The two rooms leading out of the large bedchamber showed the same state of dilapidation and neglect, with bare walls showing here and there a glimpse of frescoes in which pallid figures wandered among peeling fields, great overmantels with broken carvings, a complete absence of furniture and abundance of cobwebs so thick they hung like cloudy drapery from the ceiling. For a moment, Marianne wondered if Morvan had brought her to a wholly deserted house but then the sound of voices reached her through a half open door. She went towards them and pushed the door open wider.

The room which met her eyes might just as easily have been the dining room of the great house, by reason of its immense table, the chapter house of a monastery, on account of its vaulted ceiling and the massive, black wooden crucifix on the end wall, or simply a warehouse, from the quantities of chests, bales and packages of all descriptions that lay about on the ancient studded leather armchairs and innumerable stools. A great many of these parcels had been ripped open, revealing lengths of silk or woollen cloth, bales of cotton, bags of tea and coffee, tanned hides and a host of other things, all the more or less recent spoils of wrecks washed up by the sea. But Marianne had scarcely a glance for all this because, right in the midst of all the confusion, a blistering argument was in progress between the chief of the wreckers and a very pretty girl dressed in much the same costume as herself except that her dress was rose pink satin and her shawl of chinese silk embroidered with apple blossoms.

That they were quarrelling was clear only from their angry voices because the words were in the Breton language of which Marianne could not understand a word. She saw, however, that the girl was nearly as dark as herself with a fine pink and white complexion and an expression in her hazel eyes of quite unbelievable hardness. She also noted, with some surprise, that while Morvan had removed his hat, he still wore his black velvet mask. But by this time, the girl had heard someone come in. She swung round and, seeing Marianne, turned her anger against her.

'My dress!' she exclaimed furiously, this time in excellent French. 'You dared to give her my dress – and my shoes, and my beautiful Irish shawl!'

'I did indeed,' Morvan answered her coldly without giving himself the trouble of raising his voice, 'and I shall dare a great deal more Gwen, if you continue to scream in that way. I cannot bear people to scream—'

He was sprawled negligently in a chair, one leg hooked over the arm, playing with what seemed to be a brand new gold-mounted riding whip.

'I shall scream if I like!' the girl retorted. 'That is my dress and I forbid you to give it to her.'

'It was mine before it was yours, since every stitch I gave you. You were half naked when I found you outside the prison in Brest, waiting to see your lover hanged, a thief like yourself – everything you've got on your back you owe to me, my girl. This, and this – and this too!'

With the end of his whip, Morvan lifted the gold chain round the girl's neck and flicked the lace at her sleeves with a contempt that made Gwen shake with fury. When he began to lift her skirts, she slapped them down and screamed at him:

'You gave me nothing, Morvan! What I have, I've earned. It's my share of the loot – and the price of the nights I've given you. As for that one—'

She turned to Marianne as though she meant to take her clothes back then and there but was stopped in her tracks when the other girl said coolly:

'I am sorry, believe me, mademoiselle, if I have unwittingly borrowed your garments, only consider how unfortunate had I been obliged to appear before this gentleman – ' a brief toss of her head indicated the wrecker,' – dressed only in a blanket. I can only add that if you will be good enough to find me some others, I will gladly restore these to you.'

These mild observations acted on Gwen like a shower of cold water. The anger left her face and was replaced by astonishment. She stared at Marianne with new eyes then, after a moment's silence, muttered ungraciously: 'Oh very well! Keep them for now since you've no others. But,' her voice became sharply practical, 'try not to spoil them.'

Marianne smiled. 'I'll do my best,' she said. Gwen's words had told her a good deal and this, with the fact that her lover had been a thief, suggested that she was a peasant girl fallen on hard times. Marianne felt an odd kind of sympathy for her. In the past few days, she too had learned the meaning of fear, suffering and physical wretchedness. In Plymouth harbour she would have done almost anything to save her life and to escape from Jason Beaufort. Besides, this Morvan seemed decidedly unpleasant. There was something in Gwen's voice when she spoke to him that put Marianne instantly on her side out of feminine solidarity. The wrecker may have been aware of this because he sat up suddenly and waved Gwen away.

'Go now. I must talk seriously with this young woman. I will see you later.'

Gwen obeyed, without hurrying. She made her way over to the door, hips swaying under the Chinese shawl, but as she passed Marianne dropped him a wink, heavy with meaning.

'Seriously? She's too well stacked for that! I know you, Morvan. Get a pretty girl within reach, and you can't keep your hands off her. Take care, that's all. If you give her my place as well as lending her my clothes, you'd better watch out for her health – and your own. Have fun!'

Pulling a face at Marianne who felt her earlier sympathy evaporating fast, she swept out with the airs of an outraged queen. But the interlude had at least given Marianne a chance to recover her self-command and now she was able to contemplate the chief of the wreckers without a qualm. He was, after all, only a man and Marianne had determined that no man would ever get the better of her again. Jason Beaufort's kiss, as well as his improper proposal to her, followed by Francis Cranmere's dying words and then by the looks and actions of Jean Le Dru had made her suddenly aware of her own female charm and of the power they gave her. Even the girl who had just gone out, even Gwen had in her vulgar way paid tribute to her beauty. She had said that she was 'well stacked'. Marianne was none too sure of the precise meaning of that curious phrase, but it seemed to be complimentary.

Seeing that Morvan remained slumped in his seat, playing with his curiously braided hair, and did not offer her a chair, she drew one forward for herself and sat down.

'If we are to talk seriously,' she said composedly holding her hands on her silk apron, 'then let us talk. But what are we to talk about?'

'You, myself, our business – I imagine you have a message for me?'

'A message for you? From whom? You forget that I was cast up here by the sea, I was not coming here of my own will. Since I did not anticipate the honour of your acquaintance, I cannot see how anyone should have given me any word for you.'

For answer, Morvan took from his pocket the blue enamel locket and swung it gently from his fingers.

'The person who gave you this cannot have sent you merely for the pleasure of visiting Brittany in winter.'

'Why should you think anyone sent me, or that I was coming to Brittany? One lands where one can in such a storm! That memento, I owe to my parent's sacrifice. You would do me a kindness by returning that and my mother's pearls. They have no business in your pocket.'

'We'll talk of that later,' Morvan broke in with a smile which made his mask look still more sinister. 'For the moment, I want an answer. Why have you undertaken this perilous crossing at the very worst time of year? No young woman of your name and breeding would undertake such a journey unless she were one of the king's amazons at least – or had a mission!'

Marianne had been thinking fast while Morvan was speaking. She was well aware that her best chance of safety lay in the air of mystery which surrounded her. To tell Morvan the story of the events which had destroyed her world and her illusions would be the greatest folly. While he believed her on the same side as himself, Morvan would treat her well. The idea of a mission was a good one to hold on to. Unfortunately Marianne had never met the exiled royalty and had few contacts among the émigré population apart from Monseigneur Talleyrand-Périgord and, to her regret, the duc d'Avaray. Of course, there was her godfather but she had no proof of the abbé de Chazay's travels being in the service of the right king. God's service would be reason enough.

Through the holes in his mask Morvan's cold eyes were studying the girl. She had not noticed that silence had fallen between them while she was thinking. The wrecker repeated his question.

'Well, this mission?'

'Supposing I have one – and it is possible – it is no concern of yours. I see no reason to confide in you. And further more,' here she allowed a note of insolence to creep into her voice, 'even if I had a message for you I could scarcely give it to you since I do not know who you are.'

'I have told you. I am called Morvan,' he said arrogantly.

'That is not a name. And I would remind you that you have not yet been civil enough to show your face. To me, therefore,' Marianne concluded, 'you are simply a stranger.'

A gust of wind flung open one of the windows, sending it banging back against the wall and whirled through the room lifting the papers which lay on the tables. Morvan rose with a sigh of irritation and went to close it. On his way back, he paused to snuff a candle which was smoking, then came and stood squarely in front of Marianne.

'I will show you my face if I think fit. As for my name, it is long now since I had any but Morvan. I am known by that name, over there,' he added with a nod in the direction from which came the murmuring sound of the sea.

'I have nothing to say to you,' Marianne answered him coldly, 'except to ask you to return what is mine, in other words my possessions and my servant, and let me go on my way – when you have given me something to eat, that is, for to tell you the truth I'm starving.'

'And we shall sup very shortly. I did but wait for you. Let us settle our business first, however. I cannot eat with something nagging at me.'

'I can at any time. So let us get this over if you please, and ask whatever questions you wish.'

'Where are you going?'

'To Paris,' Marianne said with all the satisfaction of one telling the simple truth.

'Who are you going to see? The Red Herring? Or the chevalier de Bruslart? Although I doubt the latter's being in Paris.'

'I don't know. They would find me. I don't know who I have to deal with.'

Now it was Morvan's turn to look thoughtful. But Marianne could guess what he was thinking. He must be reasoning that a girl so young and inexperienced could not be the bearer of any perilous message and, in any case, would be unlikely to know its real worth.

Having reached this conclusion, he smiled at her, that wolfish smile which Marianne hated instinctively.

'Very well. I am willing to accept that and shall not force you to betray your secret – which might have unpleasant consequences for us both. But your coming is a blessing of which I should be foolish not to take advantage.'

'Take advantage? But how?'

'It is like this: I have already sent two messengers, one to the King at Hartwell House, the other to London, to the comte d'Antraigus. Neither has returned and for months now I have had no orders or instructions. I was getting desperate when the sea deposited you here like a miracle. You are a god-send! You could scarcely expect me to let you run away again without first giving me a little help?'

The tone was soft, almost carressing but Marianne forced back a shudder. There was something cat-like in this man and she liked him better when a spitting fury than with velvet paws. However, she managed to conceal her thoughts.

'How may I help you?'

'Easily. By remaining here, as my – guest,' an infinitesimal pause before the word, 'and queen of this sad house. Meanwhile, I shall see to it that your servant, the man by whom you set such store and who seems to me to have the air of something more than a mere servant, is sent back to England. He will go, with a proper escort, to the King – or to Madame Royale. Her Highness must have a great regard for you to have given you this precious locket. She will not be indifferent to the fact that you are detained here, unable to assume your mission, until I obtain satisfaction from the princes, or at least an answer to the question I have asked.'

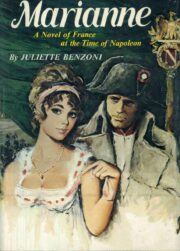

"Marianne" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne" друзьям в соцсетях.