She laughed, only a little bit too high, only slightly breathless. “But I warn you, I pull hair. Ask any of the girls on my street.”

“I should have known,” said Stephen, and applied completely unnecessary vigor to the final chair.

Then came candles, easily acquired from the kitchen, and the small silver cup that Stephen took out of a locked drawer. When he unwrapped it from its covering of green silk, Mina whistled.

“What’s this, then, the Holy Grail?”

“I shouldn’t think so,” said Stephen. “I saw it being made, and I’m nowhere near so old as all that.”

He had been very young at the time. It was one of his first memories: the glowing heat of the forge, the shine of fire from the half-made bowl, and his sister Judith’s eyes reflected in it, her hands almost as steady as his uncle’s. He’d known enough not to touch anything, and that had been about the limit of it.

“We have older ones,” he said, “elsewhere. But even metal wears after enough time. And then there were so many of us, and we took to wandering—it was better to have more than a few such objects.”

“Oh,” said Mina, round-eyed again. “It’s magic too, then?”

“Not so greatly as the crown, not of itself. It’s a tool. But I daresay magic clings to it somewhat after enough use.”

“Things start to be part of each other,” Mina said, half quoting Stephen.

The quickness of her reply, and the simple fact that she’d remembered, no longer surprised Stephen. They still made him smile. “Hold on to it,” he said, “while I pour the wine.”

He turned toward one of the bookshelves, taking with him the sight of her: mortal hands clasped around the stem of the goblet, mortal eyes reflected in its polished surface.

Things start to be part of each other, he heard her say again.

Nineteen

Wine came from the same drawer that had held the cup. The bottle was crystal, heavy-looking, and cut so that it threw off rainbows even in the dim light of the library. The wine was deep red, like the garnets in a bracelet Professor Carter kept in his study. From King Alfred’s time, a thousand years ago or more, he’d said when Mina had stared at it and forgotten to be professional.

The bottle was probably newer than that, at least, and no wine could have survived so long. And Stephen had said that the goblet was younger than he was—whatever that meant.

Marveling at the bracelet and Professor Carter’s other relics, reading his notes as she typed them, she’d sometimes almost felt time as a tangible thing, as if she could glimpse the past across a broad river. Now she felt that she stood on a shore and looked across the ocean, glimpsing, on some far island, the sun shining off a roof and knowing the breadth of the sea all the more intensely for that vision of the other side.

“How old was your father?” she asked.

Stephen paused, wine bottle in hand. “When he died?” His accent was thicker than normal. “Perhaps four hundred years. We stop keepin’ score after a while, ye ken.”

Four hundred years. Stephen was perhaps half that, if Culloden was when Mina thought it was. And she was somewhat shy of thirty.

“You’re middle-aged, then?” she asked and tried to smile with it.

He shrugged, and this time, there was a more-than-human grace to the movement, a suggestion of rippling muscles even through his clothes. His smile was broader than usual too, and his teeth looked sharper.

“I suppose you could be saying something of the kind. It’s no’ so direct a comparison, though. We dinna’ spend fifty years as spotty youths.”

“Fate worse than death, I’d think,” said Mina and laughed, which took the worst of the edge off. Not much more than that, though. The library was large, dark, and old. Even against the size of it, Stephen loomed above her.

She pressed her hands hard against the goblet and straightened her back, bringing herself to an almost military posture. “Right, then. What do I do?”

“Hold the cup out,” said Stephen.

His voice was deep in her ears, and his eyes, meeting hers, were bright gold again. Mina’s arms moved almost on their own, slowly and fluidly. She watched the wine flow from crystal to silver, bottle to chalice, and her mind went with it—flowing, rippling, then still.

Close at hand—how had he gotten so close without her noticing? And when had he put down the bottle?—Stephen took a sudden deep breath and looked down at her with lifted eyebrows and a startled quirk of his mouth.

“Is something wrong?”

It was her voice, only it came from far away and high up.

“No. No.” Stephen reached out, but stopped with his hand a few inches from Mina’s hair and smiled at her instead. His teeth still looked very sharp, but the smile was warm nonetheless. “Worry not, Cerberus. This comes easier to you than I’d thought it would. That’s all.”

“Oh,” she said. She’d have had a sharper answer if her mind had been where it normally was. Wit seemed distant now. So did worry: thank God, because she’d have been scared stiff otherwise. Runaway chariots of the sun came to mind, and hand mills that wouldn’t stop making salt. “You’ve done this a few times, then?”

“A few,” said Stephen.

For her own peace of mind, Mina decided not to press for more details. “What do I do?” she asked.

“Follow me. You’ll not have to say anything. Just hold the goblet and move as I do.” He did touch her cheek then. His fingers were almost hot enough to burn, but Mina turned her face toward them anyhow. The sensation was not quite painful. “Ready?”

“I’m ready.”

They went slowly in a circle that felt much larger than it really could have been.

In her mind, overlaid on the image of the wine-filled chalice, Mina saw the house as if from a great height. She saw the gardens leading up to the gate; she saw the small stable behind it; she saw the tradesmen’s entrance and the polished front steps. She saw the walls, sturdy and stone, and then, rising up within them, she saw another set of walls. This one was translucent and shone, patterned like stained glass with intertwining ladders of color: red and gold, brown and blue.

The first set of colors was Stephen; the second was her.

Joy followed the image, sudden and unbidden and inexplicable. What she looked on was beautiful in a way that she’d never imagined and couldn’t fully understand. The light that poured through those magical barriers, or out of them—the house itself, and the people who moved in and around it—the very pace of their walking and Stephen’s speech all took her breath away. Still from a great distance, Mina knew that her cheeks were wet with tears.

Later, she’d be embarrassed. Now there was no room for such emotion. There was only wonder and the need to see the ritual through.

She followed, listened, and watched as the walls came up and grew solid, watched in wonder until Stephen’s hand on her shoulder brought her halfway back to herself, dizzy and blinking.

“Oh,” she said again. Stephen’s face was close to hers. She met his eyes, and he took another quick, startled breath. Then he brushed his fingertips under each of her eyes, wiping the tears away.

“Silly of me,” she said and stepped back, her face feeling almost as hot as his fingers.

Stephen shook his head. “Furthest thing from it,” he said gently. “Forgive me. I should have remembered.”

“What—why—” The words for what Mina wanted to ask didn’t come. Maybe it was because she didn’t need to ask the first questions that came to mind. She knew why she’d been crying. It had been for beauty and joy; more than that, it had been for the certainty that there was more to the world than she’d suspected, and the knowledge of her own part in that greater whole. She’d seen a power that even she could grasp and use, as common and mortal as she was.

She settled for asking, “Remembered?”

“Magic—at least magic this complicated—has a way of overpowering you when you’re new to it.”

“Haven’t been that in a while, have you?” Mina asked and felt some of her wonder die away even as she said the words.

“Not in some time.”

There was nothing surprising in that. The knowledge settled into her chest, a hard little lump like a gemstone—and, considered sensibly, just as valuable. He was not mortal. He was not human. The more Mina had to face that, the better for everyone.

The sooner all of this was over, the better for everyone.

She smoothed her hair back and blinked the rest of the tears out of her eyes. “You should go lie down,” Mina said, putting her old brisk self on again. “You’ve taxed yourself quite enough for your first day on the mend. And I have work to do.”

Twenty

Sleep came quickly, lasted long, and because there was some benevolence to the universe, contained only darkness. When Stephen woke, it was almost sunset.

Immediately, he thought of Mina. She’d almost certainly already eaten and begun her day’s tasks—Stephen wouldn’t think of them as duties, since she’d taken them on herself—and the thought was a disappointing one. The one that followed was even less happy. Perhaps she preferred his absence. She’d certainly seemed eager enough for it the previous day.

It shouldn’t have mattered. She was mortal. A few months ago, she’d known nothing of the world beyond the obvious physical manifestations and would have laughed off any mention of magic as a tale for children. She hadn’t even been conceived when Stephen had made his trip to Bavaria. Yesterday and the day before had exposed Mina to a great deal. If she’d decided that she wanted no part of it—or of him—then the lass was showing good sense.

But he remembered the wonder in her face when she’d been casting the wards and the way her eyes had glimmered at the end.

He would have liked to see that expression on her face again.

“If wishes were horses,” Stephen said darkly to the empty room, and picked up the newspaper.

He didn’t read most of it. The political situation in France, the Queen’s latest speech, and the theatrical reviews brushed lightly past his consciousness. Trying to keep his mind off Mina, Stephen had to send it down other paths.

His health was one. Sleep had done some minor wonders for his lungs. He could breathe without pain now; more importantly, it would be safe to transform. Injury to the human form could cause…problems…if it was bad enough, and Stephen particularly wanted to be in full control that evening. He cleared his throat experimentally, felt no pain—and then froze, suddenly focusing on a column in the paper.

East End Slaughter, the headline read.

Below it, in smaller print: Men Butchered, and then Police Seek Killer.

An unsettling set of headlines, to be sure, but not one that would ordinarily have caught Stephen’s attention. London was a large city. Men had been killing each other for longer than he’d been alive.

Photographs were new.

One was of a lonely section of docks near a large warehouse. Someone had removed the bodies: no need to scare the ladies.

The other was older. One of the men had been in a police station before, brought up on charges of theft, and the officer there had been a forward-thinking man who took pictures of his charges. The picture was a few years old, and the paper didn’t reproduce it that well, but Stephen recognized the man nonetheless. It was Bill, the elder of the would-be thieves.

He would have wagered everything he owned that the other corpse was Fred.

When he went to tell Mina, she was in the library again, this time frowning assiduously at one of the larger and older books. Her ledger was open before her, and she had an uncapped pen in one hand. She looked up when the door opened but didn’t speak.

At first, Stephen couldn’t think of anything to say, either. In all his life, there had never been a good way to break the news of a death—and a death like this, with less pain in it than guilt, was even harder in its way.

He settled on bluntness. “I’m afraid I come with bad news,” he said. “I’m not completely sure, but it seems likely. You’ll recall the thieves?”

“I do,” said Mina. She put the cap on her pen and closed the ledger with a soft but decisive sound. “And I know. Told you I read the Times on my own, didn’t I?” she added. “Nasty business.”

“Yes,” said Stephen. He looked from her eyes to her hands. The former were calm and the latter still. Her voice was a little quieter than usual, a little less brash and challenging. That was all. “I hope you’re not—I hope it hasn’t been upsetting you.”

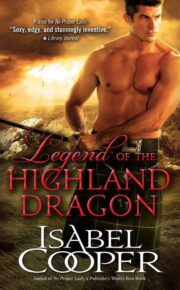

"Legend Of The Highland Dragon" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Legend Of The Highland Dragon". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Legend Of The Highland Dragon" друзьям в соцсетях.