In that moment her mind was made up.

'Jolival, my dear,' she said calmly, 'tonight, we will go back to the rue de Lille, as unobtrusively as possible.'

'Go back to the rue de Lille tonight,' Fortunée protested. 'You cannot mean it? What for?'

'It would seem that there is a ghost in the old house. Don't ghosts prefer the night time?'

'You think someone comes there?'

'Or hides there.'

An idea was growing in her mind as she spoke. Or rather, a memory which was becoming clearer with every moment. Of a few remarks she had heard as a child. More than once, Aunt Ellis had told her of her adventures as a tiny baby, how the abbé de Chazay had found her, left all alone in the house after her parents had been taken away. At that time, the abbé himself had been living in the rue de Lille, in one of those secret hiding places which had been constructed in a great many aristocratic houses in town and country to hide refractory priests. 'That must be it!' she said, finishing her thoughts aloud, 'someone must be hiding in the house.'

'It is impossible,' Jolival answered. 'I have been everywhere, I tell you, from top to bottom.'

But he listened very attentively when she told him the story of the abbé de Chazay. Unfortunately, she did not know where this hiding place lay. It might be in the cellars, the attic or behind the panelling in one of the rooms. The abbé himself, whether intentionally or from sheer absentmindedness, had never told her precisely.

'In that case, we may search for a very long time. Some of these hiding places were completely impossible to discover, except by a stroke of luck. We shall have to sound out the walls and ceilings.'

'At all events, no one could live long in one of those hiding places without outside help,' Marianne said. 'They would need food and fresh air and all the other necessities of life.'

Fortunée, who was lying on a blue watered-silk chaise longue, sighed and stretched, then began rearranging the folds of her red cashmere gown, yawning widely as she did so.

'You don't think perhaps you two are romancing a little?' she said. 'I think the house has been empty for so long that some poor homeless wretch must have been living in it, and our going in like that, followed by the architects, must have disturbed him, that is all.'

'And the portrait?' Marianne said seriously.

'He must have found it in the house, perhaps in the attics or hidden away in some odd corner, which would explain why it escaped when everything else was wrecked. Because it was the only pretty thing left, he used it to adorn his desert and when we invaded his domain today he simply went away and took with him what he had come to regard as his own property. I sincerely believe, Marianne, that if you want to get your picture back the only sensible thing to do is to tell Fouché. It can't be easy to wander about Paris with a canvas that size under one's arm. Would you like me to send for him? We are reasonably good friends.'

It began to look as though the charming Fortunée had good friends everywhere, but once again, Marianne refused. Against all the evidence, some instinct was telling her that there was some other explanation, and that the eminently simple and rational theory put forward by her friend was not the right one. She had been conscious of a presence in the house, which she had at first put down to the magnetic power of the portrait, but now she realized that there was something else. She recalled the footfalls they had heard upstairs. Arcadius had decided it must have been a rat, but was it? She could not help thinking that there was some mystery about her ancestral home and she meant to get to the bottom of it, but she would do so alone. Or at least, with only Arcadius to help her. She turned to him now.

'I mean what I said. Will you come with me tonight and see what is going on in my house?'

'Why ask?' Jolival shrugged. 'For one thing, not for anything in the world could I allow you to go alone into that morgue, but for another – I must admit that this peculiar business intrigues me too. We'll leave here at ten o'clock, if that suits you.'

Fortunée sighed. 'And much good may it do you! My dear child, you do seem to be inordinately fond of adventures. For myself, I shall stay quietly at home, with your permission. Firstly because I have not the slightest desire to go and freeze to death in an empty house, and secondly because someone must be here to warn the Emperor in case you are running into another of those traps you seem to have a knack of finding. And I dread to think what he will do to me if anything should happen to you!' she finished with comical alarm.

The remainder of the evening passed in supping and afterwards in making ready for the intended expedition. For a moment, it did occur to Marianne to think of the mysterious danger against which Jason Beaufort had warned her but she rejected the idea at once. Why should she expect any danger? Surely no one could have foreseen that Napoleon would give her back the house which had been her parent's? No, the Hôtel d'Asselnat could be in no way connected with the American's fears.

But Marianne was not fated to go adventuring with Arcadius that night. The clock had just struck a quarter to ten and she had already risen from her chair to go and put on some more suitable clothes for what lay ahead, when Fortunée's black servant Jonas appeared to announce with his invariable solemnity that 'Monsigneur le duc de Frioul' requested admittance. Absorbed in their own conversation, neither Marianne, nor Fortunée, nor Arcadius had heard the carriage arrive. They gazed at one another blankly but Fortunée recovered herself at once.

'Show him in,' she said to Jonas. 'The dear duke must be bringing word from the Tuileries.'

The Grand Marshal of the palace was doing better than that.

Hardly had he entered the room and kissed Fortunée's hand before he said gaily to Marianne:

'I come in search of you, mademoiselle. The Emperor is asking for you.'

'Truly? Oh, I am coming, I am coming at once—'

She was so happy to be going to him that evening when she had been given no reason to hope for it, that for a second she forgot the business of the missing picture. In her haste to go to Napoleon, she hurried away to put on a pretty dress of green velvet braided with silver with a deeply scooped out neckline and short sleeves trimmed with a froth of lace, snatched up a pair of long white gloves and flung on a great cloak of the same velvet, cut like a flowing domino with a hood trimmed with grey fox. She loved these things and blew a kiss with her fingertips at the radiantly joyful reflection in her mirror before running down to the salon where Duroc was calmly drinking coffee with Fortunée and Arcadius. He was talking at the same time and, as he was talking about the Emperor, Marianne paused in the doorway to listen to the end of what he was saying.

