“They never look like criminals, do they?” An older gentleman in a suit and an overcoat of above-average construction appeared to be observing them as well. He looked at Bulgakov as though grateful for one of his kind. It was unlikely this one would give up his ticket.

“Perhaps they’re not,” said Bulgakov. Such a sentiment he would not have expressed openly before.

The man gave no reply. He gestured as if he’d spotted an acquaintance and moved away without explanation.

The prisoners began to jostle each other, rising to their feet. The train whistled. Those waiting on the platform then stood and the prisoners disappeared from view.

Another man, closer to his age and of lesser means, in a cap and factory-produced clothes appeared to be traveling alone. Bulgakov sidled up to him.

“Quite some crowd,” said Bulgakov.

“When is it not like this?” said the man.

“How far are you going?”

The man held out his ticket. Ulan Ude. Bulgakov shook his head as though the man had pulled a losing ticket from the lottery. The man reexamined it then shrugged. His mother was sick; such was his luck.

“That’s a tedious trip,” said Bulgakov. The man reacted little; perhaps he didn’t know the word.

“Boring,” said Bulgakov. The man agreed. He’d brought an extra bit, he said. One could usually find a game if one knew where to look. Several of his teeth were missing, his gums grey above the gaps.

Bulgakov offered to buy his ticket; he told him it was for his brother whose application had been mishandled. The man looked around for the unlucky person and Bulgakov waved generally toward the far end of the platform. This one always pulled the short stick, he added, shaking his head as though it was some unfortunate inborn trait.

“How much are you offering?” asked the man. He seemed both skeptical and greedy.

“Fifty rubles.”

Bulgakov could see he’d miscalculated. The amount was too much and the man relaxed; he sensed Bulgakov’s need and was ready to wheedle. One who would offer fifty could go higher. The crowds around them had thinned a bit. The man scratched his head under his cap. Time was his friend.

“She’s pretty sick,” he said. “What kind of a son would I be?”

“You could send her the money,” said Bulgakov.

“Mail is chancy.”

“Then bring it to her later.” The clusters around each carriage were shrinking. “Come now, fifty is more than fair,” said Bulgakov. The man seemed rooted to the platform. The train called again.

“Where is your brother?” the man asked.

“I have no idea,” said Bulgakov, annoyed. “Come now.”

“Who has a ticket and who doesn’t?” The man wagged his head. Who was the smart one, he would say? This man in a suit and overcoat? I think not!

“Maybe your brother has more?” said the man.

“The ticket is for me,” said Bulgakov. “This is what I have.” He would turn out his pockets if necessary.

The man seemed unaffected by the sudden contraction of opportunity. He kicked lightly at Bulgakov’s shoe. “Those are nice,” he said.

“What would I wear?”

“We could trade.” He pulled up on his trousers to reveal his well-worn pair. Bulgakov accepted and put on the other man’s shoes. The toes of his left foot curled against the stiff leather upper; they were of unequal size.

“Why do you want a ticket so badly?” asked the man. For a moment, his question seemed less about gauging its value. He rubbed the paper between his thumb and middle finger.

On the other side of the platform, the prisoners were being loaded into a boxcar. Two of the guards stood in its opening. One by one, they grasped each woman by the arms and hauled her up. Midair only for a moment, each kicked her legs slightly then struggled to gain the step; some stumbled and caught themselves, others landed on their knees then hands, and Bulgakov was given to the thought of mythical creatures being pulled from the sea into a waiting boat of fishermen; these creatures were trusting of the men, their legs new and strange to them. They would never go back.

“There’s a woman,” said Bulgakov, half under his breath. His brain seemed incapable of producing lies.

The man asked the time and Bulgakov checked his pocket watch. The glint of the timepiece disappeared under the man’s fingers. Bulgakov winced.

“I hope your trip is a tedious one,” said the man. He sounded uncomfortably sophisticated. He departed for the street as though he’d never had any intention of boarding a train. The watch chain dangled from his trouser pocket.

Almost immediately an official appeared, asking to see Bulgakov’s ticket. Then his travel papers. “These are an obvious fraud,” he said indignantly. “Follow me.” He led him to a squat building at the far end of the platform that housed several rooms, only one of which maintained a warming stove. Bulgakov was told he would be dealt with shortly. The official took his papers with him.

The room was empty save a few chairs around the perimeter. The stove had an unpleasantly pitched hum. Bulgakov sat down. Lithographs had been tacked to the walls; they carried familiar slogans: Don’t be a big mouth—even the walls have ears! Another was a quiet scene of Stalin writing at a desk: Stalin in the Kremlin cares about each one of us.

Perhaps Margarita had spent time in a room such as this, waiting, uncertain of her future. He felt calmer for that, as though this room, and his anticipated journey, might be a kind of pilgrimage. He leaned his head against the wall and listened for the train’s departure.

The door opened and a short, diminutively built man entered, dressed in a manner not dissimilar from Bulgakov and carrying a leather valise. He pulled one of the other chairs around and sat opposite him. He had a trace of a smile, one of confidence, as though he’d already predicted his next meal to be a pleasant one. It was clear who was being detained and who was not.

He wet his lips before he spoke. “My name is Pyotr Pyotrovich,” said the man. “I understand you desire to travel to Ulan Ude today. This has become a problem, yes?”

Pyotrovich brought his case to sit on his lap. He withdrew a photograph the size of a standard sheet of paper and showed it to Bulgakov. Its features were made grainy and indistinct in its enlargement. “Do you know this man?”

It was Ilya. Bulgakov nodded.

Pyotrovich produced another. This one was Margarita. It was of better quality. Pyotrovich let him take it.

She’d been beaten. The right side of her jaw was swollen, discolored. Darker matter was near her ear—what else could it be but blood? Her lips were parted as though she would speak to this. But it was her eyes: they stared straight through him. They harbored an expression he’d never seen in her before. He was wholly responsible for this.

“It was taken after her arrest,” said Pyotrovich. He sounded almost apologetic for her appearance. “It was handled poorly,” he added. He took the photograph and Bulgakov’s hands fell lightly to his lap.

Pyotrovich sat back. “We have reason to believe that Ilya Ivanovich is planning to effect her escape.” He paused slightly, perhaps hoping for a reaction, but then continued. “If you help us apprehend him, we will release her.”

Could he believe this? Could such a promise be true?

“Given the dimension of his crime,” said Pyotrovich. “Other things—using fabricated travel documents, securing a train ticket by illegal means—such would be forgivable, of course.”

What did this agent think he could do? Did it matter?

“May I see her once more?” He reached for the photograph.

Pyotrovich seemed to hesitate at first.

Bulgakov studied its shadows, the points of light in her eyes that had captured the flash of the photographer’s bulb. The flatness of the page belied the curves of her face, its texture, in a way that seemed deliberate. Would she describe the ache of bruised flesh? Invite him to touch it himself? Tell of other humiliations suffered? Would she teach him what was worthy of fear? He was willing to learn.

“It is imperative we secure Ilya Ivanovich. He is a traitor.”

It seemed like a gift, only she appeared skeptical. Did he trust this man with the moist lips, the close-set eyes? This one responsible for her battered face?

“All other matters are secondary, in fact,” said Pyotrovich.

Bulgakov perceived the faint sense of opportunity. Not unlike the man who’d sold him his ticket. Someone savvier would negotiate.

He studied her eyes. She wasn’t thinking about him. She might never again. “I’ll do anything,” he said.

Pyotrovich seemed pleased with Bulgakov’s answer. He returned the pictures to the valise. He provided Bulgakov with new papers and a second-class ticket and a story. He was traveling to Irkutsk for the Arts Theater. A fledging provincial theater there required some stewardship; this was as a favor to Stanislawski and wholly sanctioned by the authorities. It was actually plausible. Pyotrovich told him he would be contacted when he arrived.

Pyotrovich reached into his valise one last time and produced Bulgakov’s pocket watch. The gold shimmered white for a moment. “It can be calming to mark the passing of time while traveling across the steppe,” he advised. Bulgakov returned it to his pocket.

It seemed to fill the same space as before, as if nothing about its workings had been changed by its passage through these other hands. It still looked like a watch. It could still provide time.

CHAPTER 29

Margarita arrived at the Oserlag camp in Irkutsk Oblast, near the town of Tayshet, six weeks after leaving Moscow. No one spoke to her for the first day and a half other than to tell her to move along or that she was taking too much time in the latrine. On the third morning her clothes were stolen. She was one of the first to rise with the buzzer, still only sleeping fitfully. The back of her head ached continuously. At that hour, all within the barracks seemed grey: a fine crystalline snow had blown all night and the small, square-paned windows set high under the eaves perfused the room with a steely light. The box which had held her things at the end of her bed board was empty. She closed its lid, confused, then opened it again. Around her, others were getting up, sighing, groaning in the damp chill. She went to open the one assigned to the woman who slept below her but stopped as realization set in. Again she opened her own. She touched its bottom. There was only sawdust in its corners. The other women seemed quieter than the mornings before, as if they were watching, waiting for her response to the deed. But perhaps she imagined this. A sudden gust of wind outside lifted. Soon the second buzzer would sound, instructing them to assemble in lines to go to the dining hall. She wrapped her arms around her torso. All she had was the one thin shirt she wore. She would certainly die here. The wind rose again as if in agreement. On the other side of the barracks came a woman’s laughter. It disappeared, then more whispers. That was what they all wanted. Margarita pulled the thin blanket from her bed and wrapped it around her shoulders. A few bunks away, a woman stopped and looked at her. In the dim light she could make out only her long thin face, her dark eyes, her collected disinterest.

The woman on the bed board below groaned loudly and sat up.

“Who are you?” she asked.

Margarita touched the upper board. It seemed strange she’d gone unnoticed but in truth, Margarita had only the vaguest recollection of those preceding days.

The woman looked at the underside of the board over her head. “Well, you certainly smell better than the last one.” She stood up. She was about Margarita’s age, stocky in build, measurably shorter, with a round face and small eyes. Her skin was pale and chapped from the cold. Her light brown hair had a boyish cut. She squinted at Margarita.

“What’s wrong—goddammit, you’re crying.” She swung her arm as if she intended to hit something but it veered through the air and stopped awkwardly. Her arm was a stump, amputated below the elbow.

“I’m not crying.” Margarita stared at her arm in a way she would not have done in her other life. The woman continued to rant.

“If you cry, you might as well dig a hole and lie down in it.”

“They stole my clothes,” said Margarita.

“Who stole them?”

“I don’t know.”

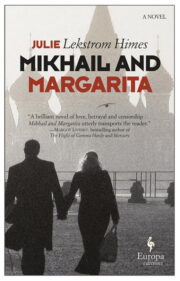

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.