'Drive on to Compiègne, and don't spare the horses!'

'But sire,' the Queen of Naples murmured protestingly, 'we are expected at Soissons. There is to be a supper, a reception.'

'Then they can eat their supper without us. It is my wish that my lady wife spend tonight in her own house! Drive on.'

Caroline's lips tightened at the snub but she retired into her corner and the carriage moved off, affording Marianne a last glimpse through her tears of Napoleon smiling blissfully at his bride. A shout of command and the escort quickened their pace to a trot. One by one, the eighty-three vehicles of the new Empress's train moved past the church. Marianne stood leaning on the wet stones of the Gothic porch and watched them unseeingly, so deep in her own miserable thoughts that Arcadius had at last to shake her gently to rouse her.

'What now?' he asked. We ought to go straight back to the inn. You are soaked to the skin, and so am I.'

Marianne looked at him strangely.

'We are going to Compiègne…'

'What for?' Jolival sounded suspicious. 'You're up to some foolishness, I don't doubt. What can you do in all this?'

Marianne stamped her foot. 'I wish to go to Compiègne, I tell you. Don't ask me why because I don't know. All I know is that I have to go there.'

She was so pale that Arcadius frowned. All the life seemed to have drained from her, leaving only a mechanical creature. In an effort to rouse her from her frozen stupor, he objected wildly: 'But what about the rendezvous tonight?'

'That no longer concerns me. He did not make it. Surely you heard? He is going to Compiègne. He does not mean to return to this place. How far are we from Compiègne?'

'About forty miles.'

'You see! To horse, and fast. I want to be there before them.'

As she spoke, she was running towards the trees where they had tethered the horses. Hard on her heels, Arcadius persisted in trying to make her see reason.

'Don't be a fool, Marianne. Come back to Braine and let me go and see who is waiting for you tonight.'

'That does not concern me, I tell you. When will you understand that there is only one person in the world I care about? Besides, it is bound to be a trap. I am certain of that now… But I do not ask you to come with me,' she added cruelly. 'I can very well go alone.'

'Don't talk nonsense.' Arcadius shrugged and cupped his hands to throw her into the saddle. He did not blame her for her ill-temper because he knew what she was suffering at that moment, but it grieved him to see her punishing herself in a situation which she was powerless to alter.

He merely said: 'Very well, let's go if you insist.' Then he sought his own mount.

Without answering, Marianne dug her heels into her horse's sides and the creature shot off, making for the little track along the river. The few people who had emerged to witness the scene went back indoors and Courcelles sank back into its accustomed quiet. The damaged coach, provided with a fresh wheel by the local wheelwright, had also disappeared.

Although it had the advantage of them by several minutes, Marianne and Arcadius emerged on to the main highway at Soissons in time to see the imperial coach pass by at the head of the column, having thundered through the town before the shocked and astonished eyes of the Sous-Préfet, the town council and the military who had waited for hours in the pouring rain merely to have the pleasure of seeing their Emperor dash away under their noses.

'Why is he in such a hurry ?' Marianne muttered through clenched teeth. Why does he have to be in Compiègne tonight?'

She was swinging into the saddle again after a change of horses at the Hôtel des Postes when she saw the imperial carriage come to a sudden stop. The door opened and the Queen of Naples, recognizable to Marianne by the pink and mauve ostrich feathers adorning her pearl-grey bonnet, stepped out into the road and marched with an air of offended dignity towards the second coach, the chamberlain trotting at her heels. The steps were let down and, like a queen going into exile, she disappeared within and the procession continued on its way.

Marianne looked inquiringly at Arcadius. What was that about?'

Arcadius was bending over his horse's neck, apparently having some trouble with the bit, and did not answer. Irritated by his silence, Marianne burst out: 'Have the courage to tell me the truth at least, Arcadius! Do you think he wants to be alone with that woman?'

'It is possible,' Jolival conceded cautiously. 'Unless the Queen of Naples has been indulging in one of her unfortunate fits of ill-humour —'

'In the Emperor's presence? Unlikely, I think. Ride fast, my friend. I want to be there when they alight from that coach.'

The mad career began again, splashing through icy puddles, brushing aside the low branches that obscured the unfrequented ways.

It was dark by the time they entered Compiègne and Marianne's teeth were chattering with cold and exhaustion. She kept herself in the saddle only by a prodigious effort of will. Her whole body ached as if she had been thrashed. Even so, they were only moments ahead of the cortege; the rumble of the eighty-three vehicles had never been out of earshot on that endless ride except at moments when they had plunged deep into woods far off the road.

Now, riding through the brightly-lit streets, decorated from top to bottom, Marianne blinked like a night-bird caught suddenly in the light. The rain had stopped. The news had run through Compiègne that the Emperor was bringing home his bride that very night instead of on the morrow as expected, and in spite of the darkness and the weather all the inhabitants were out in the streets or in the inns. Already a large crowd had gathered outside the railings of the big white palace.

The building glittered in the darkness like a colony of fireflies. A regiment of grenadiers stood to attention in the courtyard, ready to march out and line the streets. Marianne dashed the water that dripped from her hat brim out of her eyes.

'When the soldiers come out, we'll take our chance to make a dash for it,' she said. 'I want to get close to the railings.'

'Marianne, this is madness. We will be trampled and crushed to death! There is no reason why anyone should let us through.'

'No one will even notice. Go and tether the horses and then hurry back.'

As Arcadius hurried back towards the lighted doorway of a large inn, all the bells in the town were already ringing.

The cortege had reached Compiègne. At the same time a great shout went up in the darkness. The palace gates opened to make way for the solid mass of grenadiers who carved an orderly furrow through the very thickest of the crowd and formed up in a double line to allow a passage for the coaches. Marianne seized her chance and ran, with Jolival on her heels. The backward movement of the crowd was just enough to let her slip behind the guardsmen's backs right up to the palace railings. One or two voices were raised in protest at the impudence of people who pushed themselves forward where they had no right to, but Marianne was oblivious of everything outside her own purpose. Besides, the first of the hussars were already cantering into the square, reining in their sweating horses. A great roar went up from the crowd:

'Long live the Emperor!'

Marianne had climbed on to the low wall at the base of the gilded railings and was clutching at the wet ironwork with both hands. Now there was nothing but a vast, empty space between her and the great staircase lined with footmen in purple livery bearing torches that flickered brightly in the cold air. The palace windows were filled with a brilliant crowd of people, more people were swarming on to the balconies above and an orchestra appeared on the central balcony overlooking the courtyard. Torches were everywhere. The noise was deafening, its volume swelling as the drums began to roll.

Pages, outriders, officers and marshals clattered up the lane between the grenadiers; then came a coach, followed by another, and another, and another. Marianne's heart was beating wildly under her sodden riding-habit. She stared wide-eyed at the carpeted steps, seeing the broad perron below the triangular pediment fill up with ladies in sweeping gowns and tiaras flashing multicoloured jewels, with men in dashing uniforms of red and gold or blue and silver. She even made out a number of Austrian officers, their white dress uniforms a foil for the orders glittering on their chests. Somewhere a clock struck ten.

Then, as the shouting and cheering rose to fever pitch, there came in sight the travelling coach drawn by eight horses which Marianne remembered all too well. The brass band on the balcony struck up a patriotic tune and the vehicle swept through the open gates and described a graceful curve to draw up before the steps. Footmen hurried forward, torch-bearers streamed down into the courtyard, the drums rolled and all the satins and brocades lining the entrance swept the ground in stately reverence. Through a mist of tears she was no longer able to restrain, Marianne saw Napoleon spring out and turn triumphantly to help out the other occupant of the coach with the tender care of a devoted lover. A spasm of rage dried Marianne's tears at the sight of the Archduchess, very red in the face with her absurd, parrot-feathered bonnet askew and a curious suggestion of confusion in her manner.

Standing, Marie-Louise was taller than her bridegroom by half a head. They made an ill-assorted couple, she all soft, Germanic heaviness, he with his pale skin and Roman nose and all the superficial nervous energy he owed to his Mediterranean blood. Perhaps the only thing that did not jar was the great difference in age, for Marie-Louise was too big to convey any impression of delicate youth. Moreover, neither seemed aware of any incongruity. They were gazing at one another with an apparent rapture that made Marianne suddenly long to commit murder. Only a few days ago this man had been making passionate love to her, swearing with all sincerity that she alone possessed his heart: how could he stand there looking at that great blonde cow like a child at his first Christmas present? She ground her teeth and dug her finger-nails into the palms of her hands to stop herself from screaming aloud.

On the other side of the railings, the newcomer was exchanging kisses with the ladies of the imperial family: the exquisite Pauline, barely able to preserve her countenance in the face of that appalling hat; sober Elisa with her stern, classical features; the darkly beautiful Queen of Spain and fair, graceful Queen Hortense, dressed with faultless elegance in a white silk gown and softly-glowing pearls that stood in glaring contrast to the tasteless clothes of the new Empress.

For an instant, Marianne forgot her own grief in wondering what Josephine's gentle daughter, Hortense, must be thinking, seeing this woman dare to seat herself on her mother's still-warm throne. Surely it was unnecessarily cruel of Napoleon to have forced her to be present to welcome this stranger into a French palace? Unnecessary, yes, but characteristic of the Emperor. Not for the first time, Marianne realized that his native kindness was sometimes marred by a streak of inhuman coldness.

'Now will you let me take you indoors out of the cold?' Arcadius's friendly voice spoke in her ear. 'Or do you mean to spend the night clinging to these railings? There is nothing more to see.'

Marianne came to herself with a shiver and saw that he was right. Except for the carriages, the grooms and servants already leading the horses away to the stables, the court was empty. The windows were closed and the crowd in the square was drifting slowly, almost regretfully away, like an ebbing tide. The face she turned to Arcadius was still wet with tears.

'You think I am mad, don't you?' she said softly.

He smiled affectionately and slipped a brotherly arm about her shoulders.

'I think you are very young, wonderfully and terribly young. You rush to wound yourself with the blind determination of a frightened bird. When you are older you will learn to avoid the iron spikes that life strews in the path of human beings to tear and wound them, you will learn to keep your eyes and ears shut so as to preserve your illusions and your peace of mind at all events. But, not yet…'

The hostelry known as the Grand-Cerf was full to bursting point when Marianne and Jolival entered it. At first the landlord, running hither and thither like a frantic chicken, was too busy even to attend to them. In the end Arcadius had to lose patience and arrest the worthy man in mid-career by putting out a hand and getting a firm grip on the knotted handkerchief he wore about his neck.

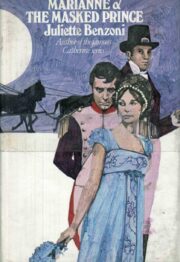

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.