One of the policemen came over to them. The light from his lantern fell on a scrap of yellow paper, the sight of which was enough to rouse Marianne from the depths of horror and grief that had overwhelmed her. Still shaken by sobs, she had heard what was said without being able to gain sufficient control of herself to respond to the inspector's accusations and Jason's angry replies. But this piece of paper, the yellow paper she had seen once before on that day in the Place de la Concorde, in the hands of her worst enemy, acted on her as a counter-irritant because it gave her clear proof; it was the signature added to the nightmare in which she and Jason were caught.

She held out her hand and, taking the paper from the inspector, unfolded it and read it quickly. Yes, it was the same as the one she had already seen, except that it had been brought up to date and the name 'Princess Marianne Sant'Anna' substituted for that of 'Maria-Stella'. But the contents, the accusation that the Emperor's mistress was a spy and a murderess still being sought by the law in England, were the same as ever, still characteristically vile.

Holding it distastefully between finger and thumb, Marianne returned the yellow broadsheet to the inspector:

'You were quite right to keep me here, Monsieur. No one is better able to give you the full story of that abominable piece of libel. I have seen it before. I will tell you, too, how it was I came to know Nicolas Mallerousse, of the kindness I received from him and why I had good cause to love him, whatever ideas you may have formed on the strength of one anonymous letter and another, equally anonymous pamphlet.'

'Madame—' the police officer began impatiently.

Marianne held up her hand. She looked proudly at the inspector with an expression at once so haughty and so candid that his eyes fell before hers:

'Allow me, Monsieur! When I have done, you will see the impossibility of further accusations against Monsieur Beaufort because what I have to tell you will reveal the names of the real perpetrators of this – this hideous crime.'

Her voice failed her as once again her memory set before her every detail of the scene she had just beheld. Her friend Nicolas, so kind and brave, basely slaughtered by the very ones he should have brought to justice. How it came to pass that this should have happened in this house, the house in which Jason was living, a house which belonged to a man of the utmost respectability, Marianne did not know, but she knew with all the infallible insight of her grief and anger, and her hatred also, who had done this. If she had to cry it aloud to the whole of Paris, if it cost her the last shred of her reputation, she would bring the real culprits to justice!

Inspector Pâques, meanwhile, began to lose some of his assurance in the face of a woman who spoke with such firmness and certainty:

'All this is all very well, Princess, but the fact remains that someone committed the crime and the body has been found here…'

'Someone committed the crime but it was not Monsieur Beaufort! The real murderer is the author of that pamphlet,' Marianne cried, pointing to the yellow paper which Pâques still held in his hand. 'He is the man who has hounded me ever since the evil day I married him. He is my first husband, Lord Francis Cranmere, an Englishman—and a spy.'

Marianne could feel, suddenly, that Pâques did not believe. He was looking alternately at the yellow paper and at Marianne with an odd expression on his face. At last he shook the paper softly under her nose:

'In other words, the man you killed? Do you take me for an imbecile, Madame?'

'But he is not dead! He is in France, he goes by the name of the Vicomte—'

'Think of another story, Madame,' the inspector interrupted her roughly, 'and do not try to divert me with these taradiddles! It is easy enough to accuse a ghost. This house is supposed to be haunted, let me remind you. Perhaps that may provide you with a further exercise for your imagination. For myself, I believe in facts.'

In her indignation, Marianne might have continued to plead, reminding this suspicious policeman of her position in society, her influence with the Emperor, her connections, even, despite the shame evoked by the recollection of those dark hours in her life, of her past record as one of Fouché's most trusted agents. But four more policemen came down the path at that moment. Two carried lanterns while the other two were maintaining a firm grip on a burly individual dressed in a seaman's rough woollen jersey which had seen better days.

'Here, Chief!' one of the men said. 'We found this fellow skulking in the bushes, down by the wall on the Versailles road. He was trying to climb over and make off.'

'Who is he?' growled Pâques.

The answer to his question came from an unexpected quarter. It was Jason who spoke. He had taken the lantern from the hands of one of the policemen and held it up so that the light fell on the prisoner. The face emerging from the shadows and from the filthy collar of the seaman's jersey was bony and unprepossessing, with a broken nose and eyes like black coals.

'Perez! What are you doing here?'

The man appeared to be labouring under all the effects of considerable terror. Strong as he looked, he was shaking so that only the grip of the two policemen kept him on his feet.

'You know this man?' Pâques asked, frowning.

'He is one of my men. Or rather, he was, for I discharged him from my ship when we docked at Morlaix. He is an unmitigated rogue,' Jason said sternly. 'I have no idea what can have brought him here.'

The man uttered a howl like a stuck pig, and before the two surprised policemen could stop him he had sunk to his knees on the ground and was crawling to Jason, clutching at his arms, weeping and groaning all at once.

'No, boss!… No, don't do it! Don't give me up!… Mercy!… No my fault… no help it, boss! We go move him, Jones and me, but no time, boss… they here already… police, boss!'

Marianne listened, stupefied, to the frenzied outpouring of disjointed words, spoken in bad French with a strong Spanish accent, without apparent rhyme or reason, yet terrible to her. She knew now that fate was against her and that Inspector Pâques would never listen to her now that he had what seemed to be a real, live witness. Jason, however, losing his temper at last, had the man by the neck of his grimy jersey and was lifting him bodily from the ground:

'Move him? Who? What?'

'B-but-the b-body, b-boss! That dead man!' the wretched creature gasped out, half-throttled. 'Jones say run and he run fast… but I was afraid to run… when I get there… find the gate shut… then I try to climb the wall… Mercy! Don't kill me, boss!'

The last word ended in a strangled choke. Beside himself with anger, Jason had his strong fingers clamped so tightly round the man's windpipe that he all but choked the life out of him. He thrust his keen face hard into the other's congested one. 'Liar!' he spat out. 'What orders have I ever given you except to have you flogged off my ship for a sneaking thief? Say it, you snivelling pickpocket! Admit that everything you've said is lies before I—'

'That's enough!' the inspector cried sharply, springing to the rescue of the unfortunate Perez. 'Let that man go! By trying to kill him you admit the truth of what he says. Here, men!'

The four policemen had not waited to be told. They converged upon Jason, and Perez, abruptly released, dropped heavily to the ground and began fondling his bruised throat and whining. 'Tries to kill me… after all I've done for him… there's ingratitude…'

Seeing that Jason was firmly held, the wretched creature dragged himself slowly to his feet, shaking his head, more in sorrow than in anger, as it seemed:

'Always it is the same, with the fine gentlemen… When things go wrong, they blame the poor wretch who only obeys orders…'

'But this man is lying!' Marianne burst out. She had been watching with a mixture of horror and disgust as this stranger played out his terrible part, for a part it must surely be, just one more act in this fiendish comedy which Francis had devised to ruin Jason, and to ruin her with him. How? By what means was it to be done? She did not know but all her thoroughbred instincts, all the heightened sensitivity of a woman deeply in love cried out to her that this was all part of a plan, lovingly and skilfully prepared.

'Of course he is lying,' Jason said icily. 'But tonight seems to be the night for liars. I don't know what this scoundrel is doing here but he has certainly been bribed.'

'That will have to be gone into,' the inspector said sternly, 'at the trial. In the meanwhile, Monsieur, I arrest you in the name of His Majesty the Emperor and King!'

'No!' Marianne screamed desperately. 'No! You can't do that! He is innocent!… I know he is! I know everything! Everything, I tell you…' She flung herself after Jason who was already being led away by the men. 'Let him go! You have no right!'

Like a fury, she turned on Pâques, who was busy putting handcuffs on Perez and giving him into the care of one of his men. 'You have no right, do you hear? Tomorrow I shall go to the Emperor! He shall know everything! He will listen to me.'

The inspector's hand reached out and caught her arm in a grip of such brutal hardness that she gasped with pain:

'That's enough of that. Be quiet, now, unless you want me to take you along as well! It is not proved that you were an accessory to the crime and I am letting you go free for the present. But you will be watched… and you are free only so long as you keep quiet. One of my men will see you to your coach and escort you home, after which you will not go out again on any pretext whatever. And remember, I shall have my eye on you.'

Marianne's sorely-tried nerves gave way all at once. She sank down on to the stone seat and, laying her head in her hands, began to cry hopelessly, using up what little strength she had left. Two men came out of the billiard-room carrying a stretcher on which lay a large form covered with a cloth which was already showing sinister dark stains here and there. Marianne watched in a kind of daze as it passed by her, her eyes and her mind a blank, beyond knowing even whether her heartbroken tears were for the good, brave man who twice saved her life, whose body they were now taking away, or for the one whom she loved with her whole being and who now stood unjustly accused of a base crime. In her mind, Cranmere's guilt was beyond all doubt. It was he who had engineered all this, he who had woven each of the fine, sticky threads of this deadly spider's web, and he who had murdered Nicolas Mallerousse, killing two birds with one stone, for at the same time he had rid himself of his pursuer and made a bloodbath of the lives of both Marianne and Jason. How could she have been so stupid, so blind as ever for one instant to believe that what he said was true? Her love had made her the tool of a villain and brought about the death of those whom she loved best in the whole world.

She got up slowly, like a sleep-walker, and began to follow the stretcher, a frail ghost in her white dress, its hem still marked with the dreadful traces of the crime. From time to time, a sob burst from her and the sound died away in the quiet, sweet-smelling darkness which had succeeded the storm. After her, a little way behind, not altogether insensitive, perhaps, to the grief of a woman who, only the night before, had had Paris at her feet envying her wealth and beauty, and who now followed this travesty of a funeral procession like a lost and hopeless orphan, Inspector Pâques, too, made his silent way back to the house.

The big white house, a house built for pleasures and happiness, yet where Marianne had seemed to hear the sobbing of a desolate, unhappy shade, emerged through the trees illumined as though for a ball, but Marianne saw nothing but the bloodstained cloth borne before her, heard nothing but the voices of her own grief and despair. At the same mechanical pace she passed the dark groups of policemen on the terraces. She climbed the shallow steps, as though mounting the scaffold, walked through the room where she had known such brief, miraculous happiness and out into the hall, automatically obeying the inspector's voice which came to her from a great distance, telling her that her carriage was waiting at the door.

She was so far away that she did not even flinch when a black figure – another, there had been so many in that last hour! – barred her way. There was no emotion in her eyes as they encountered the burning hatred in Pilar's, she did not even ask herself what Jason's Spanish wife was doing there, and scarcely heard the words which the other woman hissed at her in a passionate fury of denunciation:

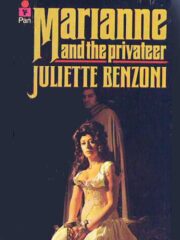

"Marianne and the Privateer" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Privateer". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Privateer" друзьям в соцсетях.