She looked at him as though he’d spoken aloud. As though she was challenging him. At least she hung hers on a wall, she could say. Where an icon belongs. What about his faith? What did he believe in? Was it buried in some play about a sixteenth-century playwright?

The boy in her arms sucked on two fingers and stared at him. He seemed curious rather than fearful, