'What must I do?'

Fouché leaned back in his chair, placed his fingertips together and crossed his thin legs.

'I told our friend Surcouf that I meant to entrust you to my wife's keeping merely in order to get rid of him. In fact, I have already found you a situation.'

'A situation? Where?'

'With the Prince of Benevento otherwise vice-grand-elector of the Empire, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord. His wife has need of a reader – and his house is one of the greatest in Paris, perhaps the greatest. For me, at any rate. You cannot conceive how much I like to know of what goes on in such houses.'

Marianne's cheeks flushed with anger and she sprang to her feet, trembling.

'A spy! No, indeed! I will never stoop to that!' Fouché appeared quite unaffected by her excitement. Without even looking at her, he jotted something down on a piece of paper then picked up a spoon from a small silver-gilt tray on which was also a carafe and a glass. He tipped some white powder from a small envelope into the spoon and swallowed it, with a mouthful of water. Then he coughed.

'Ahem! It is up to you, child. I have no wish to force your hand but you should remember, I think, that if St Lazare is no very agreeable dwelling place for a young girl, the English prisons are on the whole rather worse – especially when there is a noose at the end.'

The words fell as inexorably as a sentence.

Marianne sat down again, feeling as though her legs had been cut from under her.

'You would not do that?' she murmured in a choked voice.

'What? Hand you over to the English police? No. But, just supposing Mademoiselle Mallerousse were unwise enough to behave as though she were Mademoiselle d'Asselnat, I should have no choice but to carry out the law. Now, the law gives me two alternatives: to imprison you or to put you back on a boat—'

Marianne pointed silently to the carafe.

'A little water, if you please—'

As she sipped it, she forced herself to think. Fouché had put his cards on the table and she realized that it was useless to hope that he might change his mind. Her best course was to agree, or appear to agree. Afterwards she could try and escape. But where to? She had no idea as yet but it would be time to think of that later, at more leisure. Meanwhile, first things first. At all events, she did not intend to give in without an argument. Putting the glass back on the tray, she said loftily:

'You offer me a situation as a reader? It is not very grand. I am more ambitious.'

'Princess Talleyrand's last reader was a countess fallen on hard times. You cannot expect me to do better than offer you the best house in Paris. But if you prefer to be a scullery maid—'

'I am not amused. Let me remind you that I have no talent for the – the profession you propose, that it is altogether strange to me. I do not even know what I shall have to do.'

'Listen. Keep your ears open and make a note of everything you hear, absolutely everything.'

'I cannot go about with notes in my hand—'

'Don't play the fool with me!' Fouché snapped. 'Your memory is perfect. I saw that from the way you repeated Nicolas's message. Moreover, you speak several languages. That is a valuable asset in the house of a diplomat – even one in disgrace.'

'What do you mean?'

'That the Prince of Benevento is out of favour with the Emperor. He is no longer Minister of Foreign Affairs and his title of vice-grand-elector is no more than a high-sounding sinecure. But that only makes Talleyrand more dangerous. He has vast contacts, formidable intelligence – and—'

'—and you are his enemy!'

'I? No, you mistake me! We have been enemies in the past. But that is ancient history and in politics one forgets quickly. For some time now, we have been the best of friends, do not forget that. But that does not mean I would not like to know the little day to day details in the rue de Varennes. As the princess's reader, you will be present at all large gatherings, you will live in the midst of the household. As I have said, all you will have to do is keep a kind of journal. Every night, before going to bed, you will write a little report on the day.'

'And how will it reach you?'

'Don't worry about that. Each morning, a servant will come into your room to light the fire. He will say: "I hope this wood will burn well". You will give him your report. He will see that it reaches me.'

'How will you know it is mine? Should I sign my name?'

'Certainly not. You will sign it, let me see – yes, with a star like this.'

Fouché drew a quick sketch of a six-pointed star on a piece of paper.

'There! That shall be your emblem – and your name. Here, you will draw the star. That will provide a cover for your real identity. For you will have to take care not to arouse any suspicions in the master of the house. He is perhaps the most intelligent man in Europe. Certainly, the most artful! I would not give much for your chances should he unmask you. So, you have every reason to take care. And, let me say again, that you will not regret working with me. I can reward good service – royally!'

The atmosphere of the office was beginning to weigh on Marianne. She was tired and her head was aching. Exhaustion was taking its own toll. She had slept little on her truckle bed in St Lazare. She rose and going to the window pulled aside the curtain and stood looking out. It was quite dark now but two lanterns burned in the courtyard, revealing the figures of the sentries. Everywhere was strangely quiet. The river Seine glimmered faintly beyond the curtain of trees. From somewhere, came the muffled sound of a harp. The notes came a little discordantly, as though the hands on the strings were clumsy and inexperienced, but this only added to the air of unreality belonging to this evening.

'I must escape!' she thought desperately. 'I must escape – I must get away to Auvergne, to find my cousin. But, for the present, I can do nothing except obey.' Aloud, she sighed, 'I hope you will not be disappointed. I know no one here. How can I know what will interest you?'

Fouché, too, rose and came to stand behind her. She saw his reflection in the glass and smelled the faint odour of snuff which hung about him. When he spoke, his voice was kind and reassuring.

'That is for me to judge. I have need of a fresh eye, of unprejudiced ears. You know nothing and therefore, since you will not know what is important, you will have no temptation to hide anything. Come, now, we will go up and see my wife. What you need is a good supper and a good bed. Tomorrow, I will tell you all you need to know if you are to move safely in your new environment.'

Marianne only nodded, defeated but not resigned. As she followed her persecutor up the narrow private staircase leading from the next room which connected the office with the duchess's apartment, she was thinking already that she would take the first opportunity that offered to run away from this house where she was being sent. After that the choice would be hers. She could either throw herself at the feet of the divorced Empress and beg for her protection, or she could take the first diligence into Auvergne to find her cousin, even if she did turn out to be mad. Better a well-disposed mad woman than an over-intelligent man. Marianne was beginning to feel a hearty dislike for the world of men. It was a selfish, ruthless and cruel world. Woe to her who tried to fight it.

CHAPTER NINE

The Ladies of the Hôtel Matignon

As she followed the imposing servant in white wig and livery of mulberry and grey up the great white marble staircase, Marianne looked dazedly about her and wondered if she had not been brought to some royal palace by mistake. Never, in all her life, had she seen a house like this. It left the ponderous magnificence of Selton Hall far behind, and seemed stern, almost rustic in comparison with the light, graceful elegance of eighteenth century France.

Here, it was all tall mirrors, delicate, gilded scroll work, pale, heavy silks, exquisite Chinese porcelain and thick carpets, softer than smooth lawns underfoot. Outside, the dismal, grey December rain was still deluging Paris persistently. But in here one could forget the dreadful weather. It was as though the house had its own private source of light. And how pleasantly warm it was.

They mounted the stairs slowly, with the dignity befitting a noble household. Marianne's eyes riveted themselves on the solemn workings of the servant's large white calves but her mind was busy going over Fouché's last advice. Now and then, her hand went to her reticule to feel the letter he had given her, a letter written by a woman whom she had never seen but who had written a most moving letter to her dear friend the Princess of Benevento, praising her young friend Marianne Mallerousse's talent as a reader in the most affecting terms. This seemed to be just one example of the magic that could be worked by a Minister of Police.

You will be sure of a welcome, Fouché had told her. The Countess Sainte Croix is an old friend of Madame Talleyrand. They have known one another since the days when she was still Madame Grand with a reputation somewhat less – er, impeccable than it is today. Indeed, your own birth is considerably higher than that of the princess who, however, now bears one of the greatest names in France. This was said no doubt to reassure her. But it did not prevent Marianne from feeling an icy prickle of sweat run down her spine as the great doors, bearing above them the legend Hôtel de Matignon, swung open to reveal the vast forecourt, surrounded by elegant buildings. The army of lackeys in powdered wigs and maid servants in starched caps of whom she caught glimpses, did not improve matters. Marianne felt as though she had been thrust, quite alone and wearing an unconvincing false nose, into the midst of a human sea with snares and ambushes lying in wait on all sides. It seemed to her that everyone must be able to read on her face what she had come to do.

A wave of moist, scented air hit her in the face. Roused from her thoughts, Marianne became aware that the large, purple lackey had given way to a lady's maid in a pink and grey striped dress and lace cap and that she had been introduced into an elegant bathroom with windows giving on to extensive gardens.

A great cloud of fragrant steam was rising from an enormous bath, like a sarcophagus of pink marble, with solid gold taps in the shape of swans' necks. Emerging from the steam, was a woman's head, enveloped in an immense turban and resting on a cushion. Two lady's maids glided like shadows about the exquisite mosaic floor representing the Rape of Europa, bearing armfuls of linen and an assortment of vessels. The walls were lined with mirrors which multiplied to infinity the slender, pink marble columns supporting the ceiling with its painted design of cupids and scenes from mythology. In a corner, beside an enormous vase of flowers standing on the floor itself, a small day-bed upholstered in the same gold shot taffeta as the curtains, awaited the bather. Marianne felt as though she had been suddenly transported inside a large pale pink shell but, in her walking dress, she was instantly far too hot.

She blinked at the extravagance and unaccustomed luxury. Nothing could have been less like the small and primitive toilet arrangements of Madame Fouché.

The woman in the turban, whose face was invisible under a thick mask of greenish jelly, said something Marianne did not catch and pointed languidly to a low stool. Marianne sat down nervously.

'Her highness the princess begs you to wait a moment,' one of the maids said in a whisper. 'She will not be long.'

Marianne turned her eyes away modestly while the waiting women fussed about the bath tub with a great white linen bath sheet and countless small towels. A few moments later, minus her herbal mask and wrapped in a dressing gown of white satin deeply frilled with lace, Madame Talleyrand came to meet Marianne.

'You must be the young person Madame Sainte Croix was speaking about last evening? Have you her letter?'

With a little curtsey, Marianne held out the paper sealed with green wax that Fouché had given her. The princess opened it and began to read while Marianne studied her new mistress curiously. Fouché, in describing the wife of the former bishop of Autun, had revealed her age, which was forty-seven. But there was no denying that she did not look it. Catherine de Talleyrand-Périgord was still a very beautiful woman. Tall and Junoesque, with wide, artless blue eyes under thick dark lashes, a mass of warm gold, naturally curly hair, plump lips, parted to show small perfect teeth, a prettily arched nose and charming smile, she had everything a woman could ask for, in a physical sense at least, for her mind was by no means equal to her looks. Without being as stupid as her numerous rivals claimed, she had a kind of naivety which, joined to great depths of vanity, made her an easy target for ill-natured criticism. If she had not been so lovely, no one would have understood why Talleyrand, the most subtle and accomplished man of his time, should have burdened himself with her and there were few women in Paris more derided. Napoleon himself openly detested her and her husband, tired of her childish prattle, barely spoke to her, although this did not prevent him making quite sure that she was treated with proper respect.

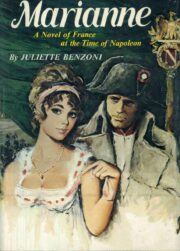

"Marianne" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne" друзьям в соцсетях.