The woman shook her head strangely, then turned and walked up the central aisle of the barracks. As she passed each bunk, she opened other boxes, pulling out garments and gathering them over her arms. Cries of protest followed her and women went rushing to their boxes. Halfway down, she turned around, and headed back toward Margarita. Several women tried to grab back their clothes but she pushed them off. She stood in front of Margarita again, her arms overflowing. A thin, fortyish woman appeared at her elbow. She handed Margarita’s cardigan back to her, then plucked a blouse from the amputee’s arms.

“It was ugly, anyway,” she sniffed at Margarita. A handful of other women came forward for similar exchanges. The amputee dropped the rest on the floor and others reclaimed them.

“I’m a problem-solver,” she said, grinning.

“You’re a cow,” said one of the women, shaking the dust from her slacks as she retrieved them from the floor.

The amputee’s name was Anyuta. She sat across from Margarita at the long benches of the dining hall during breakfast. Women jostled on either side of her, but she refused to budge. She talked while she ate, fixing her gaze on Margarita. It was difficult to focus on what she was saying.

“You’ve got great eyes,” said Anyuta, the way one might compliment something they’d like to borrow. Anyuta dropped her fork on her plate and covered her own eye with a fist. Her other arm moved in tandem as if wanting to mimic its mate. “I’ve got BBs for eyes,” she said. A woman passing behind Anyuta stopped and looked at Margarita.

“Anyuta has a new girlfriend,” she announced. Her tone was mocking yet there was something else about her expression. The woman raised her eyebrows, then left. Anyuta didn’t say anything but continued eating. A buzzer sounded. She reached across the table for Margarita’s plate.

“I’ll take that.” She stacked it on her own without waiting for an answer and carried both dishes away.

After their meal, the prisoners boarded a bus. The exterior of the windows had been painted in whitewash. Anyuta moved in behind Margarita in line. As they came down the aisle, she grabbed Margarita’s arm, propelled her into an empty seat, and sat down beside her. Margarita studied the window. In places, she could see the blur of dark objects. A car, the building beside them, the vague movements of people. Bubbles in the wash had flaked away leaving scattered pinholes. She leaned closer to peer through them but saw only crisp fragments. Ahead, the windows around the driver were clear. She lifted up to look but was suddenly blocked by the head of a woman who sat down in front of her.

“There’s not much to see,” said Anyuta, almost apologetically. “Just a chickenshit town.”

Were they going to the town?

Anyuta shook her head. To the factories beyond. They were building dormitories for the workers.

The bus began to move. Shadows passed across the white blur.

“What’d you do?” Anyuta’s voice was close to her ear.

At first Margarita thought she was asking of her occupation.

“My sister’s husband died,” said Margarita. “I tried to sell his clothes on the black market.” She’d made up this story before arriving at the camp. “We needed the money.”

Through the window dark shapes flickered across the paint followed by stretches of only white. Forests and fields? She began to feel queasy and closed her eyes.

“I’m sorry about your sister’s husband,” said Anyuta.

Margarita turned back to her. Anyuta had been staring at her hair; she averted her eyes. In the white light cast by the wash, she seemed more acutely weathered than before.

Margarita asked why she was there.

Anyuta made a face.

“My father was a kulak,” she said. She smiled suddenly. “Do I look like a kulak’s daughter?” She studied the window as if watching a scene unfold. The empty sleeve of Anyuta’s jacket was partially collapsed; its end was folded over and fastened with a straight pin. It rested against her trouser leg opposite its fuller mate as if unaware.

She made a sound like a small sigh.

“He’d take me fishing,” she said. “I was small and afraid of their teeth.” She shook the empty sleeve. “He’d pull the hooks from their mouths, then he’d string them on a pole and carry them to the village. He’d call on everyone to admire ‘Anyuta’s catch.’ As if he was proud.” She glanced at Margarita. “I was bothersome for my mother. I talked too much.” She smiled. “I still mind their teeth, you know.”

The bus slowed and the forms through the window took on angular shapes. Buildings. A car. This was the town. Moisture from the breath and perspiration of so many bodies had condensed on the inner surfaces and with the slowing of the bus, voices from the prisoners behind and in front of them began to lift in protest to the stifling air. On both sides, arms went up and windowpanes were dropped down. Crisp snowy images of brick and planking and glass darted past. A brief chorus of gladness rose up as the cold whiffled through the bus. The guard who sat next to the driver came down the aisle waving a baton from side to side and ordered the windows shut.

“No one’s supposed to see us,” said Anyuta.

In his wake, from the front to the back, the windows rose up again. Margarita half-stood and watched as the world slid away. Once they were closed, she sat down. Rivulets of water now streaked across the glass. The air was cold and damp.

She’d heard of prisoner jobs in the towns, outside the camps and the typical work sites. Jobs with less supervision. She would have to get one. She would have to be seen as trust-worthy. She studied the empty sleeve beside her. Perhaps Anyuta could help her. Anyuta the problem-solver.

“Is it hard to get a job in the town?” she wondered aloud.

There were always such jobs, Anyuta told her. The people who took them would try to escape and get caught. She held up her hands as if firing a machine gun. “Ch-ch-ch-ch-ch,” she said, sweeping it at the seat in front of them.

The woman across the aisle looked at Anyuta then away as quickly.

“They always get caught,” Anyuta repeated. She touched Margarita’s sleeve. “Don’t get caught,” her BB eyes pinned her back. “Ch-ch-ch-ch-ch,” she warned.

CHAPTER 30

In the summer of 1826, Prince Sergei Volkonsky and the other Decembrists walked six thousand kilometers from St. Petersburg to the silver mines of Nerchinsk, a penal colony near the Russian-Chinese border. One foot of each man was shackled to the same-such foot of the prisoner preceding; the alternate foot was chained to one in the rear of him. Thusly, in lockstep, they came to know each weedy hillock, each crusted rut of the road that was Levitan’s Vladimirka. The Russian steppe extended an indecipherable distance in all directions until it met with the towering sky. There it formed an encircling seam of which they were forever captive, low and at its center. After the second week, they rarely looked beyond the edge of the road and when they did, it only served to renew their utter despair for the years that remained of their still young lives. There could be no better prison, said Volkonsky to his friend, Prince Sergei Trubetskoy, chained to his rear. No stone wall could so completely extract all hope from a man’s breast. Trubetskoy did not respond. The failure of their revolt, their failure to wrest from the Tsar even those most modest concessions for representational governance no longer caused him to wonder. Indeed, how could the Tsar, no different from any Russian, understand freedom, trapped in a land that went on forever yet never changed?

Ilya said nothing when Bulgakov first opened the door of their shared compartment. He’d been reading the paper; it came to rest in his lap as Bulgakov struggled to enter with his luggage. It seemed to Bulgakov that he himself was the more surprised. He consulted his ticket. He was in the correct berth. How was he to explain this cosmic alignment?

“This isn’t entirely coincidental,” said Bulgakov. He shut the compartment door. “When you told me of her destination, I immediately requested relocation to a nearby town.”

“Have you been to Irkutsk in January? You may rethink your fortune.” Ilya resumed his reading. He seemed too accepting of this happenstance and while he may have found Bulgakov’s explanation absurdly thin, he did not appear to consider him a threat.

The compartment was small and clean, though there was a musty odor. Its walls were paneled in honey-colored wood. Two benches faced each other with a short table between. The longer of the two would serve as a bed; above it, a narrow door concealed a second berth which could be prepared as well. The window was hung in velvet drapes; beyond, a wintry Moscow rushed by. The train jerked suddenly and Bulgakov reached for the wall beside him.

If Pyotrovich could detain Bulgakov on the platform, why would he let Ilya proceed? “Aren’t you afraid of being caught?” Bulgakov asked. He’d lowered his voice.

Ilya paused before answering. “There is no crime in riding a train.”

Pyotrovich would want to catch him in the act, convict him of the greater crime.

“I’m visiting my brother,” said Ilya.

“I wouldn’t have guessed you had a brother.”

“He would likewise be surprised.” Ilya shook his head at the page as though amused. “It seems a company of workers, led by an up-and-coming Stakhanovite, worked for days on end to surpass all timelines for the laying of pipes between a reservoir and their town’s cisterns. Unfortunately, they connected the lines to a sewage tank. Thousands were sickened.”

“There may be opportunities to visit her,” said Bulgakov. “I’ve heard such can be true.”

“I’m surprised this was published,” said Ilya, frowning at the byline. “Stupidity is not generally a problem here. Ah—of course—he was revealed as an enemy of the People. Wreckers we have by the thousands, idiots nary a one.”

“I’m willing to wait for her,” said Bulgakov.

With this declaration, Ilya reassessed him. His expression seemed something akin to sympathy. He raised the page again, as though to hide it.

“I can ask the porter about moving to a different compartment,” said Bulgakov.

“There is no need,” said Ilya.

Bulgakov recognized the suitcase on the rack above; the one with the hidden compartment. It seemed then there were three of them traveling together: two men and their shared purpose. The newspaper fluttered slightly. After a while, there came the sound of snoring.

Beyond the outskirts of Moscow there were provincial towns. Beyond these were villages strung along the rails, some with only a handful of unpainted huts. Occasionally and in a seemingly arbitrary manner, the train would stop and allow its passengers to disembark. Older folk, women mainly, clad in layers of shapeless black cloth, waited on the platform with baskets of prepared foods at their feet. Bulgakov tried to engage them with simple questions, of their livelihood, their families. They answered by indicating with their fingers the number of coins required for a sampling of food. As if it was inconceivable they might share the same language of the travelers. Bulgakov wondered of the content of their days when the rails were quiet. They wouldn’t wonder of him, he knew, as though, like his language, his life was impossible to comprehend. After a day even such scraps of civilization were gone and there was only hour after hour of empty steppe.

It was difficult to focus one’s thoughts in this landscape. Bulgakov tried to imagine the future with no more ambition than to conceive of an upcoming meal and found this nearly impossible. Thoughts drifted into the undergrowth of the past. He ruminated on his first clinical appointment in the year following medical university, assigned to a village that offered little more than those they’d passed. He could remember none of his successes, only those who had succumbed in spite of his efforts. He might say their spirits visited him, but in truth, he was the ghost who went to their bedsides, interrogating those moments of indecision and exhaustion, of gross ignorance and utter inexperience. He was young then. He knew better now of grief. He was sorry then, but perhaps not sorrowful. That was his sin and he returned to it again and again.

The drone of the rails was unending. Vibrations from the churning wheels gave even fixtures of steel and wood the look of animation. Beyond their window, the interminable expanse of crumpled earth took the form of the multitudes who had perished there: centuries of dead entombed, from insect and fire, disease and famine, from tyrant and infidel, layer upon layer, bones thinly veiled by the grassy sod. This vastness was their monument.

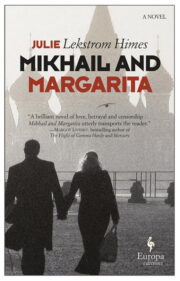

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.