'Enough!'

The word was roared out in a paroxysm of rage and the man's congested face had turned white with evil marks of venom, but the blow had gone home, as Marianne saw with satisfaction.

He was breathing hard, as though he had been running, and when he spoke again it was in a low, muffled tone, like one suffocating.

'Enough,' he repeated. 'Who told you this? How – how do you know?'

'That is my business! It is enough that I know.'

'No! You will tell me – one day, you will have to tell me. I shall make you talk – because you will obey me now. Me, do you hear?'

'You are out of your mind. Why should I obey you?'

An ugly smile slid, like a slick of oil, across the ravaged features. Marianne braced herself for a foul answer. But Matteo Damiani's anger evaporated as suddenly as it had come. His voice resumed its normal tone and sounded neutral to the point of indifference as he went on:

'I beg your pardon. I lost my temper. But there are things I do not care to speak of.'

'I dare say, but that does not tell me what I am doing here. If I have understood you correctly, then it would seem that I am a – a free woman, and I'd be glad if you would conclude this pointless interview and arrange for me to leave this house.'

'By no means. You don't think I took all that trouble to bring you here, which cost me a great deal of money, besides all the business of bribing agents, even among your own friends, simply for the doubtful pleasure of informing you that your husband was no more?'

'Why not? I can't exactly see you writing me a letter telling me you'd murdered the Prince. For that is what you did, isn't it?'

Damiani did not answer. He plucked a rose from the centre vase and began twisting it nervously between his fingers, as though seeking inspiration. Abruptly, he spoke.

'Let us understand one another, Princess,' he said in the dry voice of a lawyer addressing a client. 'You are here to fulfil a contract. The same contract that you made with Corrado Sant'Anna.'

'What contract? If the Prince is dead, then the only contract which existed, that concerning my marriage, is null and void, surely?'

'No. You were married in exchange for a child, an heir to the name and fortunes of the Sant'Annas.'

'I lost the child, accidentally!' Marianne cried, with a sharp pang of anxiety beyond her control, for the subject was still a painful one.

'I am not disputing the accident and I am sure it was no fault of yours. All Europe knows of the tragedy of the Austrian ambassador's ball, but as regards the Sant'Anna heir, your obligations remain. You must give birth to a child who may, officially, carry on the line.'

'You might have thought of that before you killed the Prince.'

'Why? He was useless in that line; your own marriage is the best proof of that. Unfortunately I am not myself in a position to assume publicly the name which is mine by right. Therefore, I need a Sant'Anna, an heir…'

Marianne seethed with anger, hearing him speak with such cynical detachment of the master he had killed, while at the same time she was becoming aware of an indefinable fear. Perhaps because she was afraid to let herself understand, she fell back on sarcasm.

'There is only one thing you have forgotten. The child was the Emperor's. I don't suppose you'd go so far as to kidnap his majesty and bring him to me, bound hand and foot…'

Damiani shook his head and began to move towards her. Marianne stepped back.

'No. We must do without the imperial blood which meant so much to the Prince. We'll make do with the family blood for this child – a child I'll bring up as I please and whose lands I'll administer gladly for many long years – a child who will be all the more dear to me because he'll be my own!'

'What!'

'Don't look so surprised. You understand well enough. You called me a low thing just now, madame, but no insults can wipe out, or even humble such blood as mine. Like it or not, I am the old Prince's son, and uncle to the poor fool you married. And so, Princess, it is I, your steward, who will give you a child.'

Choked by such effrontery, it was a moment or two before Marianne was able to speak. She had been wrong in her first estimate. This man was nothing but a dangerous lunatic. It was enough to see his fat fingers working, and the way he licked his lips with the tip of his tongue, like a cat. He was a madman, ready to commit any crime to slake his overweening pride and ambition, and to satisfy his baser instincts!

She was suddenly very conscious that she was alone with this man. He was stronger than she and must no doubt have accomplices hidden somewhere about this too-silent house, if only the loathsome Giuseppe. She was in his power. He could force her. Her one chance might be to frighten him.

'If you think for a moment, you will see that you could never carry out this insane plan. I have come back to Italy under the Emperor's especial protection for a purpose which I may not disclose to you. But you may be quite sure that there are people looking for me, concerned about me at this very moment. Soon the Emperor will be told. Do you think you can fool him if I vanish for several months and then turn up with an unaccountable baby? It is plain you do not know him, and if I were you I should think twice before making such an enemy.'

'Far be it from me to underestimate the power of Napoleon. But it will all be very much simpler than you seem to think. In a little while the Emperor will receive a letter from the Prince Sant'Anna thanking him warmly for restoring to him a wife who is now infinitely dear to his heart and announcing their imminent departure together to spend a delightful and long-deferred honeymoon on distant estates of his.'

'And you expect him to swallow that? He knows all about the strange circumstances attending my marriage. Be sure he will have inquiries made, and, however remote our supposed destination, the Emperor will get at the truth. He had his suspicions about what awaited me here—'

'Maybe, but he will be obliged to rest content with what he is told, especially as there will be a note, expressed, naturally, in glowing terms, assuring him of your happiness and begging forgiveness. I have paid, among other things, for the services of a very competent forger. Venice is seething with artists, most of them starving. Believe me, the Emperor will understand. You are lovely enough to explain away any folly, even my own at this moment. The simplest thing, of course, would be simply to kill you and then, in a few months' time, produce a new-born infant, claiming that the mother died in childbed. With a little care, that should go off without a hitch. But I have desired you, ever since the day that old dodderer of a cardinal brought you to the villa, desired you as I have never desired anyone before. That night, you may recall, I concealed myself in your closet while you undressed… your body holds no secrets from my eyes, but my hands are still strangers to its curves. Ever since you went away I have lived in expectation of the moment which would bring you here—at my mercy. I shall get the child I want on your fair flesh… It will be worth a little risk, eh? Even the risk of displeasing your Emperor. Before he finds you, if he ever does find you, I shall have known you tens of times and shall see my child growing in you!… Then shall I be happy indeed!'

Slowly, he had resumed his advance towards her. His bejewelled hands reached out, quivering, towards the girl's slender form. Revolted by the mere thought of their touch, she moved back into the shadows of the room, seeking desperately for some way of escape. But there was none: only the two doors already mentioned.

All the same, she made an effort to reach the one by which she had entered. It was just possible that it might not be locked, that if she moved fast she might be able to get out, even if she had to throw herself into the black waters of the cut. But her enemy had guessed her thought. He was laughing.

'The doors? They open only at my command! Do not count on them. You would break your pretty nails for nothing… Come, lovely Marianne, use your common sense! Isn't it wiser to accept what you can't avoid, especially when you have everything to gain? Who is to say that by yielding to my desires you will not make of me your most devoted slave… and Dona Lucinda once did? I know love – know it in all its ways, and it was she who taught me. If you cannot have happiness, you shall have pleasure—'

'Stay where you are! Don't touch me!'

She was frightened now, really frightened. The man was beside himself, past listening, or even hearing. He was coming for her mindlessly, inexorably, and there was something appalling in the machine-like tread and gleaming eyes.

Marianne retreated behind the table for shelter and her eye fell on a heavy gold salt-cellar standing near the centre-piece. It was a piece like a single carved gem, representing two nymphs embracing a statue of the god Pan: a genuine work of art and probably from the hand of the matchless Benvenuto Cellini. But to Marianne, at that moment, it had only one quality: it must be extremely heavy. She thrust out her hand and grabbed it and hurled it at her attacker.

He side-stepped in time and the salt-cellar flew past his ear and crashed on the black marble floor. The shot had missed but, giving her enemy no time to recover, Marianne had already got both hands round one of the heavy candlesticks, regardless of the pain as the hot wax spilled over her fingers.

'One step nearer and I'll hit you,' she threatened through clenched teeth.

He stood still as she commanded, but it was not from fear. He was not afraid of her; so much was clear from his salacious smile and quivering nostrils. On the contrary, he appeared to be enjoying the moment of violence as if it were a prelude to some voluptuous satisfaction. But he did not speak.

Instead, he raised his arms, the long sleeves slipping down to reveal broad golden armlets fit to have adorned a Carolingian prince, and clapped three times clearly, while Marianne stood speechless, still holding the candlestick ready to bring it down on him.

What followed happened very quickly. The candlestick was wrested from her hands and something black and stifling came down over her head while a hand forced her irresistibly backwards. Then she felt herself lifted by her feet and shoulders and borne away like a parcel.

It was not far, but to Marianne, carried up and down several times, half-suffocated, it seemed interminable. The cloth in which she was enveloped had a peculiar smell, of incense and jasmine combined with another, more exotic odour. She tried to struggle free of it but whoever was carrying her seemed to be unusually strong and her efforts only made them tighten the grip on her ankles painfully.

She felt them climb one more flight of steps and walk forward a little way. A door creaked. Finally, came the feel of soft cushions underneath her and almost at the same moment the light returned. Not before time: the stuff in which she had been muffled must have been remarkably thick, since no air had penetrated it.

She took a few deep breaths before sitting up and looking round to see who had brought her here. The sight that met her eyes was strange enough to make her wonder for a moment if she were dreaming. Three women stood a little way from the bed, eyeing her curiously, but three such women as Marianne had never seen before.

They were all very tall and dressed identically in dark blue draperies with a silver stripe and a multiplicity of bangles, and they were all three black as ebony and so alike that Marianne thought exhaustion must be making her eyes play tricks.

Then one woman moved away from the group and gliding like a ghost towards the open door vanished through it. Her bare feet made no sound on the black marble floor and, but for the silvery tinkle that accompanied her movements, Marianne might have believed her an apparition.

The other two, taking no further notice of her, began lighting a number of tall candles made of yellow wax which were set in large iron candle-holders ranged about the floor. Slowly, the details of the room began to emerge.

It was a very large room, and at the same time sumptuous and sinister. The tapestries hung from the stone walls were picked out in gold, yet the scenes they portrayed were of an almost unbearable violence and carnage. The furniture comprised an enormous oak chest, massively locked, and a selection of ebony chairs covered in red velvet, all suggesting a positively medieval degree of discomfort. A heavy lantern made of gilded bronze and red crystals hung from the beamed ceiling, but was unlighted.

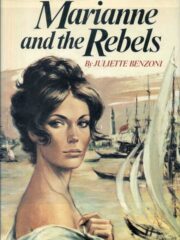

"Marianne and the Rebels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Rebels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Rebels" друзьям в соцсетях.