“Bulgakov—man, is that you?” Stalin’s voice thundered down the table. There was a horrible pause; everyone in the room waited—Bulgakov leaned forward and looked to where Stalin stood.

“So what is it, then—are you coming or going?” said Stalin.

Bulgakov could not imagine what he meant. “I beg your pardon,” he said.

“Your coat—take it off! Join us for this sumptuous meal!”

Oh dear god, he thought again. He started to remove it, then stopped. “I’m sorry—my suit jacket—I haven’t one.” He stammered, embarrassed and frightened. The room as well seemed to inflate with these same emotions, faces up and down the table, as though his confession spoke poorly for all there, all of them waiting for Stalin’s reaction.

“What! No suit jacket!” Stalin’s roar seemed laced with amusement.

“It was stolen, I’m afraid.”

“My writer without a jacket—that cannot be! Ordzhonikidze, give him yours then,” said Stalin to the man on his left.

“What?” said the Commissar.

“We can’t have our favorite writer without a suit jacket!” Stalin rubbed his hands together as though in pleasure of having solved the meddlesome problem. Bulgakov could only think of Mandelstam’s words—ten thick worms were his fingers. When Ordzhonikidze didn’t immediately disrobe, Stalin stopped rubbing and glared at him. Did the Commissar of Soviet Heavy Industry value a suit jacket more richly than his leader’s pleasure? Ordzhonikidze looked terrified—the entire room reflected their terror for him. He handed his jacket to a waiter who flew like the devil to Bulgakov’s chair. Bulgakov put it on. It hung poorly, but Stalin appeared satisfied. He took his seat, and immediately, food and drink seemed to appear from nowhere.

Toasts were given. Stalin was first, saluting poor Poprikhen; however, he gave the wrong patronym and his error was perpetuated in all other toasts of the evening. Bulgakov sensed Poprikhen’s efforts to not let this blemish the event. At one point he leaned heavily against Bulgakov’s shoulder. “I may not be his favorite writer,” he said, drunkenly. “But I have my seat next to his.” With every toast his tears had flowed and now his face was spotted with their tracks. As soon as they were finished and the Party leaders left, Bulgakov got up to find other company. The music had begun. Poprikhen was singing with a few others, crying again, and appeared not to notice.

Bulgakov wanted a fresh drink and while it had seemed the waiters were as populous as the guests, now that he required one, they were not to be found. He felt somewhat abandoned and for a moment, despite the crowded room, his orbit was a lonely one. Being Stalin’s favorite writer appeared not to ensure one’s popularity. Indeed, he sensed a vague inquisitiveness in those near him, and in equal measure, their desire to maintain a certain distance. He noticed a woman’s stare; their eyes met then parted and she turned back to her conversation laughing suddenly, as though she’d never left it. Others in her small group laughed too. They were wondering what he’d done to claim that title, he thought. Though they would not offer it aloud, they were each in secret giving harbor to their own suspicions. Another, the man at her side, glanced at Bulgakov’s suit jacket—or rather Ordzhonikidze’s, then blankly looked elsewhere as though like Bulgakov he was in fact in search of a waiter. He shook his glass slightly as a kind of testament to this. He leaned into the woman’s ear as he spoke briefly. To his query, she shook her head.

Bulgakov imagined wedging himself between them. Perhaps this Bulgakov is an old family friend, he’d offer. Perhaps he’d shown some valor in battle. Or medical care for some unsavory condition and, of course, all confidences would be maintained. Such favoritism wasn’t necessarily the result of intrigue or cowardice. Such affection was not obviously the reward of a betrayal.

“Have you been to these parties before?” At his side was the drunkard from the restaurant some months ago. Ilya Ivanovich reintroduced himself. “I remember,” said Bulgakov. There was no hint of drunkenness; he looked in fact as though he’d not taken a drink since. A waiter appeared. Ilya repeated his question.

“This is my first,” said Bulgakov. He spoke to the waiter as though he’d asked. He couldn’t explain why he lied so easily over the trivial fact. Anything to extract himself from a prolonged conversation, though why such should be avoided, he likewise couldn’t explain.

“If this is your first, then you should have some fun with it,” said Ilya. “Order anything—the most exotic thing you can imagine. They will produce it.”

Bulgakov was surprised by his suggestion. “Persian Vodka,” Ilya said to the waiter, deciding then for the both of them. “Bring the bottle, so we can see it.” Bulgakov would not have guessed that Persians manufactured vodka. The waiter registered the request with a slightly glazed expression, as though imagining the trek he was to undertake. This could take a while.

“I understand the MAT will produce your play,” said Ilya. “My congratulations.” He touched the breast pocket of his jacket over his heart. His gesture was similar to Poprikhen’s, only Ilya seemed more to be searching for his.

“So they say,” said Bulgakov with brisk cheerfulness.

“Tell me again, its name? I’d like to see it.”

“Oh, I shouldn’t think so,” said Bulgakov quickly.

“Why not?”

“A Cabal of Hypocrites.”

“You must be delighted,” said Ilya. “Many will want to see it.”

His words reminded Bulgakov of their other conversation. The memory of his earlier anxiety returned. “Would you like to meet the guest of honor?” Bulgakov hoped to pass him along to someone else. He nodded toward Poprikhen.

Ilya leaned in to speak though this was unnecessary. There was no one nearby who might hear them. His breath was unpleasant on his cheek. “I believe I’m speaking with him now,” he said.

Bulgakov was sufficiently vain to have at one point desired such admiration. Suddenly he wished he might disappear.

“I apologize,” said Bulgakov. “Why I should fail to remember is rather embarrassing—what is your interest in literature?”

“I suppose I am a critic of sorts.” Ilya smiled.

“Still,” said Bulgakov, his unease growing. “I feel I should ask for your papers.”

“Then you should be disappointed. I carry none.”

His anxiety was transformed into something more certain. Yet why was this Ilya Ivanovich interested in him? He wasn’t political. He wasn’t another Mandelstam. What had he done to attract such attention? He sensed a kind of chase and felt the need to escape, to hide, more strongly than ever.

“I wonder,” said Ilya. “How does one become the General Secretary’s favorite writer?”

“I imagine one would have to be a good writer,” said Bulgakov without much conviction.

Ilya seemed amused. “There are a lot of good writers,” he said. “But why not—let’s say that might have something to do with it.” There was a savageness in the way he put this last part.

The vodka arrived and was poured into two glasses. Alborz vodka, it was indeed Persian; the waiter looked only slightly fatigued. Ilya raised his to give the toast. Bulgakov remembered this same gesture from before and he felt a sudden and sharp longing for Margarita as though he’d just overheard the mention of her name.

Ilya paused. “I’m sorry,” he said, his glass hanging in midair. “I’m at a loss.”

“To better writing,” said Bulgakov. He surprised himself a little with this.

Ilya’s lips curled slightly. He then drank.

“This stuff is wretched, isn’t it?” Ilya set his glass on a nearby table as he turned to leave. His words were an indictment—not of the vodka, but of the gathering itself, its pretense of opulence; perhaps it was a condemnation of their times.

Bulgakov watched him disappear into the crowd. Strangely, he felt less endangered, as though the drink had been an antidote. Was he not wearing Ordzhonikidze’s jacket? Ilya had wondered why he was Stalin’s favorite writer. Because I’m a damn good writer, he thought with a fierceness that matched Ilya’s.

On the other side of the banquet hall, Poprikhen had been dancing, but was now splayed across several chairs. Another dancer fanned a napkin over his face ineffectually. Bulgakov suspected he was the only one in attendance with any medical training. Poprikhen greeted him with a drunken sputter. Bulgakov found a pulse in the man’s meaty wrist and told him to rest for a while.

“Will he be all right?” A woman’s voice came from behind.

Bulgakov turned. It was Margarita.

How did she look? Not more aged; nor more youthful. She’d neither gained nor lost weight. There was a change, but not in her appearance—perhaps it was the distance she maintained. As well there was a set to her features. A calculation to what she might reveal. He couldn’t blame her for this. She kept herself at a difficult reach so he simply held his hands out to her, palms upward as if he was checking for rain, and asked how she was.

She didn’t answer his question.

“Congratulations on your play.” Her smile was warm and genuine. “I’d heard—then I received your tickets. It was very generous. I’m not sure why you sent them but thank you.”

He was vaguely aware of the room around them, the shifts of light, of bodies. Couples were dancing. She alone seemed fixed.

“I didn’t expect to see you tonight,” he said. “You look—wonderful.” He wondered who she was with.

A dancer nearly careened into her; Bulgakov lifted his arm to shield her.

“We should either dance or leave,” he said. She shook her head beautifully.

Instead, she told him Mandelstam had been released. He and his wife were to be relocated to Cherdyn. There would be an opportunity to see him if he liked, to say good-bye; tomorrow, just after noon. If he liked, she repeated. She seemed to step around this possibility with caution. He wondered if she’d heard Stalin’s pronouncement. He could not imagine what she thought of it.

“Yes, of course,” he said quickly. He’d not anticipated having to face Mandelstam again; at least not this soon. He wondered how she’d come to hear of his release. “This is amazing news,” he added, trying to fuel his words with some enthusiasm. “Thank you for thinking of me,” he said.

“It was Nadya’s idea,” she said.

“But you took the trouble.”

Still, it was Nadya. She would take no credit.

He wondered if she was seeing someone else and this depressed him.

They agreed to meet near her apartment. He thought to suggest his place instead, but didn’t. He didn’t want her to refuse again something he might offer, as though this could form a habit that would be difficult to overcome.

She hesitated. “You were speaking with someone,” she said. Her manner had changed; she seemed uncertain, almost shy.

“You remember,” he said. “The man from the restaurant. The drunk—the sturgeon.” He hesitated in giving Ilya’s name, as though this would summon his form. He repeated instead. “The drunk.”

She nodded. “I noticed you were talking.” She seemed to want to say more, but looked uncomfortable, possibly even worried for him.

Was her discomfort wrapped up in her memories of that night, with their later encounter that she longed to set aside? Or had she observed something from across the room; something vague yet troubling. Perhaps it was her concern that gave him more courage.

“We talked of the play,” he said.

“We thought we’d never see him again,” she said. He decided she seemed more shy than worried.

“Do you remember that terrible wine?”

“The entire evening was strange.”

Not disagreeable, though. Not regrettable, only strange. He wished he could go back to it; he wished that he would have stayed and not left her that morning. There would have been no trip to the Kremlin. He imagined finding their way under her blankets, feeling the warmth of her shift against him as she moved. The world would have stopped there.

He thought to reach for her but she stepped back as though she’d sensed it. Time had indeed moved onward. Yet she could not be heartless. She placed her hand on his jacket sleeve.

“It is exciting—your play,” she said. Her eyes were shining. He didn’t try to understand her misgivings any further. He wondered what else he could do to make her happy. What more he could promise her?

“It will be good to see Osip,” he said. He hoped his eagerness would sound credible.

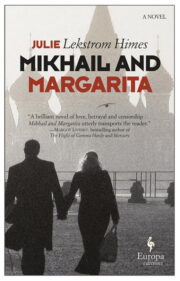

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.