Bulgakov posted letters to Stalin nearly every day. There was never any indication that they were read. He went to Lubyanka looking for Ilya but was turned away. He stood in long queues with the families of other prisoners. He thought they all looked the same—pale, shell-shocked. They spoke not at all to each other, as though this would acknowledge some terrible commonality. As though it would unduly test their faith that their particular case—their husband, their wife, their child—was different from the rest. They waited for the opportunity to plead with a guard whose lips were hidden behind a small metal slit in a wall. Ten-second conversations that were unvaried. The guard would review several lists for the given name. A rattle of paper might be heard but not always. Sometimes there was the odor of onions and animal fat.

Bulgakov wished he could talk to Nadya. He wondered how she had managed those weeks waiting for some bit of information, yet dreading it too. What would she have thought of this turn of events? Once again, her husband and his lover were aligned in ways that excluded her. Would she feel vindicated or would this be a different kind of loss? Or had all feelings been wrung dry?

“Margarita Nikoveyena Sergeyev.” The sound of it fled quickly and made for Bulgakov a renewed loneliness.

The voice paused. “I have no information available.”

How was that possible? “Every week I hear the same thing—do you know if she is even in there?” said Bulgakov.

There was another pause, and for a moment Bulgakov wondered whether if by deviating from the typical dialogue, he’d actually broken some internal mechanism. The voice returned.

“Is she out there with you?” it said.

“Of course not.”

“Then she is here.”

A woman behind him pressed against his coat. “You’ve had your turn,” she said. “Give it to another.” Bulgakov didn’t move.

“And if you were to have new information, what might that be?” said Bulgakov.

Another pause, then Bulgakov sensed a kind of sympathy to the words. “That she is no longer here, either.”

Bulgakov stood at the tram stop outside of Lubyanka, watching those who converged upon that spot waiting for their own particular route. He wasn’t certain whom he was looking for. There were office workers—men and women, older women, perhaps mothers in their own right, and younger, attractive ones. There were guards in uniform. Many read newspapers. Some smoked and kept watch down the avenue. Some stared into space. Several trams stopped and filled with passengers. Bulgakov continued to wait. The afternoon shadows began to lengthen. A women with a perambulator appeared. The baby was crying and the woman bobbed the handles, cooing into its cover, trying to soothe it. A youngish guard standing nearby glanced toward the child. Bulgakov could guess that from his angle he had some view of the carriage’s interior. Bulgakov surmised he was of lower rank given the few stripes across his sleeve. Perhaps the guard was only bored. Perhaps he was reminded of some younger brother or sister, some past time. He smiled slightly, and then, and Bulgakov’s heart rose with this, the guard’s expression shifted. There was a moment of understanding—the day was chilled, the wind stung, the afternoon had been long already and one could simply be hungry. Or bored and with only a child’s sensibility there would be no anticipation of what would certainly be relief once Mother could get it home. Yet unlike others nearby who either ignored or were irritated by the noise, unlike even the Mother who seemed to think jostling the buggy might provide some comfort, the guard seemed to understand the world of these things; he seemed to feel them all at once. It was there—one instant that said, Yes. I can imagine what you are feeling right now.

The tram arrived and the guard climbed in. Bulgakov followed.

His interview with Pravda, rescheduled now for the third time, was that evening. The tram was headed in a different direction.

CHAPTER 24

A clock hung on the wall inside her cell. For sixteen minutes each day, sunlight passed through a single, high window and painted a rhombus of light on the cement floor. For those sixteen minutes, she sat in the light, feeling the coolness seep through the fabric of her skirt. For those minutes the rest of the cell seemed darker.

Each day she followed the guards down two flights of stairs to a room that was painted white on the top and blue-grey on the bottom. Here her interrogators waited. There were three of them. She did not know their names. She called them Matthew, Mark and John. Matthew was handsome and in some ways her favorite. He wasn’t interested in learning of her anti-Bolshevik sentiments, if indeed she had any. He had imagination.

Their first session, he held her hand at the beginning as if they’d been formally introduced. He seemed to linger over it, admiring its structure, and for a moment she was self-conscious of his attention. He then let go.

“Take off your underwear,” he told her.

“What? No!”

There was an explosion of light, then pain. She fell to her hands and knees. No one in the room said anything or moved to help her. She touched the inside of her cheek with her tongue where it’d been torn by her own teeth. She got up, for a moment unsteady, then lifted her skirt, slid her underwear down to her ankles, and stepped out of them. She held them in her hands, her arms crossed over her torso. Tears came and rolled down her cheeks. Matthew nodded to one of the men behind her and her arms were lifted and extended over her head. Loops of rope were tied around her wrists and then to a hook that hung from the ceiling. The hook was raised until she was standing on her toes.

“Oh! Oh! Please! I can’t—please!” Her voice sounded muffled, her arms pressed against her ears. She wanted to cross her legs but couldn’t maintain her footing. Matthew didn’t respond. He walked around her slowly, slipping from her sight. She quieted, listening, breathing in short airy gasps. After a few moments he reappeared. He sat on a stool in front of her. He now carried a policeman’s baton. He stroked the hem of her skirt with it.

“I’ll bet you can do lots of things,” he said. “I thought we’d start slowly, being your first time.” He pushed the tip of the baton between her knees. “You were Mandelstam’s whore. Tell me about him.”

She couldn’t speak or think, only wisps of air came from her. He pushed the baton upward a little.

“We don’t have to start slowly, whore.”

“I—I don’t know—I mean, what do you want to know?”

He removed the baton and sat back.

“What was it like—your first time with him?”

She struggled to find words. He looked bored, then he wagged the baton in her face.

“I think you can do better.”

She started again; her vocabulary became more eloquent as she went on. He brightened at first, then seemed to grow agitated as he listened. She stopped, uncertain that she might be upsetting him. He growled at her to go on.

“Tell me what it felt like the first time you put that bastard’s cock in your mouth.”

Her voice seemed to come from a hole behind her head. She went on, feeding him words, words she never used, and his breathing deepened and he started to grimace. He stopped her again and had her repeat herself. Finally, he sprung from the stool and struck her with the bat across her cheek. The walls flickered with pinpoints of light. She had satisfied him.

Each day he questioned her then beat her; afterwards he’d sit awhile until the red of his cheeks faded, until his breathing steadied, until the trembling of his hands subsided. Then Mark would have his turn. Mark was interested in other things.

It was Mark she could imagine as her lover. Shorter and more compact than the sprawling and emotional Matthew, he maintained a stillness in his features during their exchanges. It was only when he would step away, remove his wire-framed glasses, and wipe them carefully with his handkerchief that the silent and muscular John would step forward with a short leather-sheathed bat. Then she knew she’d touched him in some way. She heard her voice exclaim in short beats as John laid into her; each slap against her thighs and buttocks followed by a bright burst in her brain. Eventually he would tire and the cadence would slow and her exclamations would crescendo into round moans. When the beating was finished Mark would fold and return the white cloth to his pocket, slip the glasses back behind his ears, and raise his eyes to her again. He was patient with her; he forgave her these interruptions. She imagined him dressing in the morning, thinking of her as he took each button through its hole, as he looked in his mirror.

Most of the accusations were fabricated. Associations with people she’d never known, conversations that had never taken place, meetings impossible for her to attend as she’d lived somewhere else at the time. She commented to Mark once that his fiction was compelling.

She was told her attitude did not help her. When she returned to her cell, a metal shutter had been screwed over the window. Where the clock had hung there were only wires.

When alone she tried to imagine all they could do to her, the worst they could invent. And when they did something new, she’d return and examine her limbs, press on the bruises, and recall the memory of their specific tools. In the places she couldn’t see, she’d trace the swellings with her fingers.

At night the guards woke the prisoners repeatedly. It was difficult to estimate the passage of time. One morning Mark happened to mention she’d been there for twenty-one days. She’d counted over twice more and with this she cried. For one strange moment he looked apologetic. Puzzled and pained and perhaps in some way embarrassed. As if he had inflicted a wound he’d not intended. The room was silent. Tears took random paths down her cheeks and lips.

Later, after her escorts had returned her to her cell, she imagined the other interrogators ridiculing him for ending the session early that day. She knew the same as he knew: he’d given up a temporary advantage for reasons he didn’t understand. She imagined he’d complain of a headache then retreat to the infirmary for an aspirin.

Usually they talked about Mandelstam. One day, he wanted to talk about Bulgakov. He suggested the topic as if he were suggesting an outing on a fine day. Matthew was home with a mild fever and they’d not yet tied her up. Mark offered her the extra chair. She sat down. Its padding was thin and the underlying curve of its metal support pressed into her tailbone that’d been bruised during their last session. She shifted. She rested her arm on the table. He sat facing her, his arm resting like hers in a mirror image. John stood near the door. She allowed her feet to lie flat on the floor.

Since her arrest, she had wondered if Bulgakov had been taken the same night. She feared for him, that she might implicate him in some way. Sometimes she envisioned him in a nearby cell, staring at the same colored walls, eating the same watery soups and old bread. At night lying on her bedboard she imagined them reunited in sleep, his arm around her waist. Other times, but not at all times, she grieved for his lost work. It was easiest first thing in the morning, after she was awakened. Later, when her interrogators were finished, she cared less for his words. They flitted about her like moths, thoughtless of the difficulties they had caused her. By the next morning though, she felt guilty for this betrayal. As if in the night they had fought their way to the light and by morning their carcasses were scattered on the cell floor, upturned and motionless. She was regretful for such an end to their short lives.

—Let’s talk about Bulgakov

—I’ve heard of him.

—You were found in his apartment.

—I’ve been found in many people’s apartments.

—Do you like his work?

—I’ve never seen it.

She wondered why she aligned herself with writers. Surely men such as her interrogator had come through the doors of the stores where she shopped, the cafes she frequented. She could have smiled at their attempts to tease her name from her; she could have let them take her to the movie theater and buy her flavored drinks. In the flickering darkness she could have let their fingers wander over the seam at her shoulder, move to the curve of her neck. Afterwards, they’d have talked about the movie, the news in the papers, the latest feats of their local Stakhovite. Later they’d have gossiped about their neighbors and friends. The shape of their lives together would form about such things. If she picked up a book to read, she’d give no thought to the writer who’d penned it for her. It might be nice to think nothing of him.

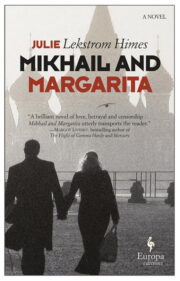

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.