'—and when he had seen the finished column in the place Vendôme, the Emperor went on to inspect the Ourcq Canal. He is never still for a moment!'

'Was he pleased?' Madame Hamelin asked.

'With these works, yes, but the war in Spain remains his greatest anxiety. Things are going badly there. The men are sick, the Emperor's brother, King Joseph, lacks imagination, the marshals are weary and jealous of one another, while the guerilleros harry the army and are helped by the local population, who are both hostile and cruel. And then Wellington's English are firmly established in the country.'

'How many men have we there?' Arcadius asked in a grave voice.

'Nearly eighty thousand. Soult has replaced Jourdan as Major General. King Joseph has Sebastiani, Victor and Mortier under him, while Suchet and Augereau are occupying Aragon and Catalonia. At this moment, Massena and Junot are joining forces with Ney and Montbrun ready to march into Portugal—'

Marianne's entry cut short Duroc's military disquisition. He looked up, smiled and set down his empty cup.

'Let us go, then, if you are ready. If I let myself be drawn into army talk we shall be here all night.'

'All the same, I wish you could go on! It was very interesting.'

'Not for two pretty women. Besides, the Emperor does not like to be kept waiting.'

Marianne felt a brief stab of remorse when she met Jolival's eye and remembered their planned expedition. But after all, there was no danger in the house.

'Another time,' she told him with a smile. 'I am ready, my lord duke.'

Jolival gave her a sidelong smile while continuing to stir the spoon gravely in his blue Sevres cup.

'But of course,' he said. 'There is no hurry.'

When the impassive Rustan opened the door of the Emperor's office for Marianne, Napoleon was sitting working at his big desk and did not look up, even when the door was shut. Marianne looked at him in astonishment, uncertain how she should react. The wind was completely taken out of her sails. She had come to him in happy haste, borne up on the wave of joy which the mere thought of her lover awoke in her. She had thought to find him in his own room, or at least waiting for her impatiently. She came, expecting to throw herself into arms wide open to receive her. She had come, in short, hurrying to meet the man she loved – and found the Emperor.

Hiding her disappointment as best she could, she let her knees give and, sinking into a deep curtsey, waited with bent head.

'Get up and sit down, mademoiselle. I will be with you in a moment.'

Oh, that terse, cold, impersonal voice. Marianne's heart contracted as she moved to sit down on the little yellow sofa placed in front of the desk at right angles to the fire where she had seen Fortunée for the first time. There, she sat quite still, not daring to move, practically holding her breath. The silence was so complete that the swift scratching of the imperial pen across the paper seemed to her to make a shattering noise. Napoleon went on writing, eyes down, amid an improbable pile of red folders, open and closed. The room was strewn with papers. A sheaf of rolled up maps stood in a corner. For the first time, Marianne saw him in uniform. For the first time, the thought came to her of the vast armies he commanded.

He was wearing his favourite olive green uniform of a colonel of the chasseur of the Guard but instead of the high uniform boots he wore white silk stockings and silver buckled shoes. As usual, his white Kerseymere breeches were ink stained and showed the marks of his pen. Across his white waistcoat lay the purple ribbon of the Legion d'Honneur, but what struck Marianne most of all were the locks of short brown hair plastered to his forehead by beads of sweat from the heat with which he worked. In spite of her disappointment, in spite of her vague feeling of anxiety, she was suddenly overwhelmed by a warm rush of tenderness. She was suddenly so sharply conscious of her love that she had to make an effort not to throw her arms about his neck. But, certainly an emperor was not a man like any other. The impulses which would have been so sweet and natural with an ordinary mortal, must be mastered until it suited his pleasure. No, Marianne thought with childish regret, truly it was not easy to love one of the giants of history.

Suddenly, the 'giant' threw down his pen and looked up. The eyes that met hers were as cold as steel.

'So, mademoiselle,' he said abruptly, 'it seems you dislike the style of my times? From what I hear, you wish to revert to the splendours of the past century?'

For a moment, surprise left her speechless. This was the last thing she had been expecting. But anger soon restored her voice. Did Napoleon, by any chance, mean to dictate every single act of her life, even her likes and dislikes? All the same, well knowing it was dangerous to cross swords with him, she forced herself to be calm and even managed to smile. After all, it was rather funny. Here she came running to him, all throbbing with love, and he was talking about decoration. The thing that seemed to vex him most was her apparent lack of enthusiasm for the style he had adopted as his own.

'I have never said I did not like your style, sire,' she said sweetly. 'I merely expressed a wish that the Hôtel d'Asselnat should look once more as it used to do—'

'What makes you think that when I gave it to you I desired such a resurrection? The house I gave you must be that of a famous Italian singer, belonging wholly to the present regime. There can be no question of turning it into a temple for your ancestors. Do you forget that you are no longer Marianne d'Asselnat?'

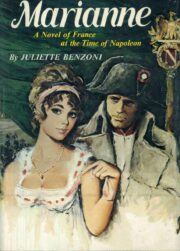

"Marianne" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne" друзьям в соцсетях.