After shaking hands with the Macgregors, Royce cast her a glance, then retrieved Sword and mounted. She urged Rangonel alongside as he turned down the track.

At the last, she waved to the Macgregors. Still beaming, they waved back. Facing forward, she glanced at Royce. “Am I allowed to say I’m impressed?”

He grunted.

Smiling, she followed him back to the castle.

“Damn it!” With the sounds of a London evening-the rattle of wheels, the clop of hooves, the raucous cries of jarveys as they tacked down fashionable Jermyn Street-filling his ears, he read the short note again, then reached for the brandy his man had fortuitously just set on the table by his elbow.

He took a long swallow, read the note again, then tossed it on the table. “The duke’s dead. I’ll have to go north to attend his funeral.”

There was no help for it; if he didn’t appear, his absence would be noted. But he was far from thrilled by the prospect. Until that moment, his survival plan had revolved around total and complete avoidance, but a ducal funeral in the family eradicated that option.

The duke was dead. More to the point, his nemesis was now the tenth Duke of Wolverstone.

It would have happened sometime, but why the hell now? Royce had barely shaken the dust of Whitehall from his elegantly shod heels-he certainly wouldn’t have forgotten the one traitor he’d failed to bring to justice.

He swore, let his head fall back against the chair. He’d always assumed time-the simple passage of it-would be his salvation. That it would dull Royce’s memories, his drive, distract him with other things.

Then again…

Straightening, he took another sip of brandy. Perhaps having a dukedom to manage-one unexpectedly thrust upon him immediately following an exile of sixteen years-was precisely the distraction Royce needed to drag and hold his attention from his past.

Royce had always had power; his inheriting the title changed little in that regard.

Perhaps this really was for the best?

Time, as ever, would tell, but, unexpectedly, that time was here.

He thought, considered; in the end he had no choice.

“Smith! Pack my bags. I have to go to Wolverstone.”

In the breakfast parlor the following morning, Royce was enjoying his second cup of coffee and idly scanning the latest news sheet when Margaret and Aurelia walked in.

They were gowned, coiffed. With vague smiles in his direction, they headed for the sideboard.

He glanced at the clock on the mantelpiece, confirming it was early, not precisely the crack of dawn, yet for them…

His cynicism grew as they came to the table, plates in hand. He was at the head of the table; leaving one place empty to either side of him, Margaret sat on his left, Aurelia on his right.

He took another sip of coffee, and kept his attention on the news sheet, certain he’d learn what they wanted sooner rather than later.

His father’s four sisters and their husbands, and his mother’s brothers and their wives, together with various cousins, had started arriving yesterday; the influx would continue for several days. And once the family was in residence, the connections and friends invited to stay at the castle for the funeral would start to roll in; his staff would be busy for the next week.

Luckily, the keep itself was reserved for immediate family; not even his paternal aunts had rooms in the central wing. This breakfast parlor, too, on the ground floor of the keep, was family only, giving him a modicum of privacy, an area of relative calm in the center of the storm.

Margaret and Aurelia sipped their tea and nibbled slices of dry toast. They chatted about their children, their intention presumably to inform him of the existence of his nephews and nieces. He studiously kept his gaze on the news sheet. Eventually his sisters accepted that, after sixteen years of not knowing, he was unlikely to develop an interest in that direction overnight.

Even without looking, he sensed the glance they exchanged, heard Margaret draw in one of her portentous breaths.

His chatelaine breezed in. “Good morning, Margaret, Aurelia.” Her tone suggested she was surprised to find them down so early.

Her entrance threw his sisters off-balance; they murmured good mornings, then fell silent.

With his eyes, he tracked Minerva to the sideboard, taking in her plain green gown. Trevor had reported that on Saturday mornings she eschewed riding in favor of taking a turn about the gardens with the head gardener in tow.

Royce returned his gaze to the news sheet, ignoring the part of him that whispered, “A pity.” He wasn’t entirely pleased with her; it was just as well that when he rode out shortly, he wouldn’t come upon her riding his hills and dales, so he wouldn’t be able to join her, her and him alone, private in the wild.

Such an encounter would do nothing to ease his all but constant pain.

As Minerva took her seat farther down the board, Margaret cleared her throat and turned to him. “We’d wondered, Royce, whether you had any particular thoughts about a lady who might fill the position of your duchess.”

He held still for an instant, then lowered the news sheet, looked first at Margaret, then at Aurelia. He’d never gaped in his life, but…“Our father isn’t even in the ground, and you’re talking about my wedding?”

He glanced at his chatelaine. She had her head down, her gaze fixed on her plate.

“You’ll have to think of the matter sooner rather than later.” Margaret set down her fork. “The ton isn’t going to let the most eligible duke in England simply”-she gestured-“be!”

“The ton won’t have any choice. I have no immediate plans to marry.”

Aurelia leaned closer. “But Royce-”

“If you’ll excuse me”-he stood, tossing the news sheet and his napkin on the table-“I’m going riding.” His tone made it clear there was no question involved.

He strode down the table, glanced at Minerva as he went past.

He halted; when she looked up, he caught her autumn eyes. His own narrow, he pointed at her. “I’ll see you in the study when I get back.”

When he’d ridden far enough, hard enough, to get the tempest of anger and lust roiling through him under control.

Striding out, he headed for the stables.

By lunchtime on Sunday he was ready to throttle his elder sisters, his aunts, and his aunts-by-marriage, all of whom had, it seemed, not a thought with which to occupy their heads other than who-which lady-would be most suitable as his bride.

