play across Miss Windham’s—Sophie’s—face, Vim had the sense she allowed few to address her so familiarly. He wouldn’t have made the gesture if he weren’t soon to be leaving, never to see this good lady again.

“Sophie, then. Miss Sophie. Will you eat now? I can hold Kit.”

“You’re sure you’ve had enough?”

“I have eaten every crumb, so yes.” He rose and came around the table, reaching down to retrieve the baby. She didn’t hand him up, though, so when Vim reached for the child, his arm extended a little too far, to the point where his hand slid a few inches down Miss Windham’s breastbone before he could get a decent grip on the child.

Down her breastbone and along the side of one full breast.

The contact lasted not even a second and involved the back of his hand and her bodice, nothing more, but Vim had to work to keep the frisson of lust that shot through him from showing on his face—a moment of sexual awareness as surprising as it was intense.

The lady, for her part, took a sip of her tea, looking not the least discomposed.

“Best eat quickly,” Vim said, settling the child in his arms. “You never know when My Lord Baby will rouse, and then the needs of everyone else can go hang. It was a very good omelet.”

“Is there such a thing as a bad omelet?” She ate daintily but steadily, not even glancing up at him while she spoke.

“Yes, there is, but we won’t discuss it further while you eat.” He resumed his seat across from her, the weight of the baby a warm comfort against his middle. Avis and Alex could both be carrying already, a thought that sent another pang of that unnameable sentiment through him.

“What else can you tell me about caring for Kit, Mr. Char—” She paused and smiled slightly. “Vim. What else can you tell me, Vim?”

“I can tell you it’s fairly simple, Miss Sophie: you feed him when he’s hungry, change him when he’s wet, and cuddle him when he’s fretful.”

She set down her utensils and gazed at the baby. “But how do you tell the difference between hungry and fretful?”

Her expression was so earnest, Vim had to smile. “You cuddle him, and if his fussing subsides, then he wasn’t hungry, he was just lonely. If he keeps fussing, you offer him some nourishment, and so on. He’ll tell you what’s amiss.”

“But that other business, at the coaching inn. You knew he was uncomfortable, and to me it wasn’t in the least obvious what the trouble was.”

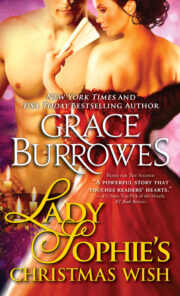

"Lady Sophie’s Christmas Wish" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Sophie’s Christmas Wish". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Sophie’s Christmas Wish" друзьям в соцсетях.