They were together on the island. They came down to the shore; the man hi the toga was doing something to the boat They were going to row back.

Anger constricted my throat. I would wait for them. I would be there when the boat touched the sand.

But no … they were not coming back. They had been making sure that the boat was securely tied. Once before they had not tied it securely enough.

I thought: I will go over. I will confront them. This time he’ll not find me cowering under a dust sheet.

I was untying the boat when I heard a cry from behind me.

“Stop, Miss.”

Fanny was running down the cliff path and came panting to stand beside me.

“What are you doing here? You were going to get into that boat!”

“I had a fancy to go out to the island.”

“Are you mad? On a night like this, with the sea choppy! If that boat overturned you’d be dragged down in those skirts before you could say Jack Robinson.”

She was right.

“Oh I know,” she went on grimly, “I saw. But it’s not for you to go over there. Now you’d better get back to that ball and forget about it.”

“Not just yet, Fanny. I want to stay out here for a while.”

“It’s too chilly. Come on.”

We climbed up to one of the arbors, and there we sat together for a while.

Fanny looked fierce. I wanted to talk to her but I daren’t I was trying to pretend that I had imagined I had seen them on the island.

At length we returned. I didn't see Bevil and Jessica again until the unmasking. Then they were not together.

It was the early hours of the morning before the last guests had gone and I was alone with Bevil. I kept on my dress to give me confidence. I was going to speak to him because I couldn’t remain in suspense.

I gripped my hands behind my back to give me courage. He was humming one of the waltz tunes and, coming to me, put his arms about me and tried to dance round the room with me.

“I think our ball was a success,” he said. “We must do more entertaining.”

There’s something I have to say to you, Bevil.”

He stopped and looked at me intently, noticing the gravity of my voice.

“I left the ballroom at one time,” I said. “I went down to the beach and saw two people on the island.”

He raised his eyebrows. “You mean—our guests?”

“One of them was Jessica Trelarken. The other was in a Roman toga.”

“The Romans were ubiquitous tonight” He spoke lightly.

“Bevil,” I said, “was it you?”

He looked startled; he hesitated, and my heart leaped with fear.

“On the island? Certainly not!”

I thought: Would it be part of his code to lie, to defend his mistress in any way necessary?

“I thought…”

“I know what you thought Because of that unfortunate affair of the teddy bear …”

“You really weren’t there, Bevil?”

“I really wasn't there,” he replied, mimicking my earnest tone.

Then he took the snood from my hair and threw it onto the dressing table. His hands were on my dress.

“How does this thing unfasten?” he asked.

I turned my back to show him. I believed him—because I wanted to so much.

A few weeks later Bevil had to go to London, and I went with him. Although I loved Menfreya so much, I was delighted to get away from Jessica.

I was very happy in Bevil's little town house; I met many of his political friends, and because I was able to talk to them about politics and the party I was a great success and Bevil was proud of me.

“Of course,” they said, “as Sir Edward’s daughter you knew all about it before you married.” They thought Bevil had made a very wise marriage; they envied him, they said; and he liked to be envied.

I enjoyed calling on Aunt Clarissa. Phyllis was engaged, but the match was not up to their expectations. I was sorry for Sylvia, who was still unattached. But I couldn’t help being amused at the different treatment accorded my new status. Aunt Clarissa rather implied that I owed my good fortune to her endeavors. Bevil and I laughed a great deal about this when we were alone.

Yes, they were happy days.

It was while we were in London that I had the idea of turning the island house into a holiday home for poor children who had no opportunity of having a few weeks by the sea in summer. This notion had come to me when I had made a sentimental journey to the markets I had long ago visited with Fanny. I saw them through different eyes now and longed to give those little coster children a taste of sea air.

I was excited by the project and delighted when Bevil agreed with me that it would be a fine way of using the house which had been so useless. I decided that as soon as I returned I would make preparations, and it might be that we could start our holiday scheme at the beginning of the following summer.

By the time we returned Jo Menfreya the autumn was well advanced. Benedict was pleased to see us and found primroses in the lane which he brought to me. They were a rarity at this time of the year, but I have seen them occasionally in November, as though the balminess of the weather has deluded them into thinking that the spring had come. “For you,” he told me; and I was delighted until I realized that Jessica had prompted him to make the offering. I sometimes had the notion that she was trying to placate me.

It was soon after our return that the rumor about the island became the prevailing topic for several days.

Two of the local girls, out after dusk, hurrying along the cliff path, were sure they saw a ghost on the island. According to their account, they had both seen the apparition, had looked at each other and then started to run home as fast as they could.

They were questioned by then? parents. “A ghost? What did it look like?’

“Like a man.”

Then perhaps it was a man.”

” Twas no man, we know.”

“Then how did ‘ee know ‘twas a ghost?”

“We did know, didn't us, Jen?”

“Yes, we did know.”

“But how?”

“ Twere the way he stood there.”

“How do ghosts stand?”

“I dunno. But ‘tain’t like ordinary folk. Looking to Menfreya he was …”

“How?”

“How ghosts do.”

“How’s that?”

“I dunno. You just know it’s how they be when you do see un, don’t see, Jen?”

“Aye, you do just know.”

“I wouldn’t live hi that house for a farm.”

So the story went round. A man had appeared on the island, and although it wasn’t possible to see him clearly they knew he wasn’t any man of the neighborhood. He wasn’t anyone they had seen before.

Bevil laughed at the story. “It means they’re running short of scandal. They must have something to talk about.”

But I thought of the night when I had hidden under the dust sheets; I thought of the night of the ball. I had seen two of our guests there then. Could it be that they had found the island house a pleasant meeting place? Could it be that the man who had been there that night was the “ghost” seen by the two girls.

I wondered.

The Cornish people love a ghost There are more ghosts in Cornwall than in all the rest of England; they can be piskies, knackers, little people, spriggans—but they are ghosts, all the same; and when the Cornish discover one they don’t let him go lightly.

The cliff path was often deserted after dark, but several people claimed to have seen the spirit of the island. He varied from a knacker to a man hi a sugarloaf hat, small but lit by a phosphorescent light so that he could be clearly seen; he was tall beyond ordinary men, some said, and they saw horns sticking out of his head. To others he was an ordinary man in a southwester—a man who had been “returned by the sea.”

I used to sit at my window, looking out to the island, and I could understand how these fantasies were created. The shifting light could play tricks, and with the help of the imagination and absolute belief, almost any image that was desired could be created.

One old man, Jemmie Tomrit, who lived in a two-room cottage in Menfrey stow, was deeply affected by the story. He was a fisherman of ninety—a man respected for his longevity; he was the pride of his family, who were determined to keep him alive till he was at least a hundred. He was a mascot, a talisman. There was a saying in the town: “As long-lived as the Trekellers.” And old Jim Trekeller had lived to ninety-two, his brother to eighty-nine. So the Tomrits were hoping to nave the name Trekeller changed to Tomrit, if they could manage it.

Therefore, the old man was never allowed out in a cold wind; he was cosseted and cared for, and when he was missing from home there was a general outcry.

He was found sitting on the cliff, close to Menfreya, “looking for the ghostie,” he said.

And the Tomrits were angry with Jen and Mabel, who had come home with tales of ghosts on the island, because the old man was always trying to get out to the cliffs to stare at the island. He muttered to himself and hadn’t been the same since; and when he had tried to get out of bed at night and had fallen and bruised himself, the Tomrits had called in Dr. Syms, who had said it was a lucky escape, for it might have been a broken thigh which could have been dangerous at his age. And if he was getting an obsession about the island, well they must remember that he was a very old man and old men must be expected to ramble on a bit—it was called senility.

“Grandfer senile!” cried the Tomrits. ” Tis they silly girls that be responsible for this, Tis a lot of silly nonsense. There would be no ghost on No Man’s Island.”

Then the most important topic hi Menfrey stow was “Would the Tomrits be able to snatch the title from the Trekellers, after all”; and the island ghost slipped into second place, and after a while was only mentioned now and then, although it was remembered at dusk when people found themselves on the lonely cliff path.

I caught a bad cold during November, and Fanny insisted that I spend a few days in bed. She made me her special brew of lemon and barley water, which stood by my bed in a glass jug over which she put a piece of muslin, weighted with beads at the four corners to keep out the dust.

I had to admit it was soothing.

Bevil had to go back to London, and I was sorry I couldn’t accompany him. So, he said, was he; but he thought he would not be away for more than a week or so.

The weather turned stormy and my cold had left me with a cough over which Fanny shook her head and scolded me.

“It’s wise to stay in, dear,” said Lady Menfrey, “until the gales die down. Going out in this weather’s no good for anybody.”

So I stayed hi my room, reading, going through letters which had come to the Lansella chambers and answering some of them. William told me that he was carrying on at the chambers in Lansella while Bevil was away, and it came out that Jessica was helping him.

I was astonished.

“But what of Benedict?”

“His grandmother takes charge of him while she’s away. She’s glad to, and I need help at the chambers. Miss Trelarken has an aptitude for the work, and the people seem to like her.”

Occasionally during those days a feeling of dread would come over me. I felt threatened, but I could not be sure from which direction.

Fanny was aware of it Sometimes I would see her sitting at the window staring broodingly across at the island as though she hoped to find the answer there. I wanted to talk to Fanny, but I dared not Already she hated Bevil; I could not tell her of my vague fears; but her attitude did not help me.

I woke up one night with sweat on my face, startled out of my sleep. I heard myself calling out, though I did not know to whom.

Something was wrong … terribly wrong. Then I knew. I was in pain and I felt sick.

“Bevil,” I called, and then I remembered that he was in London.

I got up and staggered through to Fanny’s room, which was just across the corridor.

“Fanny!” I cried. “Fanny!”

She started up from her bed. “Why, lord save us, what’s the matter?”

“I feel ill,” I told her.

“Here!” She was at my side. She was wrapping something round my shivering body. She got me into bed and sat by me.

After a while I felt better. I stayed in Fanny’s room, and although next morning I no longer felt ill, I was weak and exhausted.

Fanny wanted to send for the doctor, but I said no, I was all right now.

It was just weakness after the cold, Fanny said; but if I felt like that again she was going to have no more nonsense.

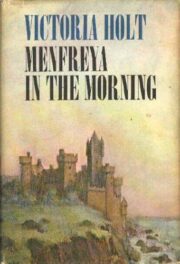

"Menfreya in the Morning" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Menfreya in the Morning". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Menfreya in the Morning" друзьям в соцсетях.