When they let her go at last, she lay unmoving on the ravaged bed, choking with sobs and drowned in tears, exhausted by her body's futile attempts at resistance. She had no more strength even to abuse her ravisher and when Matteo rose, still panting from his exertions, and began, grumbling, to put on his dressing-gown, she could only groan.

'She's so unwilling, there's no pleasure in it! But we'll keep it up, all the same, every night until we're sure. Let her be now, Ishtar, and come with me. That cold creature would put Eros off his stroke!'

So Marianne, broken and defeated, was left in her hated room, alone except for the other two women who remained as mute but watchful guards. No one even took the trouble to cover her. She had ceased to have any hope, even in God. She knew now that she would have to endure every step of this abominable martyrdom, until the time came when Damiani had what he wanted from her.

'But he shan't win – he shan't!' she vowed silently, out of the depths of her misery. 'I'll get rid of the child somehow, or if I fail I'll take him with me…'

Vain words, the desperate ravings born of fever and the paroxysms of humiliation she had suffered, yet Marianne repeated them over and over again in the nights that followed, nights in which even horror began to acquire a kind of monotony. Even revulsion became a kind of habit.

She knew that this was the witch Lucinda taking her revenge, that it was her power reaching out through Matteo from beyond the tomb. Sometimes, in the dark, it seemed to Marianne that she could see the marble statue from the little temple come to life. She heard its laughter… and would wake then in a bath of sweat.

The days were all alike, all dreary. Marianne spent them locked in her bare room under the watchful eye of one of the women. She was fed, bathed, even clothed after a fashion in a kind of loose tunic, like those worn by the black women, and a pair of slippers. Then, when night fell, the three she-devils bound her, for greater convenience, to the bed and left her so, naked and defenceless, to the tender mercies of Matteo. He, in point of fact, seemed to find increasing difficulty in performing what he appeared to regard as some kind of duty. More often than not, Ishtar was obliged to provide him with a glass of some mysterious liquid to revive his flagging powers. From time to time the prisoner's food was drugged, making her lose all sense of time, but she had ceased to care. In the end, overwhelming disgust had finished by inducing a kind of insensitivity. She had become a thing, an inanimate object incapable of reaction or of suffering. Her very skin seemed to have atrophied and grown dull to all sensation, while her sluggish brain held room for only one single, fixed idea: to kill Damiani and then die herself.

This idea, like a persistent, nagging thirst, was the one thing that remained alive in her. Everything else was stone and dead ashes. She no longer knew even if she loved, or whom she loved. All the people in her life seemed as strange and far-off as the characters on the tapestried walls of her room. She had ceased even to think of escape: how could she, guarded as she was by night and day? The she-devils who watched over her seemed incapable of sleep, fatigue or even inattention. All she wanted now was to kill, and then to do away with herself in turn. Nothing else mattered.

They had brought her some books, but she had not even opened them. Her days were spent seated in one of the high-backed chairs, as still and silent as her black guardians, staring at the hangings or at the marks of soot on the ceiling of her room. Words seemed out of place in that room where the silence was like that of the tomb. Marianne spoke to no one and did not answer when they spoke to her. She suffered herself to be cared for, fed and watered with no more response than a statue. Only her hatred was awake amid the silence and the stillness.

At last, this mute indifference began to have its effect on Damiani. As the days passed, Marianne could see the uneasiness growing in his eyes when he came to her at night. Little by little, the time he spent with her grew less until it was only a few minutes, and then, one night, he did not come at all. He had ceased to desire the marble being whose unblinking stare had perhaps power to disconcert him. He was afraid now, and soon Marianne did not see him at all except for the few moments every day when he came to inquire of Ishtar as to his prisoner's health.

He probably thought that by now he had done all he could to procure the child he wanted and that there was nothing to be gained from persisting in what had become a distasteful chore. Somewhere, beneath all her indifference, Marianne had felt a spark of joy at his fears, seeing them as a small triumph, though not enough to appease her hatred: that would only be satisfied with this man's blood, and she had patience to wait for that.

How long did this strange captivity continue, out of time, out of life itself? Marianne had lost all sense of hours and days. She no longer knew even where she was and scarcely who she was. Ever since her arrival she had seen only four people, and yet the palace was built to accommodate a huge staff, although now it was as secret and as silent as the tomb. Every sign of life, apart from the mere act of breathing, seemed to perish there, until Marianne began to think that perhaps death would come to her, creeping quietly of itself without her help. She would simply cease to be. The thing seemed, now, astonishingly easy.

Then, one evening, something did happen.

First of all, the usual watcher disappeared. There was a sound somewhere in the depths of the house, like a hoarse shout. The black woman heard it and, shuddering, left her accustomed place on the steps of the bed and went out of the room, not forgetting to close the door carefully behind her.

It was the first time for many days that Marianne had been left alone but she hardly noticed it. In a moment the woman would be back with the others, for it was near the time usually allotted for her bath. Without interest, she went and lay down on the bed and closed her eyes. The long imprisonment, with its enforced inactivity, was telling on her system. She often felt sleepy during the day and had got into the habit of following her own inclinations as meekly as the will of those outside herself.

She might have slept like that all night but for some instinct which woke her. She knew at once that something unusual had happened.

She opened her eyes and stared about her. It was pitch dark outside and the candles burned as usual in the great candelabra, but the room was as silent and empty as before. No one had come back and the hour for her bath was long past.

Marianne got up slowly and walked a little way across the room. A sudden draught, flattening the candle flames, made her turn her head towards the door and as she did so something stirred in her brain. The door was open.

The heavy oaken panel studded with iron swung back against the wall leaving a black hole between the tapestries. Hardly able to believe her eyes, Marianne moved forward to touch it, to convince herself that this was not simply another of the dreams which haunted her nights, in which, time and again, she had seen the door stand open on to limitless blue distances.

No, surely this time the door was truly open. Marianne could feel the faint draught it created. Even so, to make sure she was not dreaming, she went back to the candles and held one finger up to the flame. At once she gave a little cry of pain. The flame had burned her. Then, as she sucked her smarting finger, her eyes fell on the chest and she cried out again in surprise. There, neatly laid out on the lid, were the clothes in which she had arrived: the olive-green dress with the black velvet trimming, even her shoes and petticoat. Only the hooded cloak edged with Chantilly lace was missing. It was like a memory of another world.

Marianne put out her hand almost fearfully and touched the fabric, stroked it gently and then clutched at it like a drowning man at a straw. Something inside her seemed to snap and come away. She was suddenly alive again, capable of thought and action. It was as if she had been imprisoned in a block of ice and now the ice was broken and pieces were being chipped off and coming back to warmth and life.

With a surge of childlike joy, she tore off the hateful tunic they had put on her and fell on her own clothes as on something infinitely precious. She put them on, revelling in a sensation like feeling herself in her own skin after being flayed. She was so carried away that for the moment she did not even pause to wonder what it meant. It was simply wonderful, even if the heat made the garments uncomfortably hot to wear. She was herself again, from top to toe, and that was all that really mattered.

As soon as she was dressed, she marched determinedly to the door. Whoever had brought the clothes and opened the door must be a friend. She was being given a chance and she must take it.

Outside, everywhere was in total darkness and Marianne went back to fetch a candle to light her way. She saw that she was at the end of a long corridor with no other opening but another door facing her. It seemed to be shut.

Marianne's hand tightened on the candle and her heart missed a beat. Were they merely torturing her with false hopes? Was all this designed simply to bring her, helpless and more desperate than ever, face to face with yet another locked door?

But when she reached it, she saw that it was merely closed, not locked. It yielded to her hand and she found herself in an open gallery like a kind of long veranda, looking down on to a small courtyard. Overhead was a roof of broad, painted wooden beams supported on slender arched columns.

For all her haste to get away from the house, she paused for a moment in the gallery, drawing deep breaths of the warm night air.

It carried with it a disagreeable smell of mud and decaying refuse, but she had not been out of doors for so long and able to see the sky. It made no difference that the sky in question was heavy with cloud with not a star in sight: it was still the sky and therefore the ultimate symbol of freedom.

Resuming her cautious advance, Marianne came to a second door at the far end of the gallery. It opened to her hand and she found herself in China.

All round the walls of the delightful little salon, slant-eyed princesses danced a mad fandango with a joyous troop of grinning monkeys, in and out among black lacquered screens and gilt whatnots bearing quantities of rose and yellow porcelain, over which a Murano lustre cast a shimmering rainbow brightness. It was, in truth, a very pretty room but so much festive illumination made an uneasy contrast with the stillness that reigned there.

This time, Marianne passed on without a pause. Beyond, all was again in darkness, but she was in a broad gallery from which a staircase led, apparently, down to ground level.

Marianne's feet, shod in thin leather, made no sound on the polished marble mosaic as she glided, ghostlike, past the bronze columns that emerged from the walls on either side like ships looming out of the fog, and past the blind stone warriors. Everywhere, on the long inlaid chests, miniature caravels spread their sails to a non-existent wind, and gilded galleys dipped their long oars in invisible seas. On all sides, too, were banners of curious shape bearing the often-repeated crescent of Islam. Lastly, at either end of the gallery, reflected in tall, tarnished mirrors, a great terrestrial globe stood still and useless, dreaming of the tanned hands which had once set it turning in its bronze rings.

Impressed, in spite of herself, by this kind of mausoleum to the warlike, seafaring Venice of other days, Marianne found her feet dragging unconsciously. She had almost reached the staircase when she came to a sudden halt, her heart thudding, and listened intently. Someone was walking about downstairs, carrying a light which was moving slowly along the wall of the gallery.

She stood, rooted to the spot, scarcely daring to breathe. Who was it moving down there? Matteo? Or one of her three sinister keepers? Marianne cast about her for a refuge in case the bearer of the light should come upstairs and catch her unawares. Selecting the statue of an admiral whose armour was partly covered by a cloak with ample folds of stone drapery, she slipped softly behind it and waited.

The light stood still. Whoever it was must have put it down somewhere, because the footsteps went on, growing fainter.

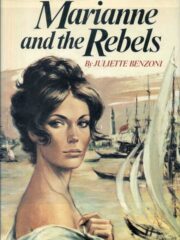

"Marianne and the Rebels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Rebels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Rebels" друзьям в соцсетях.