Bulgakov placed his face down on the desk, his forehead against the page. As if he could take the words directly from his cranium and impart them there. As if he could be spared the need to think any of it through.

They were on a different bench than before. Ilya laid his raincoat over the back of it to dry. Each seemed lost in thought. She could provide no reason for why they’d stayed. Perhaps he was still concerned about her; the juice had helped. Soon his clothes would be dry. Soon they would leave, each in their own direction; they would part ways forever and she’d carry her knowledge of him with her.

“Why writers?” he asked her.

At first she was uncertain of what he was asking; then she understood this was about her romantic involvements. She wanted to say there was no particular reason. She stared at the water.

She wanted to correct him by saying Bulgakov hadn’t been a romantic involvement.

Perhaps his question was a caution. She was reminded of the danger she’d felt before; the sensation was now a memory. She no longer felt any particular threat. She looked at his hand where it rested on his thigh. It was large and angular. It seemed itself a self-aware organ. She could envision it nesting a fledging bird; in her imagining his fingers curved around it, protectively. The bird’s eyes in its downy face were black beads. It looked about, uncertain, yet not altogether protesting. Then, as though without reflection on their intent, the fingers closed in and broke the creature’s neck.

He moved his hand to the bench between them and she jumped a little. He didn’t appear to notice.

This was a man who represented everything she detested. Yet here they sat together. The sun showed no preference toward one over the other. The universe itself seemed ambivalent of them: one might survive, one might not; it was all the same. She’d not given thought to the concept of God in many years, yet He seemed at that moment to be utterly remote—not even a pinprick in the sky. It was easy to believe that He didn’t have a preference either.

This was a man who was everything she detested. She didn’t know the specifics of his involvement in the arrests of Mandelstam or Lev Gumilev—or others—but she could assume the worst. Yet she remained; she shared this bench with him. This planking, this park, this sun, this sky. Was he only an emptiness that was capable of intolerable deeds? What was missing in her that she didn’t immediately leave?

Perhaps God was there, only silent. Silent and curious.

Ilya seemed to be waiting. She was about to answer as she’d first thought: there was no particular reason. But he spoke again.

“It makes it harder for the rest of us, you know.”

His question hadn’t been a caution.

His hand remained, resting against the plank. She watched it as one might a wild animal; something not inherently dangerous or with malice, but nevertheless unpredictable. She could be drawn to it, she thought, and she was surprised by this. Perhaps it gave some license for her own wildness.

Would she risk the touch of his hand on her neck just to feel it there?

It would be the heat and lack of food that turned her thoughts so strangely. When she looked down again, his hand was in his pocket and she was given over to the sense of something being forgotten or mislaid. Or something imagined; yet wholly unobtainable, just the same.

She expected never to see him again after that afternoon.

PART II

NEVER TALK TO STRANGERS

CHAPTER 10

In the early years, the artists and intelligentsia were eager to remake the world in their leaders’ vision. It was the dawn of a new century; the climax of a millennium. They weren’t just Bolsheviks; they were Modernists, Futurists, Constructionists. The Ivan Ilychs of their past with their caged canaries and dusty rubber plants were to be plowed under in the building of a steel-girded utopia. The writer and poet Vladimir Mayakovsky believed the Revolution had quickened their future. His play, Mystery Bouffe, produced in 1918, dramatized the conquest of the clean and proper bourgeois by the grimy, stubble-faced proletariat. At its climax, the audience joined the cast onstage and with them destroyed the theatre curtain that had been painted with symbols of the old world. Spoke Diaghilev in 1905, “We are witnesses of the greatest moment of summing up in history, in the name of a new and unknown culture, which will be created by us, and which will also sweep us away. That is why, with fear or misgiving, I raise my glass to the ruined walls of the beautiful palaces, as well as to the new commandments of a new aesthetic.”

In early spring of 1930 Mayakovsky was found in his apartment with a gunshot wound to his head. His death was labeled a suicide. In the previous year, he’d published a dazzling satire on Soviet behavior and bureaucracy, and was immediately damned by the authorities. His detractors concluded he’d be neither relevant nor even circulated in twenty years’ time.

In his apartment that morning, the agent in attendance pressed the revolver’s barrel against the writer’s temple, then angled it slightly back, toward the opposite ear, to assure the kill. The writer’s eyes bulged forward; his pupils darted repeatedly as if he needed to see the thing. He no longer made sense. Most pleaded until the end. This one instead over and over repeated, until there was only a mutter of words:

What did it matter?

The agent disliked poets in particular. Pick something, he told him. He thumped the table; it was strewn with handwritten pages.

The writer looked down, then seemed to understand. His suicide note.

What did it matter? The words softened to a chant. His hand touched a page, then moved to another, as if trying to recall something forgotten. He picked up his pen and added a line. He held it for a moment longer as he read over the words.

Mayakovsky looked at the agent and mouthed the question one final time. Only the question had changed. There was the smell of gunpowder and burnt skin. Eyes turned skyward. He fell from the gun’s barrel as if indeed it’d been holding him up all along.

The poet’s final question had been genuine. It was the one they all asked.

When did he stop loving me?

Stalin kept the poet’s original note in the side drawer of his personal desk until his death in 1953.

Years later it was revealed that the apartment where Mayakovsky had been found had had a secret entrance within a closet. His lover Lily Brik had been an informant for Stalin’s political police. The poet’s death tolled throughout literary Russia with an unmistakable voice: there was no place in Soviet literature for the individualist. The land that had borne Pushkin and Gogol, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, Chekhov and Pasternak, fell silent.

It was Bulgakov’s third banquet in as many months; these were Party affairs and though he was not a Party member it would be ill-conceived to decline the invitation. He had drunk too much at the last one and his suit jacket had disappeared from the back of his chair. He cursed himself for this; it’d been his second best, so when the invitation for the next banquet came on its heels and his other jacket was still with the laundry woman, he was left with his third, which, upon inspection, could hardly be called a jacket but perhaps the ghost of one, the fabric along its back seam so threadbare as to rip with the slightest pressure. He decided to wear his overcoat instead. The room would be dark, he determined, and once the liquor was flowing no one would notice or care.

This one was in honor of the novelist Poprikhen. Some newly-hatched award for his most recent effort. Bulgakov had written a letter to the editor of Crocodile in praise of it. He’d written many such letters, opining on the works of his various contemporaries and was surprised at the ease with which they made their way into print. He was also surprised by his colleagues’ reactions. At the Writers’ Union, he had become someone to know. Introductions and invitations flew about—“Gregor, Gregor! You must meet Mikhail Bulgakov—Come! Oh wait, you’ve missed him, but here he comes again from the bar, and this time you will have your chance.” “Bulgakov—my man, next summer when we open up the dacha you will join us—now don’t shake your head! Irini—my dear, didn’t he promise? See—you’ve promised; my wife has the memory of an elephant. We have the best chef in the district—you will be as fat as a bathtub when you return—I promise you!”

Despite his frequent attendance at the Writers’ Union, he never saw her there. From time to time he would scan the room, registering each figure anew as though it was possible his memory might misrepresent her. He wondered if she was avoiding him. He could have gone to her apartment and he reasoned that he’d been busy with the novel and the play, yet in truth, he was anxious of her response. He could imagine her under his arm; he looked about at the women near him who wished they occupied that spot, and he remembered her face from the vestibule of Mandelstam’s apartment. Her careful apportionment of hope and distrust. Would it now be entirely distrust? When it was determined that his play would be reinstated at the MAT, he sent her tickets to its opening. It was months away, but he liked to imagine her there in the seat he’d chosen, her face illuminated by the lights of the stage. He could wish she might come alone, but he doubted it, and had sent her a pair of them as a way of demonstrating this kind of understanding. He didn’t allow himself the hope of her coming to find him backstage afterward, pressing her hand upon his arm, revealing in her eyes the wonder at what genius he’d achieved. He imagined theirs was a different kind of communion. It existed on a higher dimension.

He would then berate himself for these dreams; how pathetic they were! This was no way to live. He looked around at the swell of conversation and laughter—this was not how others lived. Already someone had drawn their arm around him—he joined their conversation, laughing as they did, at the expense of something he knew not what.

He arrived at Poprikhen’s banquet late; the room at the Dynamo Club was already filled with people; tables were set in expectation of multiple courses; silver and glassware glittered under low chandeliers—yet, to Bulgakov’s dismay, not even a single hors d’oeuvre had been passed. It all seemed a sad trick of luring together a room of hungry writers. Poprikhen appeared at his elbow; quickly he led him to a seat marked with a name card; it was next to his—the guest of honor. Poprikhen touched his breast pocket. Bulgakov wondered if he was yet beefier than before and if this could be possible without him actually exploding.

“It was my request,” said Poprikhen, his hand to the back of Bulgakov’s chair. “I know we’ve had differences in the past, but I credit you—” It seemed he might mint a tear from between his thick lids. “You, my friend.” He would not try to finish. “Thank you!” he added huskily.

Bulgakov mimicked the other man, waving his hand in the general vicinity of his breast pocket. His fingers brushed the coarse fabric of the overcoat and he quickly stopped, not wanting to call attention to its oddity; nor did he want to prolong any false gesture of affection. He scanned the table; it wanted for no treasure other than food. Poprikhen seemed to anticipate his question.

“We’re waiting,” he said. “It is rumored he might attend.” He could not suppress the joy from his words.

At that moment the heavy double doors of the club were opened. Half a dozen men firmly but politely pushed aside those standing near; on their heels several committee members entered. There was a whoop from the crowd, then loud applause. Bulgakov struggled to see—there between milling bodies; it was Stalin himself. Oh dear god, he thought.

Every exit was maintained by some semblance of guards or police. He could make an excuse that he was ill. They’d not deny him departure with that pretext. Poprikhen’s hand closed around his forearm. His face was even redder than before; bursting with emotion he was nearly apoplectic. “This will be remembered as the greatest day of my life,” he sputtered. Tears ran down his cheeks. The central committee members made their way to the head table. The room had quieted; only happy expectant twitterings could be heard. Bulgakov edged backward slightly, hoping to be lost in the novelist’s tremendous silhouette. Everyone waited for Stalin to take his seat. No one moved.

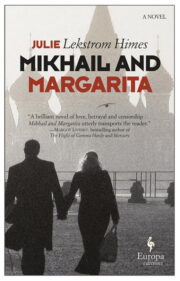

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.