'Well I shall! You see, Arcadius, I should suffer too much if I stayed. He is to remarry again soon, is he not?'

'What then? A marriage of convenience, a dynastic marriage? No such union ever kept a man from his true love.'

'But I am not his true love! I am only a brief interlude in his life. Can't you understand that?'

'Even so. With his help you might become in a few days what you have dreamed of being, a great singer. But you prefer to set off, like Christopher Columbus, to discover America. It may be as well but remember what I say, even at the other end of the world, you will not forget the Emperor.'

'The Emperor…'

For the first time, she realized the splendour of that title. The man she loved bore the loftiest of all crowns. He was the greatest warrior of any age since Caesar and Alexander. Nearly all Europe bowed before him. As though it were child's play, he had won victory after victory, conquered vast territories. As though it were child's play, he had conquered her, had made her bow beneath a love too great for her romantic little soul, a love without even the legendary wings to help her bear the crushing weight of history.

When she spoke her voice was drained of all expression.

'Why do you think that I shall not forget him?'

Jolival sighed gustily, stretched and settled himself back on the straw. He gave a great yawn and then said placidly:

'Because it is not possible. I've tried.'

The hours that followed were, for Marianne, the most agonizing she had ever lived. The absence of a clock made itself cruelly felt because time seemed to her endless when she had no means of measuring it. Jolival did try asking Requin when he brought their one meal of the day but all he got for answer was:

'What difference does it make to you?'

They were forced, therefore, to rely on guess-work. Jolival attempted to soothe his companion's nerves by observing that darkness fell early in winter but nothing and no one could calm Marianne's nerves. So many obstacles lay between her and freedom. Would Beaufort be still there even? Would the boy manage to come back at all or would he be so overcome by the difficulties before him that he would abandon the whole plan altogether? A host of possibilities, each more desperate than the last, occurred to Marianne's fevered mind. There were times when she actually believed she must have dreamed that Gracchus-Hannibal Pioche was there. But for Jolival and his imperturbable calm, she would never have been able to control herself. But the man of letters appeared so calm and relaxed that it was almost irritating. Marianne would have preferred him to share her terrors and her cloudy suppositions instead of simply peacefully awaiting the outcome of events. But then, she reflected, he had little to fear beyond a disagreeable marriage.

Marianne had just returned for the hundredth time to striding up and down their prison when a whisper from Arcadius stopped her in her tracks.

'Someone's coming!' he said. 'Our red-headed saviour can't be far off – if my calculations are correct it must be getting on for nine o'clock.'

Someone was certainly approaching but not from the dead end of the passage. The figure who rose suddenly before Marianne's horrified eyes was that of Morvan. He was enveloped in a great black cloak with drops of water shining wetly on it and his scarred face was without its mask. Marianne could not hold back a cry of terror as he loomed up out of the shadows and her terror was increased at the thought that any moment they might hear Gracchus's pick working away at the loose stones in the wall. The Riders of the Shadows would have no mercy on a lad who to them would be no more than a spy and therefore a potential danger. Marianne's eyes sought Jolival's and read in them the reflection of her own thoughts. He was already standing close beside the bars and suddenly he spoke in a voice much louder than his normal tones.

'It seems we have a visitor! We certainly looked for none, or not of this quality!'

Marianne understood at once that by talking so loudly he hoped to make Gracchus, supposing he were already on the other side of the wall, hear and be on his guard and she too spoke as loudly as she could.

'I take no pleasure in such a visit. What is your business here, sir plunderer of wrecks?'

Morvan's twisted lips curved in an unpleasant smile.

'To see how you are, my beauty! In truth, since we were obliged to part so abruptly, I have thought of you almost constantly – and talked of you too! Your ears must have been burning, we have argued so much about you, the chevalier, the baron and myself—'

'I do not know what you may have said and I do not wish to know, or not from you. The chevalier de Bruslart will no doubt repeat to me the gist of your remarks and from him they are more likely to come correctly.'

Morvan scowled and drew back a pace.

'Do you have to shout like that? I am not deaf! You are almost bursting my eardrums!'

'I am sorry,' Marianne said without lowering her voice. 'But I have been ill and my voice is only audible if I shout.'

'Shout as much as you like, before long you will shout to another tune! This little journey was quite providential. Our dear chevalier has always had an eye for a pretty woman and he was showing signs of quite unnecessary kindness and clemency towards you. He is a simple, tender-hearted soul in whom the old principles of chivalry are still regrettably alive. Fortunately, I had plenty of time to provide him with some detailed information concerning you which, I think, has prevailed upon him.'

Marianne felt her heart quake. It had happened exactly as she had feared. Morvan had turned the chevalier against her. No doubt he had come now to give himself the gruesome pleasure of informing her of her imminent death. But not for anything in the world would she have shown this man the gnawing fear within her. Instead, she turned her back on him with a disdainful shrug.

'My congratulations, if you have succeeded in persuading the chevalier de Bruslart to abandon his sacred principles and murder a defenceless woman in cold blood. You should have made yourself a career in diplomacy! It would have been more honourable than your chosen occupation – although less lucrative perhaps!'

Her words caught Morvan on the raw. He made an angry movement as though he would have thrown himself against the bars but then thought better of it. When he spoke, his voice was light enough but his smile was evil.

'Who mentioned murder? That principle is one of which the chevalier de Bruslart admits no compromise but none the less, you shall be punished as you deserve. I have managed to persuade him to hand you over to our dear Fanchon who seems to take in my view a quite excessive interest in you. She will find you employment for which you are well fitted. And she will also be grateful to the man who can renounce his own vengeance for her profit, and his own.'

'I wonder at the chevalier's scruples,' Marianne retorted, sick at heart, 'that he spares a woman's life and yet dishonours her in a baser fashion!'

'Dishonours? A fine word, coming from you! The chevalier's scruples yielded somewhat after I had told him of your exploits in my barn with that spy of Bonaparte's who was your so-called servant – and also that I found you on the shore clad in the most rudimentary fashion and attempting to seduce two of my men. One of whom, moreover, you murdered not long afterwards. No, after this very circumstantial account, the chevalier had no more hesitation. Especially since he hopes to be your first customer.'

Speechless with horror at this display of cruelty and duplicity, Marianne could find no answer. In her disgust she even forgot Gracchus and his danger but Arcadius Jolival intervened.

'I think that will do, monsieur,' he said his fingers playing nervously with his moustache. 'You have played your foul part to perfection and now I must ask you to leave this lady in peace. As to the worth of Bruslart's scruples, if he accepts the base assertions of a wrecker I can say nothing, but I can tell you what you are at once. You are a first-class scoundrel!'

Morvan's face paled and Marianne saw his jaw tighten. But before he could reply, the chevalier's voice called from the hollow crypt nearby.

'Ho there! Kerivoas! Come here and leave the prisoners alone. We'll settle that afterwards. For the present, we have more urgent business.'

The distant gleam of torchlight was now dancing on the walls and there was a hum of voices not far off. Morvan, who had seemed about to hurl himself bodily at the bars, stopped short and turned on his heel with a shrug.

'I'll come back later to slice off those big ears of yours, little man! Don't worry, you'll lose nothing by waiting.'

He went away to join the others and Marianne went disconsolately back to her straw bed where she sat down with her arms around her knees and her head with its long, tumbled mane of hair resting on her arms.

'This is the end,' she murmured. 'We are finished. And if that poor boy comes now he will be finished with us.'

'Be patient. We shouted loud enough to warn him! He may be on the other side of the wall—'

'What should he wait for? He cannot get near us! The conspirators are still in the crypt and we cannot tell how long they will be there – 'you can hear them—'

'Ssh! Listen!' Jolival said sharply. He went and pressed himself up against the bars as near as possible to the confused voices coming from the crypt.

'They are having a meeting,' he whispered.

'And – can you make out anything?'

He nodded and touched his big ears with a meaning smile. Marianne was silent, watching her companion's mobile features as they grew at first grave and then thoroughly alarmed. She heard a gruff voice which she recognized as belonging to the chevalier de Bruslart but was unable to make out a word of what he said. The leader of the band was speaking. He seemed to be explaining something. From time to time another voice would interrupt but the main burden always returned to Bruslart. And, gradually, the look on Jolival's face became so tragic that Marianne laid her hand on his arm and whispered urgently: 'What is it? You are frightening me! Are they talking about us?'

He shook his head and muttered swiftly under his breath:

'No – in fact, they are going away. Be patient a little longer.'

He listened again but the council seemed to be breaking up. There was a noise of seats being scraped on the floor and a clatter of booted feet. All the voices began speaking at once, then Bruslart's rose above the rest.

'To horse, gentlemen! For God and for the King! Tonight, at last, fortune is with us!'

This time, it was beyond a doubt. They were going. The footsteps died away, the voices faded and the lights vanished. In a few moments, Marianne and Arcadius found themselves once more alone with the heavy silence and the dim, ruddy light of their dungeon. Jolival left his post by the bars and went over to the brazier. Marianne saw that he was avoiding her eyes.

'You heard what they were saying?' she asked.

He nodded affirmatively but did not open his mouth. He seemed to be deep in thought. However, Marianne was too anxious to inspect his silence.

'Where are they going?' she asked with a touch of irritation. 'Why is fortune on their side tonight? What are they going to do?'

Jolival looked at her at last. His mouse-like face, usually so cheerful, was overcast as though by some distressing thought. He seemed to hesitate for a moment then, as Marianne came and clutched his arm anxiously, he said at last:

'I am in two minds whether to tell you but whether or not they are successful you will hear anyway. They have learned from one of their spies in the palace that the Emperor goes tonight to Malmaison. The former Empress is unwell. She has also learned that the Emperor's choice of a wife has fallen definitely on the Austrian arch-duchess and the news has affected her badly. The Emperor's decision to go was taken only an hour ago.'

'And?' Marianne felt her heart beat faster at the mention of the word 'Emperor', only to contract painfully at the news of his impending marriage.

'And they mean to carry out the old plan of Caboudal and Hyde de Neuville, the old plan which ever since the Consulate, Bruslart has always failed to carry off. They will set a trap for Napoleon when he leaves Malmaison, probably very late, stop his carriage, overcome his guard and then carry him off and—'

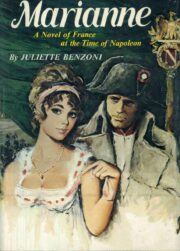

"Marianne" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne" друзьям в соцсетях.