As the next Duchess of Wolverstone.

He’d breakfasted at dawn to avoid them. Now, in the wake of the ruthlessly cutting comments he’d made the previous night, silencing all such talk about the dinner table, they’d conceived the happy notion of discussing ladies, who all just happened to be young, well-bred, and eligible, comparing their attributes, weighing their fortunes and connections, apparently in the misguided belief that by omitting the words “Royce,” “marriage,” and “duchess from their comments, they would avoid baiting his temper.

He was very, very close to losing it-and inching ever closer by the second.

What were they thinking? Minerva couldn’t conceive what Margaret, Aurelia, and Royce’s aunts hoped to achieve-other than a blistering set-down which looked set to be delivered in a thunderous roar at any minute.

If one were possessed of half a brain, one did not provoke male Variseys. Not beyond the point where they grew totally silent, and their faces set like stone, and-the final warning-their fingers tightened on whatever they were holding until their knuckles went white.

Royce’s right hand was clenched about his knife so tightly all four knuckles gleamed.

She had to do something-not that his female relatives deserved saving. If it were up to her, she’d let him savage them, but…she had two deathbed vows to honor, which meant she had to see him wed-and his misbegotten relatives were turning the subject of his marriage into one he was on the very brink of declaring unmentionable in his hearing.

He could do that-and would-and would expect and insist and ensure he was obeyed.

Which would make her task all the harder.

They seemed to have forgotten who he was-that he was Wolverstone.

She glanced around; she needed help to derail the conversation.

There wasn’t much help to be had. Most of the men had escaped, taking guns and dogs and heading out for some early shooting. Susannah was there; seated on Royce’s right, she was wisely holding her tongue and not contributing to her brother’s ire in any way.

Unfortunately, she was too far from Minerva’s position halfway down the board to be easily enlisted; Minerva couldn’t catch her eye.

The only other potential conspirator was Hubert, seated opposite Minerva. She had no high opinion of Hubert’s intelligence, but she was desperate. Leaning forward, she caught his eye. “Did you say you’d seen Princess Charlotte and Prince Leopold in London?”

The princess was the darling of England; her recent marriage to Prince Leopold was the only topic Minerva could think of that might trump the subject of Royce’s bride. She’d imbued her question with every ounce of breathless interest she could muster-and was rewarded with instant silence.

Every head swung to the middle of the table, every female pair of eyes followed her gaze to Hubert.

He stared at her, eyes showing the surprise of a startled rabbit. Silently she willed him to reply in the affirmative; he blinked, then smiled. “I did, as a matter of fact.”

“Where?” He was lying-she could see he was-but he was willing to dance to her tune.

“In Bond Street.”

“At one of the jewelers?”

Slowly, he nodded. “Aspreys.”

Royce’s aunt Emma, seated next to Minerva, leaned forward. “Did you see what they were looking at?”

“They spent quite a bit of time looking at brooches. I saw the attendant bring out a tray-on it were-”

Minerva sat back, a vacuous smile on her face, and let Hubert run on. He was well-launched, and with a wife like Susannah, his knowledge of the jewelry to be found in Aspreys was extensive.

All attention had swung to him.

Leaving Royce to finish his meal without further aggravation; he needed no encouragement to apply himself to the task.

Hubert had only just passed on to the necklaces the royal couple had supposedly examined when Royce pushed away his plate, waved Retford’s offer of the fruit bowl aside, dropped his napkin beside his plate, and stood.

The movement broke Hubert’s spell. All attention swung to Royce.

He didn’t bother to smile. “If you’ll excuse me, ladies, I have a dukedom to run.” He started striding down the room on his way to the door. Over the heads, he nodded to Hubert. “Do carry on.”

Drawing level, his gaze pinned Minerva. “I’ll see you in the study when you’re free.”

She was free now. As Royce strode from the room, she patted her lips, edged back her chair, waited for the footman to draw it out for her. She smiled at Hubert as she stood. “I know I’ll regret not hearing the rest of your news-it’s like a fairy tale.”

He grinned. “Never mind. There’s not much more to tell.”

She swallowed a laugh, fought to look suitably disappointed as she hurried from the room in Royce’s wake.

He’d already disappeared up the stairs; she climbed them, then walked quickly to the study, wondering which part of the estate he’d choose to interrogate her on today.

Since their visit to Usway Burn on Friday, he’d had her sitting before his desk for a few hours each day, telling him about the estate’s tenant farms and the families who held them. He didn’t ask about profits, crops, or yields, none of the things Kelso or Falwell were responsible for, but about the farms themselves, the land, the farmers and their wives, their children. Who interacted with whom, the human dynamics of the estate; that was what he questioned her on.

When she’d passed on his father’s dying message, she hadn’t known whether he’d actually had it in him to be different; Variseys tended to breed true, and along with their other principal traits, their stubbornness was legendary.

That was why she hadn’t delivered the message immediately. She’d wanted Royce to see and know what his father had meant, rather than just hear the words. Words out of context were too easy to dismiss, to forget, to ignore.

But now he’d heard them, absorbed them, and made the effort, responded to the need, and scripted a new way forward with the Macgregors. She was too wise to comment, not even to encourage; he’d waited for her to say something, but she’d stepped back and left him to define his own way.

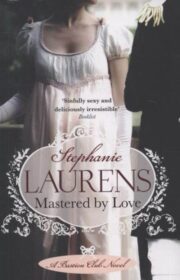

"Mastered By Love" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mastered By Love". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mastered By Love" друзьям в соцсетях.