“I must hope, then, that Miss deCourcy’s disposition is a generous one.”

“Have you never met her?”

“No, never. The news of Charles’s engagement took Sir Frederick and me quite by surprise. Charles has been a bachelor for so many years that we had concluded he was content to be so. He had never mentioned any acquaintance with Miss deCourcy at all until after the engagement had been formed.”

The visit did not last long beyond this exchange, and when Mrs. Johnson next spoke to Eliza Manwaring, she repeated it with blithe inaccuracy, and Mrs. Manwaring did not hesitate to add embellishments of her own when she conveyed it, and soon it was all around London that Lady Vernon disapproved of her brother-in-law’s union with Miss deCourcy, that she had likely expected Charles Vernon to pine away for her forever, and that she was the worst sort of hardened coquette, who could bear for no one to be admired but herself.

chapter six

The marriage of Charles Vernon to Catherine deCourcy was celebrated in so exclusive a fashion that among those excluded were the groom’s own brother and sister-in-law. Charles Vernon wrote to Sir Frederick, explaining that the ceremony was to be held very near the deCourcy estate and that the indifferent health of Sir Reginald would not allow for much company and commotion. Sir Frederick was sorry to miss the ceremony, as weddings were such happy gatherings, but he wrote to his brother offering kind congratulations, and Lady Vernon likewise dispatched her very best wishes to her new sister-in-law. The replies they received were civil and completely lacking in warmth, for Miss deCourcy had been informed by her mother, who had heard from her husband’s sister, Lady Hamilton, who had been told by Lady Millbanke, who had it on very good authority from Eliza Manwaring that Lady Vernon was said to have heard something so ill of Catherine deCourcy as to make her positively set against Charles Vernon’s marriage.

As for Charles Vernon, he had got a handsome dowry, a position in a banking establishment, and a wife. Another man would have been contented, but Charles was of a temperament that dwelt less upon what he had attained than what he had been denied. An alliance with one of the oldest families in England did not do away with the knowledge that his first choice had preferred his brother, and a position with a respectable establishment only served to remind him that he was obliged to do something to keep himself, while Frederick had to do nothing at all. But what rankled most was the fact that Frederick would not sell Vernon Castle for what Charles was willing to pay, which left him unable to purchase an establishment of his own, as he had been compelled to apply the greater part of his wife’s dowry toward reconciling his debts. He and his bride, therefore, had no alternative but to settle in Parklands Cottage on the deCourcy estate.

Parklands Cottage was far less humble than the term cottage generally implied. The residence was modern and roomy and the gardens and copses were so cunningly laid out as to almost make one forget that it was only separated from the great house by a quarter-mile lane. Unfortunately, Charles Vernon could not forget it. Mrs. Vernon felt herself obliged to visit her parents every day, and these visits often concluded with Lady deCourcy walking back to the cottage with her daughter and staying to tea. Visitors to Parklands were rare, and there was no sport at all, as Sir Reginald’s frail health would not permit the commotion. They dined with fewer than half a dozen families, people who had no conversation and little interest in anything beyond the neighborhood. Charles was not long married when he was persuaded that if he could put a greater distance between his wife and her parents, he might almost be willing to sacrifice one or two of his private vices to accomplish it.

A situation in the banking house had the material advantage of taking him often to town. There, in the livelier society of gentlemen who had amassed fortunes in India or Antigua, or who had been the happy beneficiary of a relation’s premature demise, and free from the scrutiny of his wife and her mother, Charles gave way to indulgence. When these visits concluded, he would return to Parklands less contented and more in debt than when he had left it, and he would half resolve to live frugally. But whenever a surplus of money came his way, it was spent.

In due course, they were blessed with a young Charles, who was followed by Frederick, Kitty, and Regina. With each addition to her family, Mrs. Vernon was more content to remain as they were, while Vernon became impatient for change, an impatience that had him always eager to accept his affectionate brother’s invitations to visit Churchill Manor. Mrs. Vernon, persuaded as she was that Lady Vernon had opposed her marriage, would never consent to going, but her mother had advised that a gentleman must have some diversion, and Churchill was a better bargain than London, where Charles was wont to spend too freely.

And yet Vernon’s visits to his brother were not entirely without cost, for they had a very adverse effect upon his equanimity and contentment. The family property, which in his youth Vernon had found to be very dull and insignificant, had become one to be coveted. Vernon did not consider how far Sir Frederick’s affability and Lady Vernon’s refinement and taste had effected Churchill Manor’s rehabilitation. He saw only that there it was all liveliness, elegance, and good company, which was a sharp contrast to the dull routine of Parklands Cottage and the insipidity of the deCourcy family circle.

Inevitably, Charles Vernon would come away from Churchill Manor, dwelling upon the accident of birth that had given Sir Frederick precedence, and lament, “What an excellent thing it is to have an estate of one’s own! Why would they not sell Vernon Castle to us! How well situated we should have been if I had been the elder!”

His wife did not share his feeling; she longed for no change in circumstance, as there would be no other situation where she might be both a pampered daughter and a complacent wife. “We must not be downcast, my dear, but look to the future and hope for the best. Sir Frederick is already past forty, and he cannot live forever. We will have Churchill Manor in time, or our son shall.”

Charles could not be encouraged by the latter prospect, as it could not take place until his own demise, and soon all of his waking hours were entirely consumed with schemes and contrivances directed toward improving his situation—imaginings that, more often than not, were reliant upon Sir Frederick being put in his grave.

chapter seven

In Frederica’s fifteenth year, a spell of excellent weather persuaded Sir Frederick to bring together a small hunting party to Churchill Manor after Michaelmas. A matter of business kept Sir James Martin at Ealing Park, and as there were no other single gentlemen in the party, many of the marriageable ladies and their mothers had stayed at home as well. On a morning that was too damp for the ladies to take exercise out of doors, Lady Vernon sat with Eliza Manwaring and Frederica’s governess, Miss Wilson, in the parlor that overlooked the hedgerows and lawns.

“Maria and I enjoyed our month at Bath so much that we may do it again in the coming year,” Mrs. Manwaring remarked. “I recommend it for Miss Vernon, as there were a great many plants and grasses that grow nowhere but in that climate. And the public rooms are filled with a very lively set of young people. I think she would like it far better than London.”

“I think that she would like to stay here in the country better than either of them, but we must bring Frederica to town for the season,” replied Lady Vernon. “She has been to London only once, and my Aunt Martin means to come down on purpose to see Frederica presented at court.”

“Well, you must not have any great expectations for her first season, and if nothing comes of it, you will have time for a few weeks at Bath. I am certain that Mr. Lewis deCourcy will be happy to have you come, particularly now that there is a family connection that brings you even closer.”

“My fondness for Mr. deCourcy cannot be improved upon. I will always be grateful to him for his many kindnesses to my father.”

“He is truly the gentleman, to be sure, and quite distinguished looking for a man of his age. His nephew must resemble him, for it is said that Sir Reginald is quite frail and sickly. Have you met Mrs. Vernon’s brother?”

“Mr. Reginald deCourcy? Why, no. Do you know him?”

“We very nearly met him at Bath,” said Eliza. “He was at an assembly with our mutual acquaintance Mr. Charles Smith—a very high-spirited, forward sort of young man. I had hoped that he would introduce us, but Mr. Reginald deCourcy did not seem inclined toward talking much to anybody, and he did not stay above an hour, though Mr. Smith remained until the very last.”

“And what is Mr. deCourcy like?”

“He is certainly a handsome fellow, tall and a bit imposing in his bearing and countenance, but I suppose he has every reason to think well of himself, for there are few young men in England who will come into a better fortune. Try as we might, we did not see Mr. deCourcy again before we left Bath. Mr. Smith told us that his friend spent nearly all of his time at the library and declared that Mr. deCourcy was a very dull fellow, though I am certain that he exaggerates, for Charles Smith is the sort who always takes it upon himself to amend the truth.”

“Then perhaps in amending Mr. deCourcy’s character, he improves it, and in truth Mr. deCourcy is much duller than his friend reports.”

Eliza was about to make her reply when Frederica flew into the room with her hair disheveled and her apron strings flying loose. “Mama! Come at once! Father has been injured!”

Miss Wilson threw aside her needlework and rang the bell while Lady Vernon and Frederica dashed out of the house and tumbled down the sloping meadow to the wood. The two women had just reached the trees when they were met by a party of men who were carrying the senseless Sir Frederick. His forehead and one forearm were wounded and bleeding.

“Good God, what has happened to him!” Lady Vernon cried in great distress.

“I found him on the ground with his boot caught in a large tree root,” Charles Vernon stammered. “It must have tripped him up, and he struck his head when he fell.”

Lady Vernon took command at once and ordered one of the men to send for the surgeon while Sir Frederick was carried to his chamber. She then called for water and bandages, and with the assistance of her daughter and her maid, dressed her husband’s wounds while the others paced and asked each other if there was something more to be done.

The surgeon arrived, examined the patient, and praised Lady Vernon for her skill, declaring, “You must summon me at once if he regains consciousness, but until that time, you can only make him as comfortable as possible.” He then departed with a promise to return that evening.

Lady Vernon remained at her husband’s side, leaving Miss Wilson and Deane to perform her offices. Mrs. Manwaring suggested that a house full of company would only add to Lady Vernon’s burden and advised that they make preparations to depart. Manwaring argued against his wife’s proposal—they must remain, he was certain that Sir Frederick would wish them to remain—but the rest of the party was of the mind that they must defer to Sir Frederick’s brother, and Charles Vernon seemed very eager to have them go.

His presence proved to be more of a trial than a relief to Lady Vernon. His excessive agitation did nothing to promote an atmosphere of confidence and calm, and his attempts to take Frederica’s place at her father’s bedside were so persistent that they were an irritation rather than a comfort. Lady Vernon rebuffed him with as much civility as she could, but she could spare little attention for anyone but her husband.

Frederica would not yield her place to her uncle, but when Sir Frederick appeared to be sleeping comfortably, she slipped into his dressing room and, taking up a sheet of paper and pen, she wrote to Sir James.

Miss Vernon to Sir James Martin

Churchill Manor, Sussex

My dear cousin,

I would not trouble you when the business that has kept you from coming to us must be pressing, but a terrible situation has risen that compels me to beg for your immediate assistance. My father has been gravely injured and I know that my mother would be grateful for your counsel. She cannot leave my father’s bedside, or she would write to you herself.

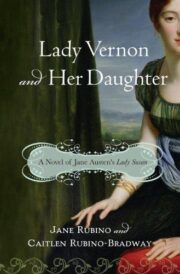

"Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" друзьям в соцсетях.