Marianne felt as if she had been struck. Each word seemed to wound her to her very soul. She drew back, white to the lips, groping for Leopold Clary's arm and leaning on it heavily. Without that support she would probably have fallen in the dust that was already marking the red slippers of the prince of the Church. Those few words measured the gulf which had opened between her and her childhood days. She was seized by a sudden terror that, in his innocence and old-world chivalry, Clary would spring to her defence and utter the truth that she was that very opera singer in person. Marianne meant to tell her godfather the truth, the whole truth, but in her own time, not in the midst of a crowd.

Fighting desperately to control herself, she managed a pale smile, while her grip tightened on the Prince's sleeve.

'I will visit you tonight, if you will let me. Meanwhile, Prince Clary's carriage will take you home.'

The young Austrian stiffened.

'But – my dear, what will the Emperor say?'

At this she lost her temper, finding in her anger a release for her deepest emotions.

'You are not the Emperor's subject, my dear Prince. And may I remind you that your own sovereign is on excellent terms with the Holy Father. Or did I not understand you correctly?'

Leopold Clary drew himself up, as if in the presence of the Emperor Franz himself.

'You understood quite correctly. Eminence, my carriage and my servants are at your service. If you will do me the honour…'

Without turning, he clicked his fingers to summon the coachman. The carriage rolled obediently up to the little group and one of the grooms sprang down to open the door and let down the steps.

The cardinal's bright eyes took in the pale-faced girl in the blue dress and the Austrian prince, nearly as white as she in his white uniform. His clear gaze held a world of questions, but Gauthier de Chazay uttered none of them. Royally, he extended his hand with the great sapphire ring for Clary's lips to kiss, then turned to Marianne who sank to her knees, heedless of the dust.

'I will expect you this evening,' he said, as she rose. 'Ah, I was forgetting. His Holiness, Pius VII, has conferred a cardinal's hat on me. I am known, and admitted to France, by the name of San Lorenzo-fuori-muore.'

Moments later, the Austrian carriage passed the gateway of the Tuileries, followed by the envious gaze of the remaining princes of the Church who, one by one, were resigning themselves to departing homewards on foot, their followers at their heels, with the hope of finding a public vehicle for hire on the way. Marianne and Clary stood watching the Cardinal San Lorenzo out of sight.

Mechanically, Marianne dusted the silver embroideries of her dress with her gloves, then turned to her companion.

'Shall we go in?'

'Yes, although I wonder what our reception will be. Half the people in the palace saw us offer a carriage to a man whom the Emperor regards as his enemy.'

'You wonder too much, my friend. Let us go in and we shall see. There are many things in life, believe me, which are infinitely more to be feared than the Emperor's anger.' She spoke the words through clenched teeth, thinking of what her godfather would say that evening when he heard the truth.

The prospect threw a slight shadow over the joy which she had felt a little while before at seeing him again, but could not altogether destroy it. It was so good to find him, especially at a time when she had such urgent need of his help. What he would say would hardly be pleasant, she knew, he would not look kindly on her new career as a singer, but in the end he would surely understand. No one had more understanding and human sympathy than the Abbé de Chazay and why should the Cardinal San Lorenzo be any different? Marianne remembered suddenly how her godfather had always distrusted Lord Cranmere. He would surely pity the misfortunes of one who, as he himself had said a moment ago, was as dear to him as his own child.

No, all things considered, Marianne found herself looking forward to the evening with more hope than foreboding. Gauthier de Chazay, Cardinal San Lorenzo, would have no difficulty in persuading the Pope to annul a marriage which dragged like a heavy chain round his god-daughter's neck.

This was the first time Marianne had entered the state apartments of the Tuileries. The salle des Maréchaux, where the concert was to be held, overwhelmed her with its size and magnificence. Once the guardroom of Catherine de Medici, it was a vast chamber rising to two storeys below the dome of the central section of the palace. On the level of the upper storey, facing the dais where the performers were to stand, was a huge box in which the Emperor and his family would soon take their places. This box was supported on four gigantic caryatids completely covered in gold leaf, representing armless female forms in classical draperies. From either side of the box, balconies ran right round the room, entered by means of archways draped, like the doors and windows elsewhere in the hall, in red velvet scattered with gold bees. The roof was a rectangular dome, the corners occupied by massive, gilt trophies, with, in the centre, a colossal chandelier of cut crystal. The dome itself was adorned with allegorical frescoes and, to enhance the warlike aspect of the room, the lower walls were decorated with full-length portraits of fourteen marshals, interspersed with busts of twenty-two generals and admirals.

Although the vast room and the balcony were full of people, Marianne felt lost, as though in some huge cathedral. The noise was like an aviary run mad, drowning the sounds of the musicians tuning up their instruments. So many faces moved before her eyes that for the moment, in the shifting blur of colours and flashing jewels, she was incapable of recognizing any that she knew. At last, she saw Duroc, magnificent in the violet and silver of the Grand Marshal of the Palace, coming towards her, but it was to Clary that he spoke.

'Prince Schwartzenberg is asking for you, monsieur. If you will be good enough to join him in the Emperor's private office.'

'In the Emperor's —'

'Yes, monsieur. I should not keep him waiting, if I were you.'

The young Prince met Marianne's eyes with a look of alarm. This summons could mean only one thing: the Emperor was already aware of the incident of the carriage and poor Clary was in for a dressing down. Unable to let her friend bear the blame for her action, Marianne intervened.

'Monsieur, I know what the Prince is summoned to his majesty for, but as the matter concerns myself alone, let me be allowed to go with him.'

The Duke's frown did not lighten and the look he bent on the young woman before him was stern.

'Mademoiselle, it is not my place to admit to his majesty's presence those who have not been sent for. I am in fact instructed to escort you to Messieurs Gossec and Piccini who await you with the orchestra.'

'Monsieur le Duc, I beg you. His majesty may be committing a grave injustice.'

'His majesty is well aware what he is about. Prince, you are expected. Will you go with me, mademoiselle?'

Marianne was obliged to part from her companion and follow the Grand Marshal. A faint rustle of applause greeted her as she passed but, absorbed in her own thoughts, she paid no attention to it. She placed one hand timidly on Duroc's arm.

'Monsieur, I must see the Emperor.'

'You shall see him, mademoiselle. His majesty has condescended to say that he will see you after the concert.'

'Condescended – you are very stern, monsieur. Are we no longer friends?'

Duroc's face relaxed into a faint smile.

'We are still friends,' he murmured hurriedly, 'but the Emperor is very angry, and my duty forbids me to show it.'

'Am I – am I in disgrace?'

'That I cannot say. But it looks a little like it.'

'Then you may safely resign her to me for a moment, my dear Duroc.' The pleasant, drawling voice came from behind Marianne. 'We disgraced persons should support one another, eh?'

Even before that final 'eh?', Marianne had recognized Talleyrand. Exquisite as always in an olive green coat glittering with medals, knee breeches and white silk stockings, his lame leg supported by a gold-headed stick, he was smiling impishly at Duroc as he offered his arm to Marianne.

Not wholly unwilling, perhaps, to be released from his embarrassing charge, the Grand Marshal bowed with a good grace and resigned Marianne to the Vice-Grand Elector.

'I thank you, Prince, but do not take her far. The Emperor will be here soon.'

'I know,' Talleyrand purred. 'Just time to wash poor Clary's head and teach him not to succumb too readily to the wiles of a pretty woman. Five minutes, I am sure, will suffice.'

As he spoke, he was leading Marianne gently towards one of the tall window embrasures. His manner was that of a man enjoying an agreeable polite flirtation but Marianne soon saw that what he had to say was far more serious.

'Clary will probably be getting a severe scold,' he remarked quietly, 'but I fear that the Emperor's chief anger will fall on you. What possessed you? To fling your arms round a cardinal on the steps of the Tuileries, and a cardinal very much out of favour into the bargain? It was scarcely wise – unless that person was very close to you, eh?'

Marianne said nothing. It was not easy to explain her action without revealing her true identity and as far as Talleyrand was concerned she was only Mademoiselle Mallerousse, from Brittany, a person of no consequence whatever, certainly not on familiar terms with a prince of the Church. While she cudgelled her brains in vain for a likely explanation, the Prince of Benevento spoke again, his tone more detached than ever.

'I was at one time closely acquainted with the Abbé de Chazay. He began life as deputy to my uncle, the ducal archbishop of Rheims, at present chaplain to the king in exile.'

Marianne was conscious of a stab of fear, as if the Prince's words were drawing a net tighter about her. She recalled her wedding day and the tall figure and long face of Monsignor de Talleyrand-Périgord, chaplain to Louis XVIII. It was true, her godfather had been on the best of terms with the prelate. It was he, in fact, who had lent the liturgical ornaments for the ceremony at Selton Hall. Without apparently noticing her agitation, Talleyrand continued in the same light voice, smooth and untroubled as a windless pool.

'In those days, I used to live in the rue de Bellechasse, not far from the rue de Lille, then called the rue de Bourbon, and I was on excellent, neighbourly terms with the Abbé's family.' The Prince sighed. 'Ah, those were delightful times! No one who has not lived in the days before 1789 knows anything of the pleasures of life. I do not think I ever met a more handsome couple, or one more tenderly devoted, than the Marquis d'Asselnat and his wife, whose house is now your own.'

In spite of all her self-control, Marianne felt her mind reeling. Her hand tensed on Talleyrand's arm, gripping tightly as she fought to conquer her emotion. She was gasping for breath and her heart was pounding. She felt as if her knees were about to give way under her, but the Prince's face was as serene and expressionless as ever and his heavy lids still drooped incuriously. A tall and very lovely woman dressed all in white, with flaming red hair and a passionate, wilful face, passed close by them.

'My dear Prince,' she said, with the insolence of the very well-bred, 'I did not know you had such a taste for opera.'

Talleyrand bowed gravely.

'My dear Duchess, all forms of beauty have a claim on my admiration, surely you know that, who know me so well?'

'I do know it, but you had better escort the young person to the dais. The little – the imperial couple, I should say – are about to make their entrance.'

'Thank you, madame. I was about to do so.'

'Who was that?' Marianne asked as the beautiful red-head left them. 'And why does she treat me with such contempt?'

'She treats everyone so, and herself most of all since she has finally accepted a post as lady-in-waiting merely to serve an archduchess. She is Madame de Chevreuse. She is, as you see, a great beauty. She is also extremely spirited and far from happy. She suffers from her own passionate nature. You see, she is obliged to say "the Emperor" and "his majesty" in referring to someone who, in private she calls "the little wretch". You may have noticed that she almost let it slip just now. As for her contempt of you —' Talleyrand's bland gaze was turned suddenly on Marianne. 'Your own actions are the reason for that. A Chevreuse will necessarily look down on a Maria Stella – whereas she would have opened her arms to the daughter of the Marquis d'Asselnat.'

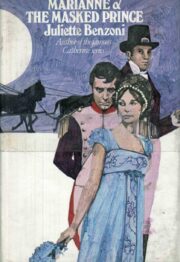

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.