CHAPTER TEN

The Villa dei Cavalli

It seemed to Marianne that she was entering a new world as her coach passed through the huge wrought-iron gates set between high walls, their heraldic bearings a fantastic tracery of black and gold. Its guardians, the two stone giants that stood upon the entry piers, one bearing a lance, the other a drawn bow, seemed to challenge all who would enter these forbidden precincts. The gates swung open as if by magic at the horses' approach. No gatekeeper appeared, nor was there any sign of the dogs which had so alarmed the militia captain. Not a soul was in sight. Within, a long, sanded avenue lined with tall, black cypresses and lemon trees in stone urns, gave on to a wide expanse of green, a peaceful prospect stretching away until the view was closed by the tall, misty plumes of fountains rising from a lake.

As the carriage advanced up the smooth drive, park-like vistas opened up with glimpses of a romantic landscape peopled with statues, massive trees and soaring fountains, a world where water reigned supreme but from which flowers were absent. Marianne stared about her, holding her breath as if time had stood still, a prey to a terror she could not control. Opposite her was Agathe, her pretty face fixed in a faintly apprehensive expression. Only the cardinal, absorbed in his own thoughts, seemed unconscious of his surroundings and immune from the strange melancholy of the place. Even the sun, which had been shining as they left Lucca, had disappeared behind a thick bank of white cloud, pierced now and then by broad shafts of light. The day had grown suddenly oppressive. No birds sang, there was no sound at all but the melancholy song of the water. Within the carriage, no one spoke and even Gracchus on his box forgot to sing or whistle as he had been in the habit of doing all through that endless journey.

The berline rounded a bend, past a grove of gigantic thuyas and emerged into a dream. A long lawn adorned with statues of prancing horses, and where white peacocks trailed their snowy plumes, led up to a palace whose ordered serenity was mirrored in still waters and backed by blue Etruscan hills. White walls, surmounted by balustrades, tall windows gleaming around a great loggia, its columns interspersed with statues, an old dome rising above the central body of the house crowned by a figure mounted on a unicorn: this was the dwelling of the unknown Prince, renaissance with touches of baroque magnificence, on the threshold of a legend.

Arrows of sunlight shot through the great trees massed on either side of the vast lawn, illuminating here and there in the depths of a glade the graceful lines of a colonnade or a leaping waterfall.

Out of the corner of his eye, the cardinal watched the effect of all this upon Marianne. Wide-eyed, with parted lips, she sat as if drinking in the beauty of this enchanted domain through every fiber of her being. The cardinal smiled.

'If you like the Villa dei Cavalli, it is in your power to remain here for as long as you wish – for ever if you will.'

Marianne ignored the subtle hint but asked instead: 'The Villa dei Cavalli? Why that?'

That is the name given to it by the people hereabouts. The villa of the horses. It is they who are the real masters here. The horse is king. For more than two centuries the family of Sant'Anna has possessed a stud which, if any of its products ever left it, would no doubt rival the fame of the Duke of Mantua's celebrated stables. But, except for occasional magnificent gifts, the princes of Sant'Anna have never parted with their animals. Look —'

They were nearing the house. To one side Marianne saw yet another fountain, the water spouting from a huge conch shell. Beyond it, between a pair of noble pillars marking, perhaps, the way that led to the stables, a groom was holding three superb horses whose snowy whiteness, flowing manes and long, plumed tails, might have been models for the statues that filled the park. From her earliest childhood, Marianne had always loved horses. She loved them for their beauty. She understood them better than she had ever understood any human being and even the most fiery-tempered had never been known to frighten her. It was a passion which she inherited from her Aunt Ellis who, before the accident which had left her a cripple, had been a notable horsewoman. The sight of these three magnificent animals seemed to her the most comforting of all welcomes.

'They are superb,' she said with a sigh, 'But how do they adapt themselves to an invisible master?'

'He is not so for them,' the cardinal said abruptly. 'For Corrado Sant'Anna they are life's one real joy. But we have arrived.'

The coach swept round in a stylish curve and came to a halt at the foot of an impressive flight of marble steps on which the palace servants were drawn up to welcome it. Marianne beheld an imposing array of white and gold footmen, their powdered wigs accentuating the olive tints of their impassive faces. At the top, where the perron joined the loggia, three figures in black stood waiting. They were a white-haired woman, the severity of whose garments was relieved by a white collar and the bunch of gold keys hanging at her waist, a bald, shrivelled priest who might have been almost any age, and a tall, well-built man with roman features and thick, black, lightly grizzled hair, dressed with impeccable neatness but without real elegance. There was about this latter personage an indefinable air of the peasant, a kind of toughness which only the earth could give.

'Who are they?' Marianne whispered with some alarm as two of the footmen stepped forward to open the carriage door and let down the steps.

'Dona Lavinia has been housekeeper to the Sant'Annas for many years. She is some kind of poor relation. It was she who brought up Corrado. Father Amundi is his chaplain. As for Matteo Damiani, he is both the Prince's steward and his secretary. Get out now, and remember your birth. Maria Stella is dead – once and for all.'

As though in a dream, Marianne descended from the coach. As though in a dream, she climbed the marble steps between the double row of motionless footmen, supported by her godfather's suddenly iron hand, her eyes on the three people above. Behind her, she could hear Agathe's awe-struck gasp. It was not hot, although the sun had come out again, but Marianne felt suddenly stifled. The strings of her bonnet seemed to be choking her. She hardly heard her godfather perform the introductions or the words of welcome spoken by the housekeeper who curtsied low to her as if to a queen. Her body felt as if it were controlled by some mechanism outside herself. She heard herself replying graciously to the chaplain and to Dona Lavinia but it was the secretary who fascinated her. He too seemed to be moving like an automaton. His pale eyes remained fixed stonily on Marianne's face. He seemed to be scrutinizing her every feature, as if he could read there the answer to some question known only to himself, and Marianne could have sworn that there was fear in that relentless stare. She was not mistaken: Matteo's silence was heavy with suspicion and warning. It was clear he did not look with favour on the intrusion of this stranger and Marianne was certain, from the very first, that he was her enemy.

With Dona Lavinia it was quite otherwise. Her serene face held, in spite of the marks of past sufferings, nothing but gentle kindness and her brown eyes expressed complete admiration. Rising from her curtsey, she kissed Marianne's hand and murmured: 'Blessed be God for bringing us so lovely a princess.'

As for Father Amundi, he might carry himself nobly enough, but he did not appear to be in possession of all his faculties. Marianne was quick to notice his habit of mumbling to himself, a rapid, low-pitched gabble that was perfectly incomprehensible and very irritating to listen to. But the smile he bestowed on her was so beaming, so innocent, and he was so clearly pleased to see her that she found herself wondering if he were not by any chance some old friend whom she had forgotten.

'I will take you to your room, Excellenza,' the housekeeper told her warmly. 'Matteo will take care of His Grace.'

Marianne smiled and her eyes went to her godfather.

'Go, my child,' he told her, 'and rest. I will send for you this evening, before the ceremony, so that the Prince may see you.'

Marianne followed Dona Lavinia in silence, repressing the question that sprang instinctively to her lips. She was consumed with a curiosity greater than anything she had ever known, she felt a devouring urge to 'see' this unknown Prince herself, this master of a fairytale domain who kept such wonderful creatures in it. The Prince was to see her. Then why should she not see the Prince? Was the malady with which he was afflicted, as she now suspected, so terrible that she could not approach him? Her eyes rested suddenly on the housekeeper's straight back as she led the way, her keys chinking softly. What was it Gauthier de Chazay had said? It was she who had brought up Corrado Sant'Anna? Surely none could know him better than she – and she had seemed so glad to see Marianne…

'I will make her talk,' she told herself. 'She must be made to talk!'

The interior of the villa was no less magnificent than the gardens. Leaving the loggia, which was decorated in baroque plaster-work with gilded lanterns of wrought iron, Dona Lavinia led her new mistress through a vast ballroom that shimmered with the dull gleam of gold, then through a series of apartments, one of which was especially sumptuous, with delicate red and gold carvings setting off the dark shine of black lacquer panels. This, however, was the exception. The general colours of the house were white and gold, with floors of a black and white marble mosaic on which their feet slid silently.

The bedchamber assigned to Marianne, which was situated in the left-hand wing of the house, was decorated in a similar style. Even so, she found it startling. Here, too, all was white and gold except for a pair of red lacquer cabinets which added a warmer note to the room. The ceiling, however, was painted with trompe-l'œil figures, who appeared to be leaning over the cornice, as though from a balcony, observing the movement of whoever was in the room below. The walls were covered in a profusion of mirrors. On every side, the two dark forms of Marianne and Dona Lavinia were reflected over and over again into infinity, along with the great Venetian bed hung with rich brocades. The bed was raised up on three steps like a throne and flanked by a pair of torchères in the shape of two Negroes dressed in oriental style, bearing clusters of tall red candles on their heads.

Marianne gazed at this magnificence with a kind of appalled wonder, while the servants carried in her trunks.

'Is – is this my room?'

Dona Lavinia threw open a window and applied a deft touch to the massive spray of orange blossoms dripping from an alabaster vase.

'It has belonged to every Princess Sant'Anna for two hundred years. Do you like it?'

To avoid the necessity of answering, Marianne asked another question.

'Why all these mirrors?'

At once, she had the feeling that the question was an unwelcome one. The housekeeper's worn features tensed a little, and she turned away to open a door leading into a small room apparently hollowed out of a block of white marble. A bathroom.

'Our Prince's grandmother,' she said at last, 'was a woman of such remarkable beauty that – that she desired to contemplate herself continually. It was she who ordered the mirrors put in here. They have been allowed to remain —'

Her tone intrigued Marianne who found her curiosity about this family increasing all the time.

There is no doubt a portrait of her somewhere in the house,' she said with a smile. 'I should like to see her.'

'There was one – but it was destroyed in the fire. Would your ladyship care to rest, a bath, perhaps, or a little refreshment?'

'All three, if you please. But first, a bath. Where have you put my maid? I should like to have her near me.' This was to the obvious relief of Agathe who, ever since entering the villa, had been walking on tiptoe as though in a church or a museum.

'In that case, there is a small room at the end of this passage.' As she spoke, Dona Lavinia pressed a knob on one of the carved panels. The join was so fine that the door was wholly invisible. 'A bed shall be set up there. I will prepare the bath.' She was about to leave the room when Marianne stopped her.

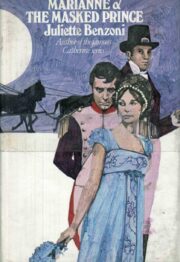

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.