“Do you think so?” she said. “I expect he will be quite changed. Physically, I mean, of course. I’m a bit nervous.”

Briefly he imagined not appearing at the appointed time. He imagined Margarita waiting, scanning the streets for him before going on alone. For some reason, an arbitrary universe had afforded him a second chance. Perhaps it was not so arbitrary.

CHAPTER 11

They met just before midday and walked to Patriarch’s Ponds together. Her step was slightly ahead of his. As they crossed the street, her arm shot into the air. A figure rose from a small table set among others near an open kiosk, an overhang of aged trees shading it; beside him, a second figure, a woman, remained seated.

Mandelstam was barely recognizable.

Bulgakov was suddenly flooded with guilt; his recollection of the Writers’ Union, the apartment vestibule, his meeting with Stalin; as if these actions were responsible for the transformation before him. He slowed. She moved ahead and they walked the last few paces obliquely.

The once dark fringe of hair was grey and shaved close. His rotund form had withered; he’d become a whisket of limbs and torso such that he appeared taller than before. She lifted her arms in an expectant embrace. Bulgakov marveled at her fearlessness of this specter.

Mandelstam raised an arm; a bony thing emerging from what seemed to be the cavernous opening in his short-sleeved shirt. The other leaned heavily on a cane. As she hugged him, he leaned forward, to steady himself against her. Bulgakov and Nadya watched this, yet made no move to acknowledge each other. Bulgakov then clasped him about the shoulders; the circle of his arms that closed in around the poet was pitifully small.

“This is wonderful,” said Bulgakov, trying to manufacture enthusiasm.

Mandelstam turned to his wife, proposing that she and Bulgakov might enjoy a short walk, with a smile that suggested the plan had been previously discussed and at least tacitly agreed upon. Bulgakov offered his arm to her. Margarita was already seated; she held the poet’s hands, or rather, maintained hers like small tents pitched over his that rested loosely on the table. Nadya pointed out the pond where two swans passed serenely. They followed the walk that circled the water.

“I saw Tatiana last week,” she said. “She asked after you. She looks good.” She didn’t say what she’d told his ex-wife. “She cut her hair. It’s quite stylish.”

“She’s a pretty girl,” he said.

“She said something about some dishes of hers.”

He knew the ones of which she spoke. A wedding gift from friends of hers. They’d had a special place. She’d left them behind and because of them, for a time, he was certain she’d return. “I don’t know,” he said slowly. He couldn’t recall when he’d last seen them. It was possible they’d been broken in the search.

Nadya seemed to assume something else had happened. “She said it didn’t really matter. I said I would ask, but she said not to bother. She said they weren’t particularly important to her.” This last bit seemed more of a pronouncement. As though nothing from his wife’s time with him could have held any lasting importance.

He’d never thought of the two women as friends. Both had married writers. Both had been hurt by them, though in different ways. Yet it seemed one was willing to wound for the other, on the other’s behalf.

“I told her,” she went on. “I said, ‘How does one lose dishes? He must still have them somewhere.’ ‘Oh, you know Bulgakov,’ she said. ‘He’d have used them for an ashtray if I’d let him. Or to wedge under a table leg. You know Bulgakov.’” Nadya laughed at this. It wasn’t clear if the laughter was recreated for him, like the conversation, or simply her own.

“I know the ones,” he said. “She’d want them.” He felt self-conscious in correcting her, in defending his relevance in his ex-wife’s memory.

One of the swans lifted up from the water briefly; its tremendous wingspan extended over its mate; the sound of its wings against the air was like distant thunder; others walking nearby turned. Nadya studied the fowl as though it carried a message that was particular to her.

“She said it wasn’t important.” This time the bite was gone. She sounded only tired. They were dishes after all; not lives broken and swept aside. The swan settled again.

“We leave tonight,” she went on. “We can bring our clothes. No books.” A list of suggested items had been provided. Like a children’s camp, she mused.

“I’ve heard Cherdyn can be pleasant in the summer,” he said.

They were over halfway around the pond. She removed her arm from his and crossed them over her chest.

“I’m not entirely sorry to be leaving this place,” she said. He could see she was watching Osip and Margarita on the other side. “I won’t miss this.”

“Will he be able to write?” he asked.

She didn’t know. He hadn’t slept since his release.

That wasn’t what he’d meant but he let it alone.

“Has he talked about what they did to him?”

She said nothing for a moment, only hugged her arms around her torso. “No—perhaps we can hope that he will forget. We should hope for something.” As though it was the act of hoping—not the thing itself, not the granting of it—which made it possible to continue.

He sensed her manner change with this. Impart a new sympathy. But perhaps in larger dimension there was a growing acknowledgment of endings. Their walk would soon be through. The time of bitterness and reproach was over. It was a time for amends. She took his arm again.

“I remember when he first brought you to our apartment. You couldn’t have been in Moscow very long. Do you remember? You were so reserved. And shy. Every time I stood, you leapt to your feet as well and Osip laughed at you. I thought—here is this physician. What must he think of our bohemian life? Emptying our pockets to their very lint just to gather enough to buy a couple of eggs or a bottle to share. Who would want this, I thought? Why would he want this? Osip said—I think he can write—and I thought, ‘So what. Why would he want to?’”

“You were kind to befriend me,” he said.

Nadya smiled a little. “That was Osip,” she said.

“No, that was you as well, Nadyusha.” She didn’t argue with him.

“His poems aren’t lost, you know,” she said. She touched a finger against her temple. “I memorized them all. You needn’t have worried.”

With this, they both looked toward Mandelstam and Margarita.

Margarita sat erect, her hands in her lap. Mandelstam drew his hands along the sides of his scalp; it seemed he’d forgotten how little remained there. Bulgakov recognized this gesture. He wondered what she’d asked that he could not fulfill.

“Osip is lucky to have you,” he told her. He said this absently, still thinking about Margarita. Nadya seemed grateful and he smiled to reinforce his words. He thought them both supremely unlucky. He thought it was possible that she was the least lucky of all.

Both Margarita and Mandelstam looked up at their approach as though their time allotted had been overestimated. Margarita had been crying. She got up and moved away from the table. She stared at the water. She seemed not to notice the swans.

Mandelstam nodded to his wife; again this appeared to be expected and Nadya went to sit on a bench a short distance away. She took a cigarette from her purse and lit it. Bulgakov took off his suit jacket and sat in the seat Margarita had vacated. It was warm; he pushed up his sleeves. Mandelstam watched his wife for a moment.

“You look well,” said Bulgakov. “All things considered.” He stopped, feeling clumsy.

Mandelstam turned back; he appeared not to have heard him. “Do you remember when we first met?” he said.

Bulgakov remembered. It had been after a coffeehouse reading, one of Bulgakov’s first, not long after he’d moved to Moscow. There’d been many amateur writers that night, reading from their work. He remembered the soft flesh of the poet’s handshake. Somehow it’d made him less fearful of him, his ability to crush all hope, until the other man smiled, his lips parting to speak, then all fear rushed back.

“Do you remember what I said to you?”

Mandelstam had said that someday he would come back to this same coffeehouse to listen to this same man, only the line would go around the building, perhaps even the block, for they would stand for hours, happily, to hear the voice of a great writer. Of course Bulgakov remembered. He’d gone home that night and written it down.

“You were very generous to me,” said Bulgakov.

“Was I? I couldn’t remember. Did it matter?”

“Of course.” A small twinge of that fear returned.

“If I had told you to go back to medicine, would you have?”

Mandelstam patted the front pockets of his shirt. He removed a silver case, opened it, and placed its last remaining cigarette between his lips. Bulgakov lit it for him.

“It’s too late for that,” said Bulgakov. “Your words did their damage.”

The poet sat back. He worked the cigarette between his lips, then removed it.

Between them lay a green worm, a moth larva. It had fallen from an overhanging branch to the table’s surface. Some unlucky turn of a leaf, a wisp of breeze, and a misstep had sent it from its universe of green. Neither of them spoke; it was something to brush aside. For a moment, its legs moved helplessly; then it curled inward to right itself. Immediately two black ants set upon it as if waiting for that opportunity. In their arms, the larva contracted reflexively, then ceased to struggle, paralyzed from their bites of formic acid. The ants hesitated at the table’s edge, burdened with their prize, then disappeared over the rim. Mandelstam maintained his gaze on that spot. His frown deepened.

The larva would not know a life of wings and air; it would not grieve that loss. To this larva, the meaning of its life was to provide food for ants.

“I’ve done things—will you take an old man’s confession?” Mandelstam looked away again. “God—it’s beautiful today.” Despite his words, his expression was of one who mistrusted what he saw.

“You have nothing to confess,” said Bulgakov. He tried to sound assured of this.

“I’d always considered the possibility of arrest,” said Mandelstam. “I had believed it was only a matter of time.” He inhaled from his cigarette. His hand visibly trembled and he lowered it quickly.

“I’m not sure what you want to hear. The physical details aren’t important, I suppose. At first you live for your release. That is the composition of your hours. When you will see the sky again—the trees, the sun. Your wife. You live for things you never gave thought to. You believe if you can be strong, you can withstand them. You believe such strength is possible.”

“You are strong,” murmured Bulgakov. “The strongest man I know.” This part he felt truly.

Mandelstam lowered his voice; he seemed anxious to continue. “I don’t know if it’s the beatings. Or the isolation. Maybe something else. At some point you stop living for your release. You stop thinking of your wife, of your future. You stop thinking.” He paused. “You only live. Questions are asked and you answer them. There is food and you eat. There is pain and you cry openly. If your life were to suddenly end; you think this is how life is; this is how it ends.” He seemed to search Bulgakov’s face for comprehension. “You have no regret, no sense of loss. No care for those you leave behind. You do not consider that it could have happened another way.”

The loveliness of the afternoon grew deceptive. “Those are terrible circumstances,” said Bulgakov.

Mandelstam sat back a little. A piece of ash fell from his cigarette. He flattened it against the table with his thumb. “Questions were asked and I answered them.” He looked out over the pond. “Many questions. About a lot of people.” It seemed he was counting their number among those enjoying the afternoon as though it was this reckoning for which he was accountable.

“Who did they ask about?” said Bulgakov. His apprehension grew. What could they want to know?

“Among other things—the names of those who’d heard the poem.”

His poem—as though it was a contagion. For some diseases, the afflicted couldn’t be saved.

Mandelstam’s face remained impassive, unapologetic. Harsh experience had stripped all comfort. Truth would no longer be urged gently forward, to steal upon one as in the verse of a song. Truth would be delivered bare-boned. He had no desire for Bulgakov’s sympathy. He would dare Bulgakov to look away from his actions, to layer himself in kindness and pity and self-deception; he himself could do it no longer as though he lacked the appendages for it.

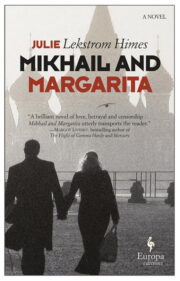

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.