“The Enhancement Committee meeting has been moved to Room 24,” said the assistant. He gestured with his free hand, over his head.

“Has Berlioz returned?” said Bulgakov.

“He extended his holiday by a month.” The assistant appeared neither dismayed nor surprised by this.

“And the Acting Chair?”

He repeated his earlier gesture, then went back to his writing. Bulgakov settled into a window ledge as a makeshift seat. It seemed safer somehow; his escape route, no matter how precarious, at his back.

Over the course of the next three quarters of an hour, a half dozen others joined them. Some took refuge in the window casings as he did; others sat somewhat uncomfortably around the table. One asked another the time, then, after receiving an answer, checked his own watch. Bulgakov was about to leave when Margarita came in. Her eyes flicked over him and he was left with the immediate impression that despite whatever secret they might share from that other morning, she was skeptical of his motives, perhaps wondering herself why she’d bothered to deliver the note.

The acting Chairman entered: Leonid Beskudnikov, an essayist who specialized in historical pieces. He directed his first question to the rightful Chairman’s secretary, asking if there was yet any word of the other’s return. The reply was the same as before and the essayist looked visibly uncomfortable. “What are you doing?” he asked sharply of the secretary, as he appeared to be writing with great energy.

“I am minuting your meeting,” he said. Beskudnikov’s discomfort went to the extreme. “I don’t know if you can call it my meeting,” he said. “This seems more of an informal gathering. Quite informal.” He searched the room for agreement.

The novelist Poprikhen, an amply sized man, leaned back in his chair. He appeared neither unhappy nor frightened. “Do we know exactly what Mandelstam did?” he asked the general audience. Others leaned in, hopeful of gossip. “Maybe he deserved it,” he said. “I think that should first be established.”

“Seems like it’s always the poets,” sighed Natasha Lukinishna, a diminutive woman with round glasses, who wrote naval stories under the pen name Bosun George. “What else can they write about except how unhappy they are with the world?”

Poprikhen wagged his finger at the others around the table. “Not everyone is a saint and it’s not always the wrong person who is detained. They must get it right sometimes.” With this, several began to talk simultaneously. Beskudnikov held up his hands but was ignored.

All conversation stopped. Nadya entered, accompanied by the poetess Anna Ahkmatova. Both were in black. Anna’s hands were clasped around Nadya’s arm, but she looked to be the one in need of support. Nadya’s posture, and in fact her entire demeanor was poker-like, while the otherwise stately Akhmatova was as bedraggled as a refugee. Beskudnikov rose, followed by the others; the women sat near the head of the table and the rest resumed their seats. Their effect was funereal. Everyone avoided making eye contact and struggled to find something to look at besides the two women. After a few moments, however, no one could unfasten their eyes from them. Nadya seemed impervious, staring into some unseen world.

“Have you had any news of your husband?” Beskudnikov asked.

She took an inordinate amount of time to answer. “I’ve heard nothing specific,” she said. Her fatigue was palpable. She told them she’d met with Bukharin three times. The third he’d asked what she knew, admitting he knew nothing more. The fourth he’d refused to see her. Someone with connections to the Secret Police asked her the rank of the agent who’d searched their apartment; evidently the higher the rank, the more serious the case. Another had made inquiries on her behalf, then was advised not to get involved. “I wait in line,” she said. “I leave packages daily—I have no idea if they make it into his hands. I have no idea.”

“Of course we want to do something,” said Beskudnikov. He looked at the others, summoning a tone of chairman-like magnanimity. “We’ve discussed a collection—food, perhaps.” He paused to judge her reaction to this. “Or prepared meals might be better. Someone suggested a collection of money.” From a spot around the table came a noise of concern and he added, “Of course, for the needs of the household, et cetera; any monies from the Union couldn’t be used—not that you would engage in illegal activities, but you understand, there can’t be the perception that the Union has funded anything untoward—not that you would consider such things.” He began to repeat himself, his tone weakening. Others in the room seemed to retreat from him as well.

Nadya readied herself to speak. Beskudnikov stared at her lips as though they were perilous things.

“Thank you,” she said evenly.

He seemed to register her lack of loquaciousness as disappointment and his fearfulness shifted again. “Of course, we could do more,” Beskudnikov went on. “We should do more. We could.” He searched the room for agreement.

Clearly they knew nothing about the poem, Bulgakov thought. If they did, such a meeting would have never convened. He was annoyed; there should in fact be two Unions—one for those who were actually writers and another for people who simply placed words on a page. Mandelstam had stepped forward. He’d sacrificed in defense of all of them. Yet they would call it something else. They would assign it a different motivation—discontent, naïveté—to make their lack of action defensible.

“The Union could pen a letter to the editor,” he suggested. “A formal protest—Pravda would be best. It’s read by the world.” Those with their backs to him swung around in their chairs. Beskudnikov appeared to be seized by terror.

“You, of course, would be its author,” Bulgakov went on. “As the Union’s Chair.”

“Only the acting Chair, you understand. Something of this nature should really come from Berlioz, I believe.” He’d gone pale.

“Who knows when he’ll return—that could be too late.”

Too late for what? The gathering seemed to register his words with a kind of belated understanding; several glanced at the door as though thinking to leave.

Poprikhen shook his head with grave significance. “I don’t see how a letter can be fashioned if we don’t know exactly what he’s done. What are we to protest? This all seems quite ill-conceived.” He glared at Bulgakov.

“He wrote poetry,” said Margarita.

“Well, there it is,” retorted Poprikhen nastily.

“I’m not certain your opinion matters here,” Beskudnikov added faintly to Margarita. “It’s not entirely clear why you are here, seeing as you are not a Union member.”

Bulgakov had some vague recollection she wrote for one of the daily newspapers. They had their own union, of course. “She’s with me,” he said quickly.

Nadya’s gaze shifted to him. Her face was impossible to read.

“Regardless,” he went on. He stumbled for a moment. “Regardless—of whatever he did, do we allow even one of our members to be arrested for the act of self-expression? Otherwise we might as well invite monkeys to come in and do our job.”

“I agree,” interjected the dramatist Glukharyov from the corner. “So they don’t like what he writes—they’re allowed not to like it. Censure him, censor his work; but arrest? Are we now back to the practices of the Tsar and his thugs?”

There was a clamor of voices, then Poprikhen’s rose above it. “You know what Mandelstam writes—we’d be fools to align ourselves under that banner.”

“And if you were to be arrested,” said Bulgakov. “The rest of us should sit back and collect canned fruit for your wife and family?”

Beskudnikov began to protest but Poprikhen’s retort pushed him back. “There is precious little chance of my arrest,” he growled. More than one Committee member considered himself the novelist’s patron.

“Indeed, what a grand loss it would be for Soviet literature if you were,” said Bulgakov.

Poprikhen gave a wordless roar and attempted to launch himself toward Bulgakov, though he became entangled with his chair. The din rose until Beskudnikov stretched himself over the beet-faced novelist, essentially sitting on him and preventing the match of words from becoming a fistfight. The secretary continued to write, madly flipping pages and wiping his sweating brow. “Stop it!” cried Beskudnikov, to no one in particular. Eventually the room quieted. Gingerly he dismounted from Poprikhen’s lap and resumed his seat.

“Stop it,” he repeated, though the room was now silent. He adjusted his suit jacket. “There will be a box, placed in the foyer downstairs for the collection of foodstuffs, for the Mandelstams. In the meantime,” and he stretched his neck as though recovering from his recent gymnastics, “Comrade Bulgakov will draft a formal letter with some representative suggestions. This committee will review it in one week’s time.” With that, he stood and fled the room. The secretary remained at the table, still scribbling.

Others filed after him. Poprikhen extracted himself from his chair and slammed it under the table. “You are stupid to make enemies,” he said to Bulgakov.

“Better that than to be plain stupid,” said Bulgakov after him. The novelist seemed not to hear.

Nadya and Anna departed and the rest of the room emptied, except for Bulgakov and Margarita. He wondered what he’d been thinking. Perhaps he should follow Beskudnikov down the hall and beg off his assignment. He had edits to complete, a director to satisfy. Margarita considered him with what seemed to be the same skepticism as he felt. He thought to tell her that her suspicions were well founded

“You were right to say what you did earlier,” she said. She appeared almost sympathetic to him. As though she understood his anxiety, his desire to retreat as the others had. As though she could forgive him for this and would offer a parcel of her own faith to feed his courage.

For the first time that evening, perhaps since the arrest, his furtive need to hide lessened.

She didn’t move, studying him. “I’m not with you, though,” she said, strangely gentle, almost amused in her correction of him. “On that point, you are wrong.”

But she could be, he thought. She might be. And with this a different kind of fear overwhelmed him. He felt the night air at his back. The heat of her presence pressed against him like a hand to his chest.

“You’d probably survive the fall,” she observed easily, as if aware of his impulse. Or perhaps at the spark of a thought to dart across her brain: that she herself might push him.

But she turned and left. And for the briefest moment, the evening became infinitely less satisfying because of his survival.

Mandelstam stood in a grey concrete cell in a shallow pool of water tinged with his blood and urine, his hands shackled to a rope that hung from the ceiling, his feet chained to the floor. He’d not slept for what he thought had been several days. A series of guards watching him from a slot in the wall saw to that. Behind him, beyond his view, the door to his cell opened. The chief interrogator, an assistant, and a smallish man carrying a pad and pencil entered. Typically, it was this last one, the stenographer, who would collect the confession; however, this was unnecessary. He was there to collect names; already he’d amassed a good number. Mandelstam waited. A rubber mallet sailed up between his legs. His knees buckled; his shoulders seared in pain. He heard screams. Slowly he found his feet again. Beating him had been easy for the interrogators; their fists rose on the updrafts of his words. He had been poetic in his venom for their beloved leader; they were now poetic in their rage.

Vomit and perspiration stained his shirt. The stenographer sat down in the only chair in the room and waited for the crying to subside.

Mandelstam heard a gentle scratching. He couldn’t make sense of the noise. It seemed the room rustled with insects. He wanted to listen, to decipher their language.

Pain exploded again in his genitals. The insects fled screaming.

Then: “Mikhail Bulgakov,” said Mandelstam. The scratching returned.

CHAPTER 4

One of the poems Margarita found at the Mandelstams’ apartment had been written about her. She’d kept it apart from those she’d given to Bulgakov. She recognized the early draft, different from the published one. It was an early version of his love.

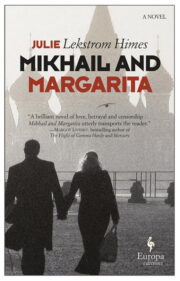

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.