'There's no one there. It must have been a rat.'

'Or just the woodwork creaking,' Fortunée added, shivering in her furs. 'It is so dank in here! Are you sure you want to live here, Marianne?'

'Quite sure,' Marianne answered on a note of sudden happiness, 'and the sooner the better. I shall ask the architects to work as quickly as possible! I think they will be here soon.'

For the first time, she had spoken out loud, as though officially taking possession of the silence. The warm notes of her voice rang through the empty rooms triumphantly. She smiled at Fortunée.

'Let's go,' she said. 'You are almost dead with cold. It's as draughty here as in the street.'

'You don't want to see upstairs,' Jolival said. 'I can tell you, there is nothing there. Apart from the walls, which could not be stolen, and the charred remains in the fireplaces, absolutely nothing is left.'

'Then I had rather not see. It is too sad. I want this house to find its soul again—'

She stopped, her eyes on the portrait, with the sensation of having said something foolish. The soul of the house was there, before her, smiling arrogantly against an apocalyptic background. What she had to do was to restore its body, by re-creating the past.

Outside, they could hear the horses blowing and stamping on the cobblestones. The cry of a water carrier rang out, waking the echoes of what had been formerly the rue de Bourbon. It was the voice of life, of the here and now which held so much appeal for Marianne. With Napoleon's love to protect her, she would live here as sole mistress, free to act as she pleased. Free! It was a fine word when, at that very moment, she might have been buried alive in the heart of the English countryside by the will of a tyrannical husband, with boredom and regret her only companions. For the first time, it occurred to her that after all she might have been lucky.

Slipping her arm affectionately through Fortunée's, she walked back with her to the hall, though not without one last affectionate look of farewell at the handsome portrait.

'Come,' she said gaily. 'Let's go and have a big, scalding hot cup of coffee. That's the only thing I really want at present. Close the doors carefully, my friend, won't you?'

The 'Greek prince' grinned. 'Don't worry,' he said. 'It would be too bad if so much as a single draught escaped.'

In a cheerful mood, they left the house, re-entered the carriage and were driven back to Madame Hamelin's.

Charles Percier and Leonard Fontaine might have been called the heavenly twins of decoration under the Empire. For years, they had worked together in such close collaboration that beside them, Castor and Pollux, Orestes and Pylades might have seemed mortal enemies. They had met first in the studios of their common master, Peyre, but then, when Percier won the Grand Prix de Rome in 1785 and Fontaine the second Grand Prix in 1786, they came together again beneath the umbrella pines of the Villa Medici and had remained together ever since. Between them, they had undertaken to re-design Paris in the Napoleonic style, and there was nothing good of Percier's that did not show the hand of Fontaine and no proper Fontaine without a touch of Percier. And being the same age, within a year or two, one born in Paris the other at Pontois, they were generally regarded in every day life as inseparable brethren.

It was this pair, so eminently representative of French art under the Empire who, late that afternoon, stepped through the doors of Fortunée's salon. That salon had never been so empty of company, but since this was Napoleon's wish, that amiable lady uttered no word of protest. Except for Gossec, not a soul had crossed her threshold all that day.

The two architects, after bowing politely to the ladies, gave Marianne to understand that they had paid a preliminary visit to the house in the rue de Lille earlier that afternoon.

'His majesty the Emperor,' Charles Percier added, 'has intimated to us that the work should be so carried out that you, mademoiselle, may take possession of your house with the least possible delay. We have therefore no time to waste. To be sure, the house has suffered a good deal of damage.'

'But we feel,' Fontaine went on, 'that we shall very soon be able to remove all traces of the ravages worked by time and men.'

'We have therefore,' Percier took him up, 'taken the liberty of bringing along with us some designs we happened to have by us, simply one or two ideas sketched for our own pleasure, but which seem perfectly suited to this old house.'

Marianne's eyes, which throughout this well orchestrated dialogue had been swivelling between the two men, from the short Percier to the tall Fontaine, came to rest at last on the roll of papers which the first named was already unrolling on a table. She caught a glimpse of roman style furnishing, Pompeian friezes, alabaster figures, gilded eagles, swans and victories.

'Gentlemen,' she said quietly, taking some pains to stress the slight foreign accent with which she spoke French so as to lend substance to her supposed Venetian origin, 'can you answer me one question?'

'What is that?'

'Are there in existence any plans indicating what the Hôtel d'Asselnat was like before the Revolution?'

The two architects looked at one another with barely concealed alarm. They had known they were to work for an Italian singer, as yet unknown, but destined for great fame, a singer who was quite certainly the Emperor's latest fancy. They were expecting a creature of whims and caprices who might not be easy to please and this start to the interview seemed to prove them right. Percier cleared his throat with a little cough.

'For the outside, no doubt we can find plans, but for the interior – but why should you wish to have these plans, mademoiselle?'

Marianne understood perfectly the meaning behind the question. Why should a daughter of Italy be interested in the original appearance of a house in France? She smiled encouragingly.

'Because I should like my house, as far as possible, restored to the state in which it was before the troubles. All this you have shown me is very fine, very attractive, but it is not what I desire. I want the house to be as it was and nothing more.'

Percier and Fontaine raised their arms to heaven in unison, as though performing a well-drilled ballet.

'In the style of Louis XIV or Louis XV? But, mademoiselle, permit me to remind you that is no longer the fashion,' Fontaine said reproachfully. 'No one has anything like that nowadays, it is quite outdated, not at all the thing. His majesty the Emperor himself—'

'His majesty will wish first and foremost for me to have what I want,' Marianne interrupted sweetly. 'I realize of course that it will not be possible to reconstruct the interior decorations exactly as they were, since we do not know what that was like. But I think it will do very well if you will carry out everything to suit the style of the house and, especially, the portrait which is in the salon.'

There was a silence so complete that Fortunée stirred in her chair.

'The portrait?' said Fontaine. 'Which portrait—'

'But, the portrait of—' Marianne stopped short. She had been on the point of saying: 'The portrait of my father', but the singer Maria Stella could have no connection with the family of d'Asselnat. She drew a deep breath and then continued hurriedly: 'A magnificent portrait of a man which I and my friends saw this morning hanging over the fireplace in the salon. A man dressed in the uniform of an officer of the old king's—'

'Mademoiselle,' the two architects answered in unison, 'I can assure you that we saw no portrait—'

'But, I am not going out of my mind!' Marianne cried losing patience. She could not understand why these two men refused to discuss the portrait. She turned in desperation to Madame Hamelin.

'Oh really, my dear, you saw it too—?'

'Yes,' Fortunée said uneasily, 'I saw it. And do you really say, gentlemen, that there was no portrait in the salon? I can see it now: a very handsome man of noble bearing, wearing a colonel's uniform.'

'We give you our word, madame,' Percier assured her, 'that we saw no portrait. Had it been otherwise we should certainly have mentioned it at once. A single portrait left in a devastated house would have been remarkable enough!'

'And yet it was there,' Marianne persisted stubbornly.

'It was there, certainly.' Jolival's voice spoke from behind her. 'But just as certainly, it is not there now.'

Arcadius had been missing all afternoon but now, as he walked farther into the room, Percier and Fontaine, who had been beginning to wonder if they had fallen among lunatics, breathed again and turned gratefully to this unlooked for rescuer. But Arcadius, as amiable and unconcerned as ever, was kissing the fingers of the mistress of the house and Marianne.

'We can only imagine someone has taken it,' he remarked lightly. 'Well, gentlemen, have you reached an agreement with the – signorina Maria Stella—'

'Er – that is – not yet. This business of the portrait—'

'Forget it,' Marianne said tersely. She had realized that Jolival did not wish to speak of it before strangers. Now, much as she had liked these two in the beginning, she had only one wish, to see the back of them and be left alone with her friends. With this view, she forced herself to smile and say lightly but firmly:

'Remember only one thing. That my desire to see the house look as it used to do remains unaltered.'

'In the style of the last century?' Fontaine murmured with comical dismay. 'Are you quite determined on that?'

'Quite determined. I want nothing else. Do your best to make the Hôtel d'Asselnat look as it used to do, gentlemen, and I shall be eternally grateful to you.'

There was nothing more to add. The two men withdrew, assuring her they would do their best. Barely hail they gone downstairs before Marianne fell on Arcadius.

'My father's portrait, what do you know about it?'

'That it is no longer where we saw it, my poor child. I went back to the rue de Lille without saying anything to you, after the architects had gone in fact, I watched them leave, I wanted to go over the house from top to bottom because there were a number of things which struck me as odd, those well oiled locks among other things. It was then I noticed that the portrait had disappeared.'

'But, then what can have happened to it? This is ridiculous! It's unbelievable!'

Marianne was bitterly disappointed. It seemed to her that now she had really lost the father she had never known and had discovered that morning with such joy. This sudden disappearance was very cruel.

'I should not have left it. I was so incredibly lucky to find it, I should have taken it with me, at once. But how could I have guessed that someone would come and move it. For that must be what happened, surely? It has been stolen!'

She was walking up and down the room unhappily as she spoke, wringing her hands together. Arcadius, though outwardly calm, never took his eyes off her.

'Stolen? Perhaps—'

'What do you mean, perhaps?'

'Don't be cross. I am merely thinking that whoever put it in the salon has simply taken it away again. You see, instead of trying to find out who took the portrait, I think we should do better to try and find out who put it there in the midst of all that wreckage. Because it is my belief that when we know that, we shall also know who has the portrait now.'

Marianne said nothing. What Jolival said was true. Instead of grieving, she began to think. She remembered the brightness of the canvas and the frame, how meticulously clean they were in contrast to the squalor around them. There was some mystery there.

'Would you like me to inform the Minister of Police?' Fortunée suggested. 'He will make inquiries, discreet ones if you like, but I'll be prepared to swear that he will find your portrait before very long.'

'No – thank you, I would rather not.'

What, above all, she would rather not see was the astute Fouché dabbling in something which concerned her so closely. She felt that by putting Fouché's men with their dirty fingers on the trail of her father's disappearing image, she would be in some way soiling the beauty of that image which she had so briefly recovered.

'No—' she said again, 'truly I would rather not.' She added: 'I prefer to try and find out myself.'

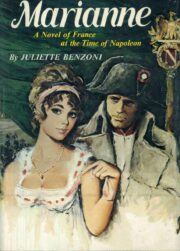

"Marianne" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne" друзьям в соцсетях.