"Wait until you hear what I saw tonight," Laura said, pleased to have them home at last. "I’ll put on the teakettle so we can talk."

"Wonderful, Laura," Sarah said, unclasping her cape and draping it over the clothes tree in the hall.

Leading the way into the kitchen, Laura excitedly talked about the women and police in Washington Circle. She could feel her blood rise as the replayed scene created a flurry of images in her mind.

Sipping her tea, she ended the story in a low, emotion-charged voice. "It was terrible, the way the police herded the suffragists into the van as if they were cattle. No one should be treated like that!" Laura glanced from her mother to Sarah, expecting to see horrified expressions, but they remained impassive. Her voice rose a notch. "The women hadn’t done a thing! All they want is the right to vote. We need to help them!"

At these words her mother stirred her tea faster and frowned slightly. "Laura, don’t fly to their defense so easily. These women are zealous over a cause that should wait. Right now they should use their energy for the war effort."

Laura gazed at her in disbelief. Was this the Maude Mitchell who was noted for her civic work ? Was this the Maude Mitchell who was noted for her strong-mindedness? How could her mother condemn the suffragists' cause?

Maude reached over, patted her daughter’s hand, and offered an explanation. "Yes, someday I want the vote, too, but until the Germans surrender, there are more important issues to consider."

Laura couldn’t swallow away the disappointment she felt. She turned to Sarah, but her sister studied Laura with troubled blue eyes and shook her head. "You mustn’t think of becoming involved in a group that provokes such violence. I agree with Mother."

Laura carefully set down her cup. "When don’t you?" she murmured, miserable at Sarah’s lack of sympathy.

Sarah gave her a sharp look; that is, as sharp a look as she could muster. Sarah seldom frowned or criticized and always tried to find something positive to say, which annoyed Laura no end. Laura observed her older sister’s plump, round face with its rosy cheeks and cherubic smile. Sarah’s blonde, waved hair, short and stylishly cut, her crisp, white blouse so carefully ironed, all were signs of her meticulous nature. It was hard to imagine Sarah as a suffragist and carrying a placard, yet Laura had seen women just as well dressed in the fight tonight.

"Hmmm," her mother said, breaking the silence. "On such a cold night this tea tastes marvelous." She was adroit at changing the subject.

But Laura, pouring more boiling water into her cup, didn’t intend to be put off. "These women have as much backbone as a regiment of men. All they want is equality!" She glanced at Sarah. "That affects you, too, Sarah. You know very well that your factory job was held by a man for fifty cents an hour, and you’re doing the same work for only twenty-five cents. Doesn’t that make you angry?"

"I’m glad to do my part for the war," Sarah said calmly.

"Girls, please," Mrs. Mitchell said wearily.

"Well, why is Sarah so dense?" Laura inquired. "Why can’t she understand what I’m saying?"

"Laura," Sarah said in her best older sister voice. "There’s nothing more important right now than winning the war."

"It’s not as if these women are plotting to blow up the White House! And they aren’t interfering with the war effort, either," Laura snapped. She gulped her tea and glared at Sarah.

The two sisters gave each other a long look. Then Sarah said, condescendingly, "I declare, Laura, you’d defend Mata Hari if she were alive today."

Mata Hari! Laura bridled at Sarah’s words. The glamorous German spy who had been caught and executed by the French was hardly her idea of a heroine. Laura pressed her lips together and refused to dignify Sarah’s reproach with an answer. But she silently vowed to read every word of the pamphlets she had brought home.

Maude Mitchell rose, turned, and set her teacup on the countertop. "I’m going to bed." She kissed the top of her daughters' heads.

"Mother, I’m so tired of Sarah’s prim and proper attitude," Laura said defensively, trying to reason with her mother, so that she’d see that Sarah wasn’t always right.

Her mother sighed. "Please don’t argue anymore."

"But, Mother," Laura began, then stopped. Maude Mitchell looked so tired. The dark circles under her eyes meant she was worried and not sleeping well. Laura knew it was because she was deeply concerned about Michael, since they had not heard from him in weeks. "All right, Mother," she agreed. "No more arguments." She managed a small smile.

However, after Mrs. Mitchell left, Laura glared at Sarah. "You’re living in the wrong century, Sarah. Don’t you realize it’s 1918, not 1818?

Sarah’s little laugh tinkled throughout the kitchen. "Your freckles are dancing right off the tip of your nose!"

Laura couldn’t help grinning. Her affection for Sarah was always there, no matter how much their views differed. Despite the fact that Sarah was nineteen, only four years her senior, she might as well have been forty. Instinctively her sister always did the correct thing. Well, that was fine for Sarah but not for her. There were just some ideas you had to respect and stand up for. Impulsively she reached over and squeezed Sarah’s hand. "I didn’t mean to snap at you."

"I know you didn’t." Sarah touched Laura’s cheek with her hand. "You look tired, Laura. Your motorcade drill must have been strenuous today. Why don’t you go to bed?"

"If you will, I will," Laura retorted smartly.

"I’ll be right there. Just as soon as I put out the bottles for the milkman."

"Good night, dear Sarah," she said in mocking affection. She gave her a quick hug, turned, and ran upstairs.

As she turned down her bed she could hear the Menottis' record player above her. No doubt Joe had come home from work.

Slipping off her camisole, she paused and listened to the strains of the song, "Over There." The stirring refrain made everyone a patriot. As the tune permeated the wall she softly sang, "Over there, over there…."

Her fight with Sarah was forgotten as she thought of a line from the song: "The Yanks are coming." Her brother was a Yank who had gone over there. When the Germans saw the number of Americans pouring into France, she thought, perhaps they’d surrender.

She flung her robe across the bed. If only the war would end and Michael would come back to his job at the American Institute of Architects. He was respected for his creative designs, and it was little wonder that he’d won awards, for he’d had the best teachers in the world. He had studied under Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., the famous city planner whose designs even now were making sweeping changes throughout the city. Her father had helped him, too. Like father, like son, she mused. Her heart lurched at the memory of her dad. He, too, had been a famous architect, until his heart attack two years before.

When he had died, Laura had lost a portion of herself. For a year she had moped in her room, losing herself in the fantasy world of books. How she had missed him! She could still hear his booming laugh, see his black beard and impish eyes. He had believed in her and promised that she, too, should become an architect. He had been so proud of her designs, and she had kept them under her bed until his death. Then, one night, she took them out in the backyard and burned each one, watching the blueprints catch fire, curl up, and become ashes. She would never become an architect. One in the family was enough.

Now she had no idea what she wanted to do. Her father had told her she could become anything she wanted to. She had brains and energy, and just because she was a girl didn’t mean a thing. "Do you want to be a doctor? Lawyer? Indian chief? You can!" he had said firmly.

A tear slipped down her cheek. She would never forget him, but she thought she was all through with tears. She sniffled. She had adored him. He had called her "his Sun Ray" because she was such a bright and warm daughter. She blew her nose and smiled at the picture of them dancing together on her thirteenth birthday. He had waltzed her around the parlor, not only because it was her birthday, but also because she had brought home a report card of straight As. Now, however, she had no one who had such a deep faith in her. Her mother loved her and believed in her, but her mother’s horizons were more limited than her father’s had been.

In a fury she stood before the mirror and touched her toes twenty-five times. A few more exercises and she jumped in bed and slipped down beneath the quilt, reaching for a pamphlet — anything to take her mind off the past.

She began to read about the women’s movement and Miss Alice Paul, the leader of the National Women’s Organization. Miss Paul, who had come over from England to help her American sisters get the right to vote, had been arrested last June and kept in prison for seven months. She had been released only last month. One of the women with her described their ordeal and how they had been force-fed with tubes up their noses. Laura shuddered at the graphic description. How could these ugly things happen in a free United States? She continued to read about the history of the movement and the way it had started in the early 1800s, but she was too sleepy to continue. She reached over, switched off the light, and snuggled beneath the covers, thankful she was in a soft bed rather than on a prison cot.

Abruptly the record player stopped. Was Joe getting ready for bed, too? She could hear his footsteps moving back and forth. Darling Joe! Little did he know what future plans she had in store for him. She stared into the dark for a long time. Maybe tomorrow night at the movies he would notice her, but she knew there was not much chance that this Friday would be any different from last Friday. She sighed and rolled over, punching the pillow. What a farfetched dream — to think Joe would see her as a grown-up overnight. She curled up and closed her eyes, hoping to dream of Joe, but when she slept, instead of sweet dreams she had nightmares of running, screaming women.

Chapter Four

The next morning when the alarm sounded, Laura groaned and pulled the blankets over her head. Six o’clock, Friday morning, the last day of school before the weekend. She didn’t know if she could face Mr. Blair this morning. Obviously her views baffled and frustrated him, and she, in turn, could not fathom his attitude.

Reluctantly she threw back the quilt and dashed into the bathroom, filling the sink with water and splashing her sleepy eyes awake.

She dressed quickly, but fastening the cuff links on her starched striped blouse and buttoning the high collar slowed her. "Devils and hobgoblins," she muttered as she hooked up the side of her full skirt.

Next she used the buttonhook to fasten her high-buttoned shoes and was finally ready, except for catching her thick curls with a large black taffeta ribbon, which stood out at the nape of her neck like two miniature bat wings.

She hurried to the kitchen where she cut a slice of bread, drank a cup of black coffee, and listened to the house’s silence. Her mother and Sarah had left for work, the Menottis were at their grocery store, and the only sound was the swish, swish of Otto’s broom. What would they do without Otto Detler, she thought, scraping the dishes before washing them. Since her father had died and left them this house, they had worked very hard to maintain it. Otto had lived in the basement apartment for twenty years. He was not only an excellent tenant but also a fine handyman, and he took as much pride in their eighty-year-old house as they did. Otto had come from Hamburg, Germany, and though his English could be understood, he still spoke with a heavy accent.

It was not easy to keep the house and yard immaculate, but they managed. Her father had designed the back porch and helped plan the landscaped, terraced backyard with the two large elms and the array of flowers along the fence. The trees were bare now, but in the spring all the blossoms throughout Washington would be wonderful to see. This whole house was a source of pride, but it was also back-breaking work.

Now, of course, they no longer had the flower garden, for it was replaced by a vegetable patch, a "Victory Garden." It was more evidence of the war effort. She glanced about the large but cozy kitchen with such bright touches as the yellow canisters, the red bowl holding fresh fruit, and the green rug. She knew little of the history of this house and enjoyed thinking of who had once occupied 314 Cherry Alley.

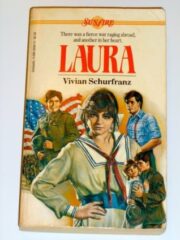

"Laura" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Laura". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Laura" друзьям в соцсетях.