While Arcadius was seeing Madame Hamelin to her carriage, Marianne threw a cushion on to the floor in front of the fire and sank on to it with a weary sigh. She felt chilled and wondered if from pretending to be ill she was really becoming so. But the sickness was all in her heart, racked by doubts, anxieties and jealousy. Outside, a cold, wet night was setting in, so much in tune with Marianne's own mood that for a moment she glanced almost gratefully at the dark windows framed in gold damask curtains. Why must they talk to her of work? She was like a bird, only able to sing when her heart was light. Besides, she had no wish to fall into the conventional pattern of opera singers. Perhaps the truth was that she had no real vocation for the theatre. The offers made to her held no temptation. Or was it the absence of the man she loved that had caused this curious reluctance to accept?

Her gaze wandered from the window to the hearth and came to rest on the portrait that hung above it. Again, she shivered. All at once she seemed to read in the handsome colonel's dark eyes a kind of ironic pity, not unmixed with contempt for the wretched creature sitting at his feet. In the warm glow of the candlelight, the Marquis d'Asselnat seemed to be stepping out of his smoky background to shame his daughter for proving unworthy of him and herself. The silent condemnation of the portrait was so clear that Marianne blushed. Half in spite of herself, she muttered: 'You cannot understand. Your own love was so simple that I dare say to die together seemed to you a logical conclusion, the perfect consummation. But for me —'

Her attempt to justify herself was interrupted by the sound of Arcadius's soft footfall. He stood for a moment watching the slim figure in black velvet, a dark spot in the bright room, even lovelier perhaps in melancholy sadness than in the fullness of joy. The firelight fell on her high cheekbones and awakened a gleam of gold in her green eyes.

'You must never look back,' he told her softly, 'or look to the past for counsel. Your empire lies before you.'

He trod briskly over to the writing-table, picked up the letter he had brought with him and held it out to Marianne.

'You should at least read this one. A courier, mud to the eyebrows, was handing it to your porter when I came in. He said it was urgent. He looked as if he had travelled a long way in bad weather.'

Marianne's heart missed a beat. Could this be news from Compiègne at last? Snatching the letter she glanced hurriedly at the superscription. It told her nothing. The writing was strange to her, and the seal was plain black. Nervously, she slipped her finger underneath the wafer and opened the missive. It was unsigned and contained only one short paragraph.

'If the Signorina Maria Stella will condescend to come on the night of Tuesday the twenty-seventh to the chateau of Braine-sur-Vesle she will be conferring untold happiness upon her ardent admirer. The name of the domain is La Folie and folly perhaps is the presumption of him who will await her there. Prudence and discretion.'

The letter was strange and stranger still the appointed meeting place. Without a word, Marianne handed the letter to Arcadius and watched him raise one eyebrow as he glanced at the contents.

'Odd,' was his comment, 'but not incomprehensible.'

What do you mean?'

'That now that the Archduchess is actually on French soil, the Emperor is obliged to exercise the utmost discretion. And that the village of Braine-sur-Vesle is on the road between Rheims and Soissons – and it is at Soissons that the new Empress is to spend the night of the twenty-seventh.'

'You think the letter comes from him?'

'Who else would ask you to meet him in that way in such a place? I think—' Arcadius paused, reluctant to name the man whose identity must be concealed. 'I think he means to give you the final proof of his love by spending a few moments with you at the very moment of arrival of the woman he is marrying for reasons of state. That should allay your fears.'

Marianne needed no further persuasion. Her eyes were sparkling and her cheeks on fire, her whole being absorbed in her love, and she could think of nothing but that in a little while now she would be in Napoleon's arms again. Arcadius was right. In spite of all his elaborate caution, he was giving her this one, great, wonderful token of his love.

'I will set out tomorrow,' she announced. Tell Gracchus to have my horse ready.'

Will you not take a carriage? The distance is nearly a hundred miles and the weather appalling.'

'I am advised to be discreet,' she smiled. 'A single rider will attract less attention than a smart carriage with a coachman and outriders. I am an excellent horsewoman, you know.'

'So am I,' Jolival retorted. 'I will tell Gracchus to saddle two horses. I am going with you.'

'Is there any need? You don't think—?'

'I think you are a young woman and the roads are none too safe. Braine is only a village and this rendezvous of yours is to take place after dark in a place not known to me. You must not be thinking I suspect – well, you know who – but I shall not leave your side until I see you in good hands. After that, I shall find a bed for myself at the inn.'

His tone admitted no argument and Marianne did not insist. All things considered, she would be glad of Arcadius's company on a journey that would take three days there and back. But she could not help thinking that it was all rather complicated and would have been much easier if the Emperor had taken her to Compiègne and installed her in a house in the town. However, rumour had it that the Princess Pauline Borghese was at Compiègne with her brother and that she had with her her favourite lady-in-waiting, the very same Christine de Mathis who had preceded Marianne in Napoleon's affections.

What am I thinking?' Marianne asked herself suddenly. 'I am seeing rivals everywhere. I must be jealous. I will have to watch myself.'

The sound of the front door slamming shut came to give her thoughts another turn. It was Adelaide returning from the evening service which she attended on most days, less out of piety, in Marianne's secret belief, than to take a good look at her neighbours. Mademoiselle d'Asselnat had a cat-like curiosity which ensured that she always had some titbits of gossip and observation to bring home which proved that her Maker had not held her undivided attention.

Taking the hand Arcadius held out to her, Marianne got to her feet and smiled.

'Here is Adelaide,' she smiled. 'We shall have all the latest gossip while we dine.'

CHAPTER TWO

A Little Country Church

Some time the next afternoon, Marianne and Arcadius dismounted before the inn of the Soleil d'Or at Braine. The weather was horrible: a steady downpour had been drowning the country round about since daybreak, and in spite of their heavy cloaks the two riders were drenched to the skin and in urgent need of shelter and something hot to drink.

They had been travelling since the previous day, making as much speed as possible; Arcadius wanted to see the lie of the land before the time set for the strange meeting. They took two rooms at the inn, the one modest hostelry the village boasted, and then made their way to the coffee room, empty of customers at this hour, to partake respectively of a bowl of soup and a cup of mulled wine. In a little while, an hour or two at most, the new Empress of the French was to pass through Braine on her way to Soissons where she was to dine and stay for the night.

Rain or no rain, the whole village was out of doors, dressed in its holiday best, gathered under the garlands and the fairy lights that were sizzling out one by one. A dais draped in the colours of France and Austria had been set up near the church where the local dignitaries would be taking their places under umbrellas to address the new Empress as she passed through. Through the open door of the fine old church came the sound of the choir practising its hymn of welcome to the cavalcade. Only Marianne felt more miserable than ever, although her gloom was shot through with curiosity. When the time came, she would go out with the rest to catch a glimpse of the woman she could not help thinking of as her rival, that daughter of the enemy who, simply because she was born on the steps of a throne, dared to steal her place beside the man she loved.

Unusually for him, Arcadius was as silent as Marianne. He leaned his elbows on the coarse-grained wooden table, polished by generations of other elbows, staring into the deep purple wine steaming in the pottery bowl before him. He seemed so abstracted that Marianne was impelled to ask what he was thinking.

'About your assignation for tonight,' he told her and he sighed.

'Now that we are here, it seems stranger than ever. So strange that I am beginning to wonder if the message can have come from the Emperor.'

'Who else? And why not from him?'

'What do you know of the chateau of La Folie?'

'Why, nothing. I have never been here before.'

'I have, but so long ago that I had almost forgotten. The landlord refreshed my memory just now when I called for our order. The chateau of La Folie, my dear, is the charming pile you may perceive from where we sit. It seems to me a rather sombre setting for an amorous tryst.'

As he spoke, he pointed to a wooded eminence rising steeply from the far bank of the River Vesle where the massive, half-ruined shape of a thirteenth-century castle loomed in medieval decay through the grey curtain of rain. Walls blackened by time and warfare presented a sinister appearance which the budding green of the surrounding trees was powerless to dispel. Marianne frowned, conscious of a strange wave of foreboding.

'That Gothic ruin? Is that the castle I am to visit?'

'That and no other. What do you think of it?'

For answer, Marianne stood up and swept up the gloves she had placed on the table by her place.

'That it may well be a trap. I have seen them before. Remember the circumstances of our first meeting, my dear Jolival, and our tender treatment at the hands of Fanchon Fleur-de-Lis in the quarries of Chaillot. Will you go and fetch the horses? We'll pay a visit to this unlikely love nest here and now, although I would give much to be mistaken.'

She had been in a strange mood ever since leaving Paris. All along the road that was bringing her nearer her lover, Marianne had been unable to repress a sense of reluctance and uneasiness which may have been because the all-important letter had not been written in his own hand, and because the place appointed was on the very road the Archduchess must take. This last objection had been partly done away with at Soissons where she learned that the place where the Emperor was to meet his betrothed for the first time, on the afternoon of the twenty-eighth, was at Pontarcher, some seven or eight miles from Soissons on the road to Compiègne, yet not, after all, so very far from Braine. Napoleon would have plenty of time to rejoin his suite early in the morning.

Now, the prospect of activity was doing her good, dragging her out of the slough of uncertainty and vague disquiet in which she had wallowed for the past week. While Arcadius went for the horses, she drew from her belt the small pistol which she had taken the precaution of bringing with her from Paris. It was one of those which Napoleon himself had given her, knowing her familiarity with fire-arms. Coolly, she checked the priming. If Fanchon Fleur-de-Lis, the Chevalier de Bruslart or any of their unpleasant followers were waiting for her behind the ancient walls of La Folie, they would be in for something of a surprise.

She was about to leave the table which stood near the room's only window when something drew her attention to the other side of the street. A large, black travelling coach, bearing no arms on the panel but drawn by a team of very fine greys, was drawn up outside the blacksmith's shop. The coachman, muffled in a vast, green overcoat, was standing with the smith by one of the lead horses and both men had their heads bent over what was no doubt a faulty shoe. There was nothing unusual in this sight but it held Marianne's attention. It seemed to her that the coachman was familiar.

She leaned forward to catch a glimpse of the occupants of the coach but could see nothing beyond two vague, but undoubtedly masculine, figures. Then, suddenly, she bit back a cry. One of the men had leaned forward for a second, probably to see how the coachman was getting on, revealing through the window a pale, clear-cut profile surmounted by a black cocked hat, a profile too deeply engraved in Marianne's heart for her to fail to recognize him. It was the Emperor.

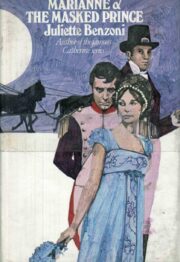

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.