‘You could be pretty,’ Dandy said. Her round pink face appeared beside mine. ‘You could be really pretty,’ she said encouragingly, ‘if you weren’t so odd-looking. If you smiled at the boys a bit.’

I stepped back from the little bit of mirror.

‘They’ve got nothing I want,’ I said. ‘Nothing to smile for.’

Dandy licked her fingers to make them damp and twirled her fringe and the ringlets at the side of her face.

‘What do you want then?’ she said idly. ‘What d’you want that a boy can’t give you?’

‘I want Wide,’ I said instantly.

She turned and stared at me. ‘You’re going to have a silk shirt and breeches, aye and a riding habit, and you still dream of that?’ she asked in amazement. ‘We’ve got away from Da, and we can earn a penny a day, and we eat so well, and we can wear clothes as fine as Quality and everyone looks at us. Everyone! Every girl wishes she could wear velvets like me! And you still think of that old stuff?’

‘’Tisn’t old stuff!’ I said, passionate. ‘’Tisn’t old stuff. It’s a secret. You were glad enough to hear about it when there was just you and me against Da and Zima. I don’t break faith just because I’ve got a place in service.’

‘Service!’ Dandy spat. ‘Don’t call this service. I dress as fine as Quality in my costume!’

‘It’s costume,’ I said angrily. ‘Only a silly Rom slut like you would think it was as fine as Quality, Dandy. You look at real ladies, they don’t wear gilt and dyed feathers like you. The real ones dress in fine silks, cloth so good it stands stiff on its own. They don’t wear ten gilt bangles, they wear one bracelet of real gold. Their clothes ain’t dirty. They keep their voices quiet. They’re nothing like us, nothing like us at all.’

Dandy sprang at me, quicker than I could fend her off. Her two hands were stretched into claws and she went straight for my eyes, and raked a scratch down my cheek. I was stronger than her, but she had the advantage of being heavier – and she was as angry as a scalded cat.

‘I am as good as Quality,’ she said, and pulled at my cap. It was pinned to my hair and the sharp pain as some hair came out made me shriek in pain and blindly strike back at her. I had made a fist, as instinctive as her scratching hands, and I caught her on the jaw with a satisfying thud and she reeled backwards.

‘Meridon, you cow!’ she bawled at me and came for me at a half run and bowled me back on to my straw mattress and sat, with her heavier weight, while I wriggled and tossed beneath her.

Then I lay still. ‘Oh, what’s the use?’ I said wearily. She released me and stood up and went at once to the mirror to see if I had bruised her flower-white skin. I sat up and put a hand to my cheek. It stung. She had drawn blood. ‘We’ve always seen different,’ I said sadly, looking at her across the little room. ‘You thought you might marry Quality from that dirty little wagon with Da and Zima. Now you think you’re as good as Quality because you’re a caller for a travelling show. You might be right, Dandy, it’s just never seemed that wonderful to me.’

She looked at me over her shoulder, her pink mouth a perfect rosebud of discontent. ‘I shall have great opportunities,’ she said stubbornly, stumbling over one of Robert’s words. ‘I shall take my pick when I am ready. When I am Mademoiselle Dandy on the flying trapeze I will have more than enough offers. Jack himself will come to my beck then.’

I put my hand to my head and brought it down wet with blood. I unpinned my cap hoping it was still clean, but it was marked. I would have complained, but what Dandy said made me hold my peace.

‘I thought you’d given up on Jack,’ I said cautiously. ‘You know what his da plans for him.’

Dandy primped her fringe again. ‘I know you thought that,’ she said smugly. ‘And so does his da. And so probably does he. But now I’ve seen what he’s worth, I think I’ll have him.’

‘Have to catch him first,’ I said. I was deliberately guarding myself against the panic which was rising in me. Dandy was wilfully blind to the tyrannical power of Robert Gower. If she thought she could trick his son into marriage, and herself into the lady’s chair in the parlour which we had not been even allowed to enter, then she was mad with her vanity. She could tempt Jack – I was sure of it. But she would not be able to trick Robert Gower. I thought of the wife he had left behind him, crying in the road behind a vanishing cart, and I felt that prickle of fear down my spine.

‘Leave it be, Dandy,’ I begged her. ‘There’ll be many chances for you. Jack Gower is only the first of them.’

She smiled at her reflection, watching the dimples in her cheeks.

‘I know,’ she said smugly. Then she turned to look at me, and at once her expression changed. ‘Oh Merry! Little Merry! I didn’t mean to hurt you so!’ She made a little rush for the ewer and wetted the edge of my blanket and dabbed with the moist wool at my head and my cheek, making little apologetic noises of distress. ‘I’m a cow,’ she said remorsefully. ‘I’m sorry, Merry.’

‘S’all right,’ I said. I bore her ministrations patiently, but to be patted and stroked set my teeth on edge. ‘What’s that noise?’

‘It’s Robert in the yard,’ Dandy said and flew for the trapdoor down to the ladder. ‘He’s ready for church and Jack and Mrs Greaves and even William with him. Come on, Merry, he’s waiting.’

She clattered down the stairs into the yard and I swung open the little window. I had to stoop to lean out.

‘I’m not coming,’ I called down.

Robert stared up at me. ‘Why’s that?’ he asked. His voice was hard. His Warminster, landlord voice.

He squinted against the low winter sun.

‘You two been having a cat-fight?’ he asked Dandy, turning sharply on her.

She smiled at him, inviting him to share the jest. ‘Yes,’ she said. ‘But we’re all friends now.’

Without a change of expression, Robert struck her hard across the face, a blow that sent her reeling back. Mrs Greaves put out a hand to steady her on her feet, her face impassive.

‘Your faces – aye and your hands and your legs and your arms – are your fortunes, my girls,’ Robert said evenly, without raising his voice. ‘If you two fight you must do it without leaving a mark on each other. If I wanted to do a show tomorrow I could not use Merry in the ring. If you get a black bruise on your chin you’re no good for calling nor on the gate for a week. If you two can’t put my business first I can find girls who can. Quarrelsome sluts are two a penny. I can get them out of the workhouse any day.’

‘You can’t get bareback riders,’ Dandy said, her voice low.

Robert rounded on her. ‘Aye, so I’d keep your sister,’ he said meanly. ‘It’s you I don’t need. It’s you I never needed. You’re here on her ticket. So go back up and wipe her face and get her down here. You two little heathens are going to church, and mind Mrs Greaves and don’t shame me.’

He turned and strode out of the yard with Jack. He didn’t even look to see if we followed. Mrs Greaves waited till I tumbled down the stable stairs pulling on my cap and patting my cheek with the back of my hand before leading the way out of the yard. Dandy and I exchanged one subdued glance and followed her, side by side. William fell in behind us. I felt no malice towards Dandy for the fight. I felt no anger towards Robert for the blow he had fetched her. Dandy and I had been reared in a hard school, we were both used to knocks – far heavier and less deserved than that. What I did not like was Robert’s readiness to throw us off. I scowled at that as we turned out of the gate and walked to our right down the lane towards the village church.

There was a fair crowd beside the church gate and I was glad then that I had not kept my breeches. All the way up the path to the church door heads were turned and fingers pointed us out as the show girls. I saw why Robert had been so insistent that we behave like Quaker servant girls and dress like them too.

He was establishing his gentility inch by inch in his censorious little village. He was buying his way in with his charities, he was wringing respect out of them with his wealth. He dared not risk a whisper of notoriety about his household. Show girls we might be, but no one could ever accuse any of Robert Gower’s people of lowering the tone.

Dandy glanced around as we walked and even risked a tiny sideways smile at a group of lads waiting by the church door. But Robert Gower looked back and she quickly switched her gaze to her new boots and was forced to walk past them without even a swing of the hips.

I kept my eyes down. I did not need a glance of admiration from any man, least of all a callow youth. Besides, I had something on my mind. I did not like the Warminster Robert Gower as I had liked the man on the steps of the wagon. He was too clearly a hard man with a goal in sight and nothing, least of all two little gypsy girls, would turn him from it. He had felt that he did not belong in the parish workhouse. He had felt that he did not belong in a dirty cottage with a failed cartering business of his own. His first horse had been a starting point. The wagon and the Warminster house were later steps on the road to gentility. He wanted to be a master of his trade – even though his trade was a travelling show. He had felt, as I did, that his life should be wider, grander. And he had made – as I was starting to hope that I might make – that great step from poverty to affluence.

But he paid for it. In all the restrictions which this narrowminded village placed on him. So here his voice was harder, he had struck Dandy, and he had told us both that he was ready to throw us off.

I, too, wanted to step further. I understood his determination because I shared it. I wanted to take the two of us away. I wanted to step right away from the life of gilt and sweat. I wanted to sit in a pink south-facing parlour and take tea from a clean cup. I wanted to be Quality. I wanted Wide.

I watched him and Mrs Greaves closely and I kneeled when they kneeled and I stood when they stood. I turned the page of the prayer book when they did, though I could not read the words. I mouthed the prayers and I opened my mouth and bawled ‘la la la’ for the hymns. I followed them in every detail of behaviour so that Robert Gower could have no cause for complaint. For until I could get us safely away, Robert Gower was our raft on the sea of poverty. I would cling to him as if I adored him, until it was safe to leave him, until I had somewhere to take Dandy. Until I could see my way clear to a home for the two of us.

When we were bidden to pray I sank to my knees in the pew like some ranting Methody and buried my face in my calloused hands. While the preacher spoke of sin and contrition I had only one prayer, a passionate plea to a God I did not even believe in.

‘Get me Wide,’ I said. I whispered it over and over. ‘Get me and Dandy safe to Wide.’

6

We kept the Sabbath, now that we were on show as Robert Gower’s young ladies. Dandy and I were allowed to walk arm in arm slowly down the main street of the village and slowly back again. I – who could face dancing bareback in front of hundreds of people – would rather have walked through fire than join Dandy in her promenade. But she begged me; she loved to see and be seen, even with such a poor audience as the lads of Warminster. Also, Robert Gower gave me a level look over the top of his pipe stem, and told me he would be obliged if I stayed at Dandy’s side.

I flushed scarlet at that. Dandy’s coquetry had been a joke among the four of us in the travelling wagon. But in Warminster there was nothing funny about behaviour which could lower the Gowers in the eyes of their neighbours.

‘It’s hardly likely I’d fancy any of those peasants!’ Dandy said, tossing her head airily.

‘Well, you remember it,’ Robert said. ‘Because if I hear so much as a whisper about you, Miss Dandy, there will be no training, and no short skirt, and no travelling with the show next season. No new wagon of your own, either!’

‘A new wagon?’ Dandy repeated, seizing on the most material point.

Robert Gower smiled at her suddenly sweet face.

‘Aye,’ he said. ‘I have it in mind for you and Merry to have a little wagon of your own. You’ll need to change clothes twice during the show and it’ll be easier for you to keep your costumes tidy. You’ll maybe have a new poorhouse wench in with you as well.’

Dandy made a face at that.

‘Which horse will pull the new wagon?’ I asked.

Robert nodded. ‘Always horses for you, isn’t it, Merry? I’ll be buying a new work horse. You can come with me to help me choose it. At Salisbury horse fair the day after tomorrow.’

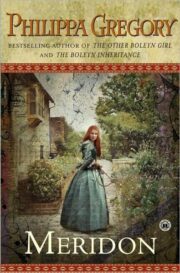

"Meridon" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Meridon". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Meridon" друзьям в соцсетях.