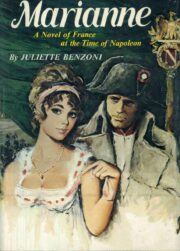

'Come,' the former Empress said again. 'Come and sit here.'

Marianne made a faultless court curtsey. 'Madame,' she murmured, 'I dare not. Your Majesty sees how I am dressed – and the harm I might do to these pretty chairs.'

'No matter,' Josephine cried airily with the sudden playfulness which was so much a part of her charming, unpredictable nature. 'I want to talk to you, I want to find out who you are! The truth is, you are a mystery to me. You are certainly dressed like a vagabond but your curtsey is like a great lady's and your voice goes with it. Who are you?'

'Just a second,' Napoleon broke in. 'Here's another! It seems the conspirators were not the only ones on the road.'

It was indeed Duroc once more, accompanied this time by a thin figure muffled in a furred driving coat in whom Marianne was disconcerted to recognize Fouché. The Minister of Police was paler than ever except for a somewhat red and swollen nose due partly to the cold outside and partly to a magnificent cold in the head which thickened his voice and obliged him to be constantly using his handkerchief. The two men halted side by side and bowed. The Grand Marshal of the Palace spoke first.

'There was indeed a conspiracy, Sire. I found his Grace the Duke of Otranto on the spot, very busy unravelling it.'

'I see.' The Emperor stood with his hands behind his back regarding his two officials in turn. 'How is it, Fouché, that I was not warned?'

'I was not warned myself, sire, until the last moment. But, as your majesty sees, I left my bed at once although my state of health should have kept me there – besides, your majesty's accusation is unjust. You were warned, sire. Is that not Mademoiselle Mallerousse I see there, beside her majesty the Empress? She is one of my most loyal and valued agents.'

Marianne opened her mouth but no words came. Fouché's presence of mind was stupifying. That he should dare to claim the credit for what she had done and take it all to himself, when, but for Gracchus-Hannibal Pioche, she might have stayed in the underground cavern of Chaillot forever!

But Napoleon's blue eye was turned on her and she felt her heart shrink at its hardness.

'One of Fouché's agents, eh? That's news – what have you to say to that, Duroc?'

The words were a threat. The Due de Frioul reddened and groped for a reply but Fouché gave him no time. Smiling, very much at his ease, he dabbed delicately at his nose and purred. 'Indeed yes, one of the best. I even christened her The Star. Mademoiselle Mallerousse is at present reader to the Princess of Benevento. A charming girl! Utterly devoted to your majesty as your majesty no doubt – er, appreciates.'

The Emperor made an angry movement.

'Talleyrand, now?' He turned to Marianne who was terrified by this sudden anger. 'It seems to me, mademoiselle, that there are some explanations you must give me. I had heard of a Demoiselle Mallerousse, a pupil of Gossec's, with a charming voice, but nothing more! I perceive now that your talents are not confined to singing – that you have more than one string to your bow. You are a consummate actress certainly – a great artist, truly! A very great artist! It is true that to be a star with Fouché requires a variety of talents – and a heart to match!'

His voice shook with anger and the harsh Corsican accent became more striking. He was striding furiously up and down the music room as he launched this flood of bitter insults at Marianne's head. Josephine uttered an alarmed protest.

'Bonaparte! Don't forget she may have saved your life!'

The frenzied pacing stopped short and Marianne was crushed beneath a glance so heavy with contempt she felt the tears come into her eyes.

'That is so! I will see to it that you are rewarded, mademoiselle, according to your deserts! His Grace the Duke of Otranto will arrange for a proper sum—'

'No! No – not that!'

This was more than Marianne could bear. It had been cruel enough to be compelled to give up her dream of love and make up her mind to go away from him forever. No one could ask her to endure his contempt as well, to let him treat her like some low servant, a common spy! She was willing to go but not to let him spoil the wonderful memory of their night of love. That, at least, she meant to keep intact to feed her dreams on for the rest of her life. In her indignation, she had sprung to her feet and now stood facing Napoleon, the tears rolling down her scratched and dirty face but with her head held high and her green eyes flashing defiance at the angry Caesar.

'If I tried to save your life, sire, it was not to have you throw money in my face as though I were a servant you had dismissed – it was for love of you! And because I am indeed your servant, though not as you would have it! Is it a crime that I have worked for your police? I do not think I am the only one to do that!' She hurried on regardless of the mortified looks of Josephine who had herself supplied the inquisitive Minister of Police with information about her husband's actions on more than one occasion. 'But I did so,' Marianne went on, too well away for Fouché's warning glance to stop her now, 'I did so only because I was forced to do it. Because I had no choice—'

'Why not?'

The abruptness of the question and the harsh voice in which it was uttered made Marianne's heart miss a beat. He was observing her ruthlessly. This was the end. She had lost him now forever. If that was so, she might as well complete the ruin with her own hands and tell him everything. Afterwards, he could do with her what he liked, throw her into prison, send her back to the gallows in England – what did it matter! She slid wretchedly to her knees.

'Sire,' she said in a low voice, 'let me tell you the whole story and then you can judge fairly—'

Fouché, clearly anxious at the turn events were taking, made an attempt to intervene.

'All this is ridiculous,' he began but a sharp, 'Silence!' from the Emperor cut him short. Marianne went on.

'My name is Marianne d'Asselnat de Villeneuve. My parents died under the guillotine and I was brought up in England by my aunt, Lady Selton. A few months ago, I was married to a man whom I believed then, I loved. It was a terrible mistake. On the very night of my wedding, my husband, Francis Cranmere, staked everything I possessed at cards and lost. He staked my honour also. And so – I killed him!'

'Killed him?' Josephine's horrified exclamation was not altogether unadmiring.

'Yes, madame – killed him in a duel. I know it may seem strange for a woman to fight a duel, but I was brought up like a boy – and had no one left but myself to defend my name and my honour. My aunt had died a week earlier. After that, I was obliged to flee. I had to leave England where I had nothing to look forward to but the hangman's noose. I managed to make my way to France by means of a smuggling vessel – and there, to save me from the laws against returning émigrés, his grace the Duke of Otranto offered me a post as reader to Madame de Talleyrand and at the same time—'

'To render some small services to himself!' The Emperor finished for her. 'It does not surprise me. Never do anything for nothing, do you Fouché? I think you had better tell me how you came to be offering your protection to an émigré returning to the country illegally.'

Fouché's faint sigh of relief had not escaped Marianne. 'It is very simple, sire,' he began. 'It happened this way—'

'Later, later—'

The Emperor had resumed his pacing up and down but much more slowly now. With his hands clasped behind him and his head sunk forward on his chest, he seemed to be thinking. The kindly Josephine took advantage of this to raise Marianne from her knees and make her sit down once more. She wiped the girl's tear-drenched eyes with her own handkerchief and, calling her daughter Hortense who, alone of her entourage, had been present at the scene, asked her to send for a warm drink for Marianne.

'Tell them to prepare a bath and dry clothes, and a room – I am keeping Mam'zelle d'Asselnat with me!'

'Your majesty is very kind,' Marianne said with a sad little smile, 'but I should prefer to go. I should like to rejoin my wounded companion. We were to leave together, tomorrow, for America. His ship waits for him at Nantes.'

'You will do as you are told, mademoiselle,' Napoleon told her shortly. 'Your fate, I think, is not in your own hands. We have not yet done with you. Before you leave for America, you shall have some more explaining to do.'

Explain what, my God? Marianne thought. What a fool she had been to plunge into this wasp's nest in order to save him, or rather, to see him, even for an instant, because she still hoped for something, though for what she could not have said. Perhaps for some return of the other night's tenderness? No, that hard, clipped voice told her all too clearly that she had never meant anything real to him. He was cold and heartless! But then, why did he have to have such a hold on her?

'I am your majesty's to command,' she murmured with death in her heart. 'Command me, sire, and I will obey.'

'I should hope so. Accept the clothes and hot water her majesty is good enough to offer you, but hurry! You must be ready to go with me to Paris within the hour.'

'Sire,' Fouché offered graciously, 'I can easily take charge of Mademoiselle. I am returning to Paris and I can set her down in the rue de Varenne.'

His willingness to oblige earned the Duke of Otranto a swift, angry glare.

'When I need your advice, Fouché, I shall ask for it. Off you go, mademoiselle, and be quick.'

'May I at least know what has become of my companion?' She asked with a measure of determination.

'In the Emperor's presence, Mademoiselle,' Napoleon retorted, 'you need concern yourself with no one but yourself. Matters are already sufficiently black for you. Do not make them worse.'

But it would take much more than Napoleon's anger to make Marianne desert a friend.

'Sire,' she said in a tired voice, 'even one under sentence of death has the right to care of a friend. Jason Beaufort was hurt trying to save you and—'

'And in your view, my behaviour is thoroughly ungrateful? Don't worry, Mademoiselle, your American friend is not seriously hurt. A ball in the arm, and I daresay not the first. Captain Trebriant is at this moment looking for the carriage he says he left on the road. After which, he will go quietly back to Paris.'

'In that case, I want to see him!'

Napoleon's fist smashed down on a fragile lemonwood table with such force that it broke beneath the blow.

'Who dares to say "I want" to me! Enough! You will see this man only with my permission and when I think fit! Fouché, since you are so keen on acting as escort, you may see to this Beaufort—'

The Minister of Police bowed and with an ironical glance, accompanied by a discreet shrug of the shoulders, he took leave and withdrew.

She watched him as he went through the door, round-shouldered and beaten. It was a sight that should have given her pleasure but the man whose anger she had just witnessed was too far removed from the charming Charles Denis. She understood now why they called him the Corsican ogre! But, for all her present fury, Marianne could not pretend to herself that she did not like that masterful tone.

Josephine had watched this scene without interfering. But when Fouché had gone she rose and took Marianne's arm where she stood rooted to the spot.

'Obey, child. One must never cross the Emperor – whatever his commands.'

Marianne's eyes, still flaming with revolt, met Josephine's sad, gentle ones. Despite her own love for Napoleon, she could not help feeling drawn to this lonely woman who was so kind to her and seemed to give no thought of the strangeness of her situation. She did her best to smile and then, bending quickly, placed her lips on the pale hand of the dethroned Empress.

'I obey you, madame.'

The Emperor gave no sign of hearing this final piece of defiance. He stood with his back to the two women, staring out of the window and twisting the fringe of a gleaming watered silk curtain nervously between his fingers. Without another word, Marianne dropped a curtsey to Josephine and followed the maid summoned by Queen Hortense. As she went, she wondered if there would ever come a time when she would be able to choose her own clothes and not be obliged to borrow from all and sundry.

Half an hour later, wearing a dress and coat belonging to Madame de Recusant, the former Empress's lady-in-waiting who was more or less the same size as herself, Marianne took her place with drooping head and heavy heart in the Imperial berlin. She was not even conscious of the amazing honour done her. For her, it meant nothing because she cared not whether the ill-humoured little man who sat next to her were Emperor or not. Since he did not love her, she would a hundred times have preferred any stranger. The burning memories of Butard lay between them a source of hideous anguish now, which only increased her pain and wretchedness. The man she loved had changed suddenly into some kind of judge, as icy and indifferent as justice itself. Any fears she might have of the journey which lay ahead were because she knew what power this ruthless man possessed to make her suffer.

"Marianne" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne" друзьям в соцсетях.