The guard placed his foot on the next step. The interrogator didn’t move.

“Beg me,” he ordered her.

“Comrade Interrogator,” the guard began.

“Shut up,” said the interrogator. “Beg me, whore.”

“They are expecting her back,” said the guard.

“What’s your name?”

He told him.

“Well, Miklosh,” the interrogator immediately applied the diminutive form. “You should make it your job to care about what I care about and not worry about other wormlike guards like yourself.”

“I beg you,” she said.

They both looked at her.

“What’s that, whore?”

“You heard me.”

“I want to hear it again.”

“You’ll have to tie me up first,” she said. Her words were matter-of-fact, as if she was reminding him of a familiar practice; one they’d agreed upon long ago.

The interrogator laughed and set off down the stairs. “And I will,” he said. His words rang from the cement walls. They heard him then shout to someone below and hurry his descent. A lower door opened then shut.

She leaned against the wall. He urged her forward. “Come along. We’re almost there,” he said. Words that might be a comfort under other circumstances clearly were not here. He thought to give some apology for this blunder.

“Listen,” he said. His grip on her arm tightened to the point he thought might be painful; he needed to wake her up. “The writer wants to know of you.”

She was silent at first, as if she couldn’t make sense of his words. “You’ve talked to him? Where is he? Is he here?”

“No—he’s outside. Don’t say anything more.”

She obeyed him. He was surprised by this and almost regretted the command. At her cell block he turned her over to the guards. He could see she was careful not to look at him.

On his way back to D-block, he stepped into the alcove they’d occupied earlier and lit another cigarette. The mist overhead had lifted revealing an empty sky. His hands shook for a few moments, then calmed. A car horn sounded. This calmed him further.

He went to the place where she’d released the earthworm and squatted. He stroked the dirt. It was nowhere to be seen. He heard wings and a blackbird landed on the top of the wall. It eyed him, then toggled its head back and forth.

He removed his hand and stood back from the spot.

The guard learned in subsequent days that she’d been put on the list for deportation to a Siberian camp. Again, his gain of such knowledge appeared serendipitous: a glance at some documents he’d been asked to deliver to another unit. He wouldn’t tell Bulgakov this news. That would’ve been an additional hundred rubles, he reasoned. Besides, what difference would it have made? He’d do better to keep his money.

Bulgakov returned with the beer.

The guard was gone and Ilya sat in his place. Ilya took one of the bottles.

Bulgakov sat down. He wondered what—if anything—had transpired between the two. Or if perhaps the guard had transmogrified in some way. The evening light seemed tricky.

“It’s not that warm,” observed Ilya. It wasn’t clear if he was referring to the drink, or the weather; a reference to the waning year. He tipped his head back and drank. The bottle was half empty when he lowered it again. He delivered his news without preamble.

“She’s been sentenced to eight years. The penal camp of Oserlag. The best I can do is have her processed as a common criminal.”

The bell of a distant streetcar announced its approach.

“That information,” said Ilya, with a touch of sarcasm. “Cost you little to procure.” He indicated the beer.

Ilya got up, leaving the bottle on the bench between them, and took the path toward Bronnaya Street. He crossed; the streetcar passed between them.

Along the street, one after another, the gas lamps were being ignited. Restaurants were opening; people still wandered there. The kiosk which had sold him the beer was closed and dark. The park was empty except for him. It was beyond twilight; darkness filled the spaces between the benches, along the paths, as easily as did the light during daylight hours, yet there was the sense it harbored other things. Those who required their eyes to navigate the world had no business there.

CHAPTER 26

Ilya wanted to tell her himself.

He stood in his office and stared at the photograph of Stalin on the wall. His was different than Pyotr’s: the Great Man’s gaze was slightly lower. One could imagine his domain was more personal; perhaps one’s own particular cares figured there. Ilya looked at his watch. Momentarily they would arrive, the prisoner and her guard, and through the wall he would hear the movement of chairs, muffled words, some fidgeting, then silence. They were always silent while they waited for him. He hadn’t seen her since the day of her arrest and he realized he was anxious. Anxious of her changed appearance. Anxious she would blame him. Did Comrade Stalin have insight to share? Could Father Chairman provide counsel? How did one woo a woman whose sentence one had enacted? Ilya stamped his cigarette into the ashtray.

The reports of her interrogations had been transcribed on papers as thin as onionskin. They lay on his desk in a dainty stack. Young Fedir was fastidious, his language nearly clinical in its descriptions. In the typing, his machine had dropped every “r” to the level of subscript, and it was easy to become distracted from the prose by the undulating waves of print. But then a phrase would find him—the prisoner seemed frailer than usual today; will consult with the infirmary regarding iron supplements. He reread those lines. Did he, he wondered? Had the medics acted on this concern? There was no further mention in subsequent reports. Was there a usual level of frailty that required no action? A subtle shift in the hanging of her dress? Bluish shadows under her eyes that told of malnutrition and sleeplessness? The young interrogator had come to know such specifics and Ilya disliked him for this.

Overlaying the reports was a single page with the recommended disposition. It was the standard text. The prisoner was an excellent candidate for rehabilitation, so it read. She would derive great benefit from Siberia’s robust frontier and the opportunity to make a dedicated contribution toward the strengthening of the Soviet infrastructure. She would learn firsthand of the joy in communal living and the satisfaction of working with others toward the larger purpose.

Ilya traced his fingers downward. Below Pyotr’s signature was a place for his.

He signed such documents every day.

The outer door in the adjacent room opened. Two people entered but there was only the voice of the guard. He’d typically wait as long as a quarter hour, but he could not help but think: She is here. He opened the door. They had just settled into their chairs and immediately they rose.

She was thinner than before. She appeared surprised to see him and this unsettled him. He looked away, not wanting to know more until they could be alone. He’d carried the stack of reports with him. He grumbled of being too harried and pressed for time. He put them on the table; the pen beside them, and took a seat.

“You may leave now,” he told the guard. If the guard felt this was irregular, he gave no indication. He departed and the door closed. Ilya pretended to focus on the reports. He heard the other chair shift as she took her seat.

He turned the pages one by one as if they required some careful inspection. The text rippled across the page; he read none of it. She was silent; not even the wisp of her breath could be heard. There was only the sound of moving paper. He sniffed, then rubbed his brow as though something he read had pained him. He cleared his throat but still said nothing. All seemed staged, only he’d been given no dialogue. He was at a loss as to how to begin. The reports offered nothing. He reached the end and started to page through them again.

Her hand rested on the table. Her skin seemed translucent.

A phrase on the page caught him: The prisoner smells of lavender today, the source of which is inexplicable.

He knew then. She’d not survive that first year in prison. As though she already carried her contagion dormant in her chest, biding its time. Across the steppe, then into the Urals, as roads became trails, then paths, it would awaken. As food and supplies dwindled, as the cold took its turn, the entity would grow. It would break down her tissues and rebuild them to its own specifications. After a time, after much suffering, whatever remained would stiffen in an unmarked grave.

Even in the stale, overwarmed air of his office, this future was as real as if it’d already occurred. Behind her shining eyes, he saw dead ones staring back at him. As if there were two of her, the second in the background, waiting, certainty giving it patience; its turn would come. The hopelessness of the moment rose in him.

“You’re to be sentenced tomorrow,” he said quickly, his voice deepened. “It’s more of a formality, in truth. The decision’s been made.” He pushed the disposition letter forward. He watched her read it. Her expression didn’t change from the start of it to the finish, as if she’d expected it.

She placed her hands in her lap. He had the sense she’d withdrawn not in anger or regret, but rather so as not to taint him. He could not see what she was doing below the tabletop; if she was praying, or wringing her hands in despair. He wanted to take one hand back in his, he wanted to separate it from the other as if apart they’d be easier to persuade.

“How long?” she said. It was the only sound in the room, yet it seemed he strained to hear her.

“Eight years.”

She lifted her hands to the tabletop as the drowning might, as if to steady herself on a piece of flotsam.

He weighed the expanse of this for her. His words were soft.

“This is exile.”

All things she knew and loved, all freedoms both cursed and enjoyed, would disappear. The tips of her fingers whitened where they pressed down.

Those hands would look different after a few months.

“Why wasn’t he arrested?” She asked this without rancor. It was the most natural question.

How could he answer? His frustration with her dissipated a little into a more general disquiet with the rest of the world. Her arrest made his unnecessary.

He tapped the paper. “This doesn’t have to happen. If you give them something, something to indicate you’re willing to work with them, they will make an arrangement instead.”

“An arrangement?”

“Something that happens here every day. Many times a day. For many, such as yourself.” He was given to a vision of Muscovites, thousands of them, walking the streets, looking over their fellow citizens in the stores, in the parks, on streetcars, evaluating their deeds, their words, their hearts. Listening. Always listening. Knowing better than to speak themselves.

“I’d make a terrible informant,” she told him.

It seemed like a small thing, in exchange for her life. “Do you think that you are protecting him?” he said.

Her face held not an answer to this, but a different question. If she took this offering, how was she to return to Bulgakov? Now with the ability to destroy him? With the expectation to do so? Perhaps she’d already envisioned this darker future. Perhaps she thought she was saving herself.

He wanted to tell her that no one escapes these kinds of choices.

She took the disposition letter and reread it. “You can sign this,” she said, as though it was her permission to give.

He didn’t want her permission. He certainly didn’t need it.

“I don’t want to sign it, but I will,” he said. “When you leave this room, when this meeting has ended, I promise you.” His words had become threatening; he wanted her to feel threatened. He got up and paced. Behind her chair, then back again. “This is real,” he went on. He couldn’t see her expression. It was easier this way. “They will load you on a train like livestock. Worse than livestock. Livestock they care about, you they won’t.” There would be typhus. Disease. He would never see her. Did she care about such things? “I won’t be able to help you. Do you understand?” He picked up the pen and threw it across the room. It hit the wall and scuttled to the floor leaving a mark.

“Don’t do this to me,” he said.

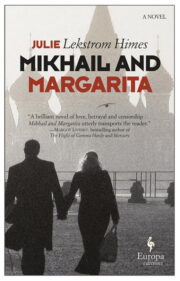

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.