Senator Alamano's house was situated not far from the village of Potamos, a couple of miles from the town. It was simple, white and spacious, and the surrounding garden was a perfect earthly paradise in miniature – a paradise in which nature, almost unaided, had played the role of gardener. Orange and lemon trees, citrons and pomegranates, bearing flowers and fruit together, alternated with arbours of vines, all tumbling headlong down to the sea. The heady scent of flowers was lightened by the freshness of a spring that tumbled down a bed of mossy rocks to form a tiny stream whose clear waters played mischievous hide-and-seek about the garden with the myrtles and the huge sprawling fig trees contorted with age. House and garden nestled in the hollow of a valley whose slopes were silvered over with hundreds of olive trees.

The woman who ruled over this miniature Eden, and over the senator as well, was small, busy and irrepressibly gay. Much younger than her husband who, although he would never have admitted it, was well on the way to a youthful fifty, Countess Maddalena Alamano had a real Venetian head of hair, made of fire and honey, and a true Venetian way of speaking, fast, soft and slurred, and by no means easy to follow until one got used to it. She was pretty rather than beautiful, with small, delicate features, an impudent tip-tilted nose, eyes bright with mischief, and the prettiest hands in the world. Besides being kind, generous and hospitable, she also possessed a busy tongue, capable of diffusing an incredible amount of gossip in the shortest possible space of time.

The curtsy with which she greeted Marianne on her jasmine-covered terrace was stately enough to have satisfied a Spanish camarera mayor, but she spoilt it immediately by running forward to embrace her with a spontaneity that was wholly Italian.

'I am so happy to see you,' she explained. 'I was so afraid that you would sail right past our island! But now you are here and everything is all right. It is such a pleasure… such a real happiness! And how pretty you are! But so pale… so very pale! Are you—'

But here her husband broke in. 'Maddalena, you are tiring the Princess. She needs rest rather than chatter. She was unwell leaving the boat. The heat, I daresay.'

The Countess snorted.

'At this hour of day? It's practically dark! More likely that abominable smell of rancid oil that's always hanging over the harbour! When are you going to admit it, Ettore, that the oil warehouse ought to be moved. It makes everything smell horrible. Come, dear Princess. Your room is quite ready for you.'

'I am putting you to all this trouble,' Marianne said with a sigh. She smiled in a friendly way at the vivacious little woman. 'It makes me quite ashamed to arrive here and go straight to bed. But it's true, I do feel rather tired tonight. Tomorrow I'll be better, I'm sure, and we shall be able to improve our acquaintance.'

The room which had been made ready for Marianne was pretty and picturesque and very welcoming. The bright red hangings, embroidered in black, white and green by the women of the island, stood out cheerfully against the plain white painted walls which showed up the fine Venetian furniture, in striking contrast to the rustic simplicity of the setting. A touch of comfort was added by the warm red Turkish rugs scattered on the white marble floor, the Rhodes pottery on the dressing-table, and the alabaster lamps. The windows, framed with jasmine, were wide open on the darkened garden but were fitted with fine-mesh screens as a barrier between the mosquitoes outside and the people inside the house.

There was a bed for Agathe in the dressing-room and Jolival, after a flowery exchange of compliments with his hostess, found himself assigned to a room nearby. He had made no comment when Marianne had come to herself again in the senator's carriage but from that moment, his eyes had not left her, and Marianne knew her old friend too well not to discern the anxiety underlying his lighthearted courtesy to their hosts.

After a dinner eaten with the senator and his wife, he came up to Marianne's room to bid her good night, and she saw by the way he quickly extinguished his cigar that he had guessed the real reason for her faint.

'How do you feel?' he asked quietly.

'Much better. I have not felt faint again.'

'But you will do, I think… Marianne, what are you going to do?'

'I don't know.'

Silence fell. Marianne stared down at her fingers, fiddling nervously with the lace edging on her sheet. The comers of her mouth turned down a little, in the way they had when she was going to cry. All the same she did not cry, but when she looked up suddenly her eyes were dark with pain and there was a little roughness in her voice.

'It's so unfair, Arcadius! Everything was going to be all right. Jason was beginning to understand, I think, that I couldn't shirk my duty. He was going to come back to me, I know he was! I could feel it! I saw it in his eyes. He still loves me!'

'Did you doubt it?' Jolival exploded. 'I didn't! You should have seen him just now, when you fainted. He nearly fell in the sea, jumping straight from the stern rail to the quay. He literally tore you out of the senator's arms and carried you to the carriage to get you away from the crowd, who were sympathetic but horribly curious. Even then he would only agree to let the carriage go after I assured him that it was nothing. That quarrel of yours was only a misunderstanding brought about by his pride and obstinacy. He loves you more than ever.'

'Well, misunderstanding won't be the word for it if he ever finds out about – about my condition! Arcadius, we've got to do something! There are drugs, ways of getting rid of – of it.'

'They can be dangerous. These things often end in tragedy.'

'As if I cared! Can't you understand I'd rather die a hundred times than give birth to this – oh, Arcadius! It's not my fault but it disgusts me! I thought I'd washed it all away, but it is too strong. It's come back and now it's taking possession of me! Help me, my friend… try and find me some potion, anything…'

Her head on her knees, cradled in her folded arms, she had begun to cry soundlessly, and to Jolival that silence was worse than any sobs. Marianne had never seemed to him more wretched and defenceless than she was then, finding herself a prisoner of her own body, the victim of a mischance which could cost her all her life's happiness.

After a moment, he sighed. 'Don't cry. It does no good and will only make you ill. You must be brave if you are to overcome this new ordeal.'

'I'm tired of ordeals,' Marianne cried. 'I've had more than my share.'

'Maybe so, but you've got to go through with this one, all the same. I'll try and see if it's possible to find what you want on this island but it's not going to be easy and we haven't much time. The language they talk in these parts nowadays hasn't much in common with the Greek of Aristophanes that I learned at school, either, but I'll try, I promise you.'

Feeling a little calmer now that she had shared some of her anguish with her old friend, Marianne managed to get a good night's sleep and woke the next morning so completely refreshed that she was seized with doubts. Perhaps, after all, her faintness had been due to some quite different cause? There was certainly a most unpleasant smell of oil about the harbour. But in her heart she knew that she was trying to deceive herself with false hopes. There was the physical proof whose presence, or more precisely absence, corroborated all too surely her own spontaneous diagnosis.

As she got out of her bath, she stood for a moment staring at herself in the mirror with a kind of horrified disbelief. It was much too soon as yet for anything to show. Her body looked the same as ever, just as slim and unmarked, and yet she felt for it the kind of revulsion inspired by a fruit that looks perfect outside yet is eaten away by maggots within. She almost hated it. It was as though, by admitting an alien life to enter and grow there, it had somehow betrayed her and become something apart from herself.

'You're coming out of there,' she threatened under her breath. 'Even if I have to have a fall or climb the masthead to do it. There are a hundred ways of getting rid of rotten fruit, as Damiani knew when he tried to keep his eye on me.'

With this object in mind, she began by asking her hostess if it were possible to have the use of a horse. An hour or two's gallop could have amazing results for one in her condition. But when she asked the question, Maddalena looked at her with eyes wide with astonishment.

'Horse riding? In this heat? We have a little coolness here but the moment you are out of the shade of the trees—'

'I'm not afraid of that, and it is so long since I was on horseback that I'm aching for a mount.'

'You're a perfect amazon,' laughed the Countess. 'Unfortunately there are no riding horses here, apart from those belonging to the officers of the garrison. Only donkeys and a few mules. They are all very well for an airing, but if it's an intoxicating gallop you're after, you'd have a job persuading them to do more than a sedate trot. The ground here is generally too steep. But we can go out in the carriage as often as you wish. The country is very beautiful and I should enjoy showing it to you.'

Disappointed in this direction, Marianne agreed readily to everything her hostess had to offer in the way of distraction. She went with her for a long drive through narrow valleys covered with bracken and myrtle where it was deliciously cool, and along the sea shore on to which the Potamos valley and the Alamano's garden debouched. She saw with delight the tiny island of Pontikonisi in its dreamlike bay and the tiny monastery of Blachernes, looking like a small white ink-pot left lying on the surface of the water, with a huge cypress, like a back quill, beside it. They paid a call on the Governor, General Donzelot, at the Fortezza Vecchia and he took them on a tour of inspection and gave them tea.

Marianne inspected the old Venetian cannon and the bronze statue of Schulenburg who had defended the island against the Turks a century before, flirted mildly with a number of young officers of the 6th Regiment of the Line who were visibly dazzled by her beauty, and was generally charming to everyone presented to her, promised to attend the next performance at the theatre which was the garrison's chief amusement, and finally, before returning to Potamos where the Alamanos were holding a grand dinner party in her honour, knelt for a few moments before the sacred relics of St Spiridion.

St Spiridion had been a Cypriot shepherd who rose, by reason of his virtue and ability, to be Bishop of Alexandria. His mummified body had been acquired from the Turks by a Greek merchant who gave it as a dowry with his eldest daughter on the occasion of her marriage to an eminent Corfiot named Bulgari.

'And ever since then, there has always been a priest in the Bulgari family,' Maddalena concluded in her vivacious way. The one who showed you the relic and took some money from you is the latest.'

'Why? Have they still such reverence for the saint?'

'Well, yes, of course. But it's more than that. St Spiridion represents the greater part of their income. They didn't give him the Church, they only, as it were, hired him out. Rather a come-down for a great saint, don't you agree? Not that he doesn't answer prayers just as well as any of the rest. He's a splendid saint, for he doesn't seem to bear a grudge at all.'

Even so, Marianne dared not ask the one-time shepherd to intercede for her. Divine aid was not for her in the deed she contemplated. That was more a matter for the devil.

The grand dinner at which she was the guest of honour in white satin and diamonds seemed to her quite the longest and most boring she had ever sat through. Jolival had departed that morning first thing for the other end of the island to inspect the excavations which General Donzelot was undertaking there. Jason and his officers had been invited but had declined, pleading the urgency of the repairs to the ship, and Marianne, having waited all day in eager anticipation of the evening which would bring her reluctant lover to her, was hard put to it to conceal her disappointment and maintain a smiling face and an air of interest in what her neighbours were saying to her. The left-hand neighbour, at least, for on her right she had General Donzelot who was a man of few words. Like most men of action, Donzelot hated wasting time in conversation. He was polite and friendly but Marianne could have sworn that he shared her own opinion of this dinner as nothing but a tiresome duty.

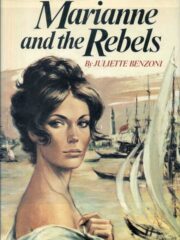

"Marianne and the Rebels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Rebels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Rebels" друзьям в соцсетях.