As they went along, Marianne learned that her new friend was called Jacques Cochu, that he owned a patch of land in the nearby village and lived all alone with his grandmother at present, but that he was to be married in a few days' time.

'I'd have waited until spring, myself,' he confided, 'but my grannie wants me to be married before then so I shan't be conscripted. I've been lucky so far because the Emperor hasn't raised any troops this year on account of his marriage. So I'm getting married to Etiennette.'

'Don't you want to go and fight?' Marianne asked, a trifle cast down. Her lively imagination had already decked her saviour out in her own, personal colours. Jacques grinned disarmingly:

'Well, I shouldn't mind it. When I hear the old 'uns talk about Valmy and Italy it fair makes my legs itch. Only, if I go, who will look after the farm? And what would become of my grannie – and Etiennette, too, because her parents are both dead since last year. So I've got to stay.'

'Of course,' Marianne said gently. 'You are quite right. Hurry up and get married and be very, very happy!'

Still talking, they came to a small, spotlessly clean farmhouse in the doorway of which a small, very upright old woman stood waiting for them, her arms folded over her woollen shawl, and looking by no means best pleased at the sight of her grandson coming home in the company of a strange, ragged girl. But when Jacques had given her a rapid account of their meeting and of how he had brought Marianne home with him to be warmed and fed, the ready hospitality of the Valois region was instantly forthcoming. The old woman settled her by the fire with a big bowl of hot soup, cut her a large slice of bread and a thick wedge of bacon, and then began to hunt out some dry clothes while Marianne told her story – or rather the edited version of it which she deemed suitable for the occasion. It went very much against the grain with her to lie to these kind people who had welcomed her with such warmth and generosity but she could not see herself reeling off a list of her pompous Italian titles and so for the present it seemed best to become once again Marianne Mallerousse.

'My uncle was killed very recently in the Emperor's service,' she told her new friends, 'and I was kidnapped by his murderers so that I should not betray them. But I must get back to Paris as fast as I can. I want to avenge my – my uncle, and I have important information to give.'

She wondered for a moment if even this watered-down version of her story might not be coming it rather too strong, but neither Madame Cochu nor Jacques appeared in the least surprised. The old woman, indeed, was already nodding agreement:

'I've never thought much of all those sallow-faced foreign folk we've had roaming about here ever since the Emperor made his brother King of Spain. It was a deal more peaceful before. Not that Joseph's a bad man. Always a kind word and very open-handed! He was well enough liked in these parts and folks were sorry to see him go off to all those savages. As for you, child, we'll do what we can to help you get back home again without a stir.'

'But,' Jacques broke in, 'what's wrong with going straight to the police?'

That was a nasty one and Marianne had to think very quickly indeed in order to make her answer appear sufficiently natural.

'I mean to,' she said earnestly. 'But I must see the minister himself. The people who took me prisoner are members of Queen Julie's court and they have great influence. They have set it about that I was responsible for my uncle's death. There is a search for me, but I must be able to produce proof, and the proof I have is in Paris.'

Having produced this explanation, she permitted herself a faint sigh of relief, hoping that she had been adequately convincing. Jacques and his grandmother had withdrawn to the other end of the kitchen and were holding a whispered colloquy which, though animated while it lasted, was over in a few seconds. Jacques came back to Marianne.

'The best thing,' he said, 'is for you to stay here for a bit and rest. You will be quite safe here. Then, this afternoon I'll take you into Dammartin-en-Goele, to my Uncle Cochu. He's the mayor, and he sends a cart of cabbages and turnips to Paris regularly, every three days. There's one going in the morning. Dressed like a peasant girl, you can go back to Paris without being afraid of the police or of the people who kidnapped you. You'll be there by tomorrow night.'

'Tomorrow night? Marianne made a mental calculation. Jason's trial had begun the day before, it was probably going on at that very moment, while she stayed talking with these good people. Time was precious.

'I suppose,' she objected timidly, 'it isn't possible to be there any sooner? I am in such a dreadful hurry.'

'Sooner? How? Of course, there is the diligence from Soissons – you might catch that in Dammartin tomorrow… but you'd not gain more than a few hours. And you'd not be nearly so safe.'

That was true enough. Naturally, she wished that she could get a horse, but how and where from? She was completely penniless, having left the contents of her purse in Ducatel's hands at the prison. Common sense told her the sensible thing was to accept. The most important thing was to get back and this way she might do so without risk of recapture. It was better to come late than not at all and a trial of such importance was bound to last for several days. In the end, she gave her hosts a grateful smile.

'I agree,' she said, 'and I thank you with all my heart. I hope I may be able to prove my gratitude one day!'

'Don't talk such nonsense,' the grandmother told her gruffly. 'If poor folks don't give one another a hand there's not much good them calling themselves Christians! As for being grateful – well, that's something to keep in your heart. Now you just come and lie down for a bit. There's not much comfort you'll have had sleeping in that nasty wet wood. And while you're having a nap I'll go and see Etiennette, Jacques's promised wife, and borrow a bodice and petticoat from her. The pair of you are much of a size.'

Late that afternoon, dressed in a coarse red woollen skirt and black bodice and bundled up in a black woollen shawl given her by generous Madame Cochu, her feet thrust into a pair of sabots several sizes too large for her and her head enveloped in a huge linen coif, Marianne got up behind Jacques on the crupper of the big cart-horse, used both for riding and on the farm. In front were two big panniers of late apples, fastened to the horse's collar.

It was quite dark when they reached Dammartin, a walled town on a hill, and Jacques handed Marianne into the care of his great-uncle, Pierre Cochu, a fine-looking old man, like an ancient, knotted vine, who took her in with the noble generosity common to tillers of the soil and asked no awkward questions. She was introduced as a cousin of Etiennette's who wanted to go to Paris to work as a laundress in the establishment of a distant relative. Consequently, when the time came for her to say good-bye to Jacques no one thought it anything but perfectly natural that she should throw her arms round his neck and kiss him on both cheeks. But no one there could guess the gratitude which went into that gesture, or why Jacques should have grown so red at being the recipient of this mark of affection. He gave a nervous laugh to hide his embarrassment and said stoutly:

'We'll meet again very soon, Cousin Marie. When we're married, Etiennette and I, we'll come and visit you in Paris. We'll enjoy that…'

'And so will I, Jacques! Tell Etiennette that I shall not forget you, any of you.'

She felt a pang at parting from him. Although she had met him and his grandmother so short a time before, they had been so kind and friendly to her that Marianne felt as if she had always known them. They were suddenly very dear to her and she promised herself that if better times ever came for her she would show them that they had not helped one who was ungrateful. All the same, Jacques was hardly out of sight before Marianne's thoughts had turned once again to their constant obsession with Jason's fate, which was being decided even then, as she was making such efforts to be near him.

After a brief night's rest, spent comfortably enough in a tiny chamber smelling sweetly of wax and citronella, Marianne found herself as day was breaking seated on the driver's seat of a big wagon full of cabbages beside a taciturn fellow who did not utter as much as ten words in the whole course of the journey. They lumbered away peacefully along the road to Paris, far too peacefully, indeed, for Marianne, who nearly died of impatience a hundred times during the interminable drive.

Luckily, it was not raining. The weather was cold but dry. The way was flat and monotonous but Marianne did not succeed in imitating her companion, who dozed a good part of the time, much to the annoyance of his passenger. Whenever she saw his big head nodding, it was all Marianne could do to restrain herself from seizing the reins and setting the whole equipage galloping madly down the endless highway, at the risk of losing all the cabbages. But that would have been a poor return to her friends for all their kindness, so she possessed herself in patience.

All the same, when the spires of Paris appeared at last through the autumnal mists she very nearly shouted for joy and when the wagon reached the village of La Villette and crossed over the site of the unfinished canal of St Denis she had to stop herself jumping down from her seat and running ahead, but she knew it was best to keep up the pretence to the end.

The powerful smell emanating from the city's refuse dump, near which they were obliged to pass, seemed to jerk the driver out of his doze. He opened first one eye, then the second, then turned his head to look at Marianne, but so slowly that Marianne wondered if he were animated by some form of very slow clockwork.

'Tha coozen t'laundress,' he asked 'wheer dost a live? T'mester said t'set thee doon reet by, but ahm f't'market.'

Marianne had had plenty of time on that endless drive to think about what she meant to do when she eventually reached Paris. A return to Crawfurd's house was out of the question and it could prove equally perilous to make for her own. At this point it had occurred to her that by now Fortunée Hamelin might have returned home from Aix-la-Chapelle. The summer season there was over, surely she would be back in her beloved Paris… unless she had sacrificed that love in favour of her other ruling passion for Casimir de Montrond who was officially under open arrest in the Flemish town of Anvers. If that proved to be the case, Marianne decided, she would wait until it was quite dark and then try and slip quietly into her own house in the rue de Lille. So she answered the man: 'She lives quite near the Barrière des Porcherons.' The yokel's dull eye brightened fleetingly: 'T'beant mooch aht't'road. Ah'll set thee doon thar than.' Upon which decisive utterance he appeared to fall asleep again, while ahead of them, by the side of a broad expanse of fresh water, there loomed up Ledoux's elegant rotunda and the guingettes with their red trellises of the Barrière de la Villette.

Safe in her disguise, Marianne did not flinch when the guards made their routine check. Then they were off again, following the wall of the Fermiers Généraux as far as the Barrière de la Chapelle, after which the wagon turned into the Faubourg St Denis. When Marianne's destination was reached they parted without a word spoken and she set out, shaking uncontrollably with the excitement of finding herself in Paris once more, to run to the rue de la Tour d'Auvergne as if her very life depended on it.

It was something of an ordeal because the streets led steeply uphill all the way to the village of Montmartre. To make running easier she had taken off the heavy sabots, which were too big for her and chafed her unaccustomed feet. Consequently, by the time she came to the white house which always in the past offered her such a warm welcome, she was barefoot, red-faced, tousled and panting, but her only fear was that she might find the shutters closed and the house wearing the dismal, unfriendly look common to all houses when the people who live there are away. No, the shutters were open, the chimneys smoking and a vase of flowers could be seen through the hall window.

But when Marianne entered the gate and made to cross the courtyard to the front door, she saw the gatekeeper come running out after her as fast as a pair of very short legs would carry him, holding his arms out wide as if to block her path. With a sinking heart she saw that he was a new man, one she had not seen before.

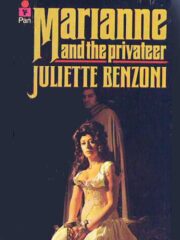

"Marianne and the Privateer" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Privateer". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Privateer" друзьям в соцсетях.