The two women were sitting in the music room talking earnestly when Marianne entered. Clearly, they had not expected her and both turned to stare at her in amazement. Madame Hamelin was the first to recover herself.

'Now, where have you sprung from?' she cried, hurrying to embrace her friend. 'Do you know everyone has been looking for you for a whole day?'

'Looking for me?' Marianne said, removing her cloak and hanging it on the big, gilt harp. 'Who has been looking for me, and why? Adelaide, you knew that I was obliged to go out of town.'

'Yes, indeed!' the old maid said indignantly. 'You were remarkably discreet about it, too, hinting that you were called away on the Emperor's business. So you may imagine my surprise when a messenger came here yesterday from the Emperor himself, inquiring after you.'

Feeling as if the ground had opened under her feet, Marianne sank down on the piano stool and stared at her cousin.

'A messenger from the Emperor? Inquiring after me? But why?'

'Why, to sing, of course! You are a singer are you not, Marianne d'Asselnat?' retorted Adelaide, with such a sting in her voice that Fortunée could not help smiling. It was clear that the thing which galled the aristocratic old lady most about Marianne's new life was the fact that she earned her living as a singer. To cut short these recriminations, the Creole stepped quickly over to Marianne and sat down, putting an arm about her friend's shoulders.

'I don't know what you have been up to,' she said, 'and I do not wish to pry into any secrets, but one thing is quite certain: yesterday an official request came from the Grand Marshal of the Palace for you to sing before the Court at Compiègne today.'

Marianne sprang to her feet with a sudden spurt of anger.

'Before the Court, was it? Or before the Empress? Because she is the Empress, you know, ever since last night, even before the wedding ceremonies have been completed!'

Fortunée blinked at this outburst. 'What are you saying?'

'That Napoleon took the Austrian to his bed last night! He slept with her! He couldn't wait for the wedding ceremony and the cardinal's blessing! He was so besotted about her, it seems, that he could not help himself! And now he dares – he dares to order me to go and sing before that woman! I, who only yesterday was his mistress!'

'And are still,' Fortunée observed placidly. 'My dear child, you must understand that to Napoleon there is nothing in the least shocking, or even unusual, in the idea of bringing his wife and his mistress face to face. Let me remind you that he has chosen more than one of his bedfellows from among Josephine's own ladies, and our Empress was obliged on numerous occasions to applaud the performance of Mademoiselle Georges – to whom, moreover, he even made a present of his wife's diamonds. Before your time no concert was complete without Grassini. Our Corsican Emperor has something of the Turk in him. Besides, I dare say he had a secret urge to see how you reacted to his Viennese. Well, he will have to be satisfied with la Grassini!'

'La Grassini?'

'Oh, yes, Duroc's messenger had orders, if the great Maria Stella were unavailable, to settle for the usual stand-by. You were absent, and so it is the opulent Giuseppina who was obliged to sing at Compiègne today. Mind you, I think it may have been just as well. There was to be a duet with Crescentini, the Emperor's favourite castrato, a dreadful, painted creature. You would have loathed him on sight, but Grassini adores him. In fact, she admires him as she does everything Napoleon chooses to honour, and he decorated Crescentini.'

'I wonder why?' Marianne said absently.

Fortunée gave a tinkling laugh which relaxed the atmosphere a little.

'That is the funny part! When Grassini was asked the same question, she said quite seriously: "Ah, but you forget his disability!"'

Adelaide generously echoed Fortunée's laughter but Marianne merely smiled perfunctorily. She was not sorry that she had not been at home. She found it hard to picture herself making her curtsey to the 'other woman' and indulging in a musical flirtation with a man who, apart from his exceptional voice, was no more than a hollow sham and could only make her ridiculous. Besides, she was too much a woman not to hope that, for a few seconds at least, it might occur to Napoleon to wonder where she was that she was unable to attend. Yes, all things considered, it was better so. The next time she beheld the man she loved, it would, she trusted, be in the company of someone who might well give him some anxious moments – supposing him capable of feeling jealousy on her account. The thought made Marianne smile in spite of herself and drew a waspish comment from Fortunée.

The delightful thing about you, Marianne, is that one can say anything to you and be quite sure you are not listening to a word of it. What are you thinking of now?'

'Not what, who. Of him, of course. Sit down, both of you, and I will tell you what I have been doing these last two days. But for heaven's sake, Adelaide, get me something to eat. I am starving.'

While she addressed herself with an energy remarkable in one who had been so ill only the night before to the sumptuous meal which Adelaide conjured up from the kitchen, Marianne described her adventures. But although the account contained a good deal of humour at her own expense, it did not make her two hearers laugh. Fortunée's expression, when she had finished, was extremely serious.

'But this assignation?' she said. 'It might have been important. Should you not have sent Jolival, at least?'

'I thought of it, but I did not want to part from him. I felt – so very desolate and unhappy. Besides, I am convinced it was a trap.'

'All the more reason to be sure. What if it were your – your husband?'

There was silence. Marianne set down the glass she had just drained with a bang that snapped the delicate stem. Her face was so white that Fortunée took pity on her.

'It was only an idea,' she said gently.

'But one that might have been checked. All the same, I don't see what motive he could have for getting me to that ruined castle, although I admit I did not think of him. I was thinking rather of the people who kidnapped me once before. What can I do now?'

'What you should have done straight away: inform Fouché and then wait. Whatever the attempt on you was to have been, whether it was a trap or a genuine rendezvous, there will certainly be another. By the way, let me congratulate you.'

'On what?'

'On your latest Austrian conquest. I am delighted to see you have decided to take my advice. You will find the faithlessness of men much easier to bear when you have another all ready to hand.'

'Not so fast,' Marianne said, laughing. 'I have no intention of doing more than being seen in Prince Clary's company. His great attraction, you see, is that he is Austrian. I like the idea of amusing myself with a countryman of our new sovereign.'

Fortunée and Adelaide laughed gaily.

'Is she really as ugly as they say?' Adelaide asked eagerly, selecting one of the preserved fruits provided for her cousin.

Marianne did not answer at once. She half-closed her eyes, as if it helped her to conjure up the vision of the intruder, and a wicked smile curved the soft lines of her mouth. The smile was all woman.

'Ugly? No, not exactly. It is hard to say, really. She is more – commonplace.'

Fortunée sighed exaggeratedly. 'Poor Napoleon. What has he done to deserve that! A commonplace wife, when he loves only the exceptional!'

'If you ask me, it is the French who have done nothing to deserve it,' Adelaide exclaimed. 'A Habsburg is bound to be a disaster.'

'Well, they do not seem to think so,' Marianne said with a laugh. 'You should have heard the cheering in the streets at Compiègne!'

'At Compiègne, maybe,' Fortunée said meditatively. They have very little excitement there, except for hunting parties. But something tells me Paris will not be so easily impressed. The only people who will welcome her arrival here will be those circles who see her as the Corsican's doom and the avenging angel of Marie-Antoinette. The people are far from delighted; they worshipped Josephine and they have no love for Austria.'

Gazing at the crowd filling the place de la Concorde on the following Monday, the second of April, Marianne reflected that Fortunée might well be right. It was a holiday crowd, dressed in its smartest clothes and rippling with excitement, but it was not a happy crowd. It stretched all along the Champs Elysées and was thickest around the eight pavilions which had been erected at the corners of the square. It washed up against the walls of the Garde-Meuble and the Hôtel de la Marine but there was none of the throbbing gaiety of a great occasion.

Yet the weather was fine. The depressing downpour had ceased quite suddenly at dawn, the clouds had been swept away and a bright spring sunshine bathed the opening buds of the chestnut trees in sparkling light. Straw bonnets and hats trimmed with flowers burgeoned on the heads of the Parisiennes and their male escorts were resplendent in pale pantaloons and coats of innumerable subtle shades. Marianne smiled at the outburst of seasonable elegance. The population of Paris seemed bent on demonstrating to the new arrival that the French knew how to dress.

Seated with Arcadius and Adelaide in her carriage near one of the prancing stone horses, Marianne had an excellent view of the scene. Flags and fairy lights were everywhere. The Tuileries railings had been newly gilded, the fountains were running with wine and free buffets loaded with food had been set up in red – and white-striped tents under the trees of the cours La Reine, so that everyone might have a share in the imperial wedding feast. Orange trees, glowing with fruit, stood in tubs round the square in readiness for the night's illuminations. Later, when the wedding ceremony had been performed in the great salon carré of the Louvre, the Emperor's loyal subjects would be free to consume four thousand eight hundred pies, twelve hundred tongues, a thousand joints of mutton, two hundred and fifty turkeys, three hundred and fifty capons, the same number of chickens, three thousand or so sausages and a host of other things.

Jolival sighed and helped himself delicately to a pinch of snuff. 'By tonight, their majesties will reign over a nation of drunkards, not to mention the overeating there will be.'

Marianne did not answer. She found the holiday atmosphere both entertaining and irritating. All up and down the Champs Elysées was a sea of little booths containing attractions of all kinds, tiny open-air theatres, dancing, peepshows and shies. From Marianne's carriage, as from any of the others which had come to view the spectacle, it was possible to overhear an endless succession of vulgar jokes which were a clear indication of the prevailing mood. What had passed at Compiègne was common knowledge and no one doubted that Napoleon was about to lead to the altar a woman whose bed he had been sharing for a week, although the civil ceremony had taken place only the day before at Saint-Cloud.

It was noon and the cannon had been roaring for a good half-hour. At the far end of the long vista of the Champs Elysées, lined with the pale green haze of the young chestnut leaves, the sun fell on the huge triumphal arch made of wood and canvas which had been set up in place of the yet unfinished monument to the glory of the Grande Armée. The imitation arch looked well in the spring sunshine, with its brand new flags and the great bouquet placed there by the workmen, the trompe l'oeil reliefs on the sides and the inscription to 'Napoleon and Marie-Louise' from The City of Paris'. The thing was amusing enough, Marianne thought, but it was by no means pleasant for her to see the names of Napoleon and Marie-Louise so coupled together.

The red plumes on the tall shakos of the Grenadier Guards waved all along the route, alternating at the intersections with the red and green cockades of the Chasseurs. Orchestras and bands everywhere were playing the same tune, a popular song called 'Home is where your Heart is' which soon got on Marianne's nerves. It seemed an odd choice for the day when Napoleon was marrying the niece of Marie-Antoinette.

Suddenly, Arcadius's hand, gloved in pale kid, was laid on Marianne's.

'Don't move and don't turn round,' he said softly. 'But I want you to try and take a peep into the carriage that has just drawn up beside us. The occupants are a man and a woman. The woman is a stranger to neither of us but I do not know the man. He has an air of breeding and is very handsome, in spite of a scar on his left cheek – a scar that might have been caused by a sword cut—'

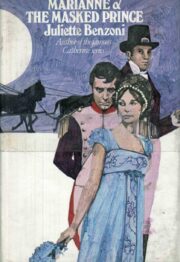

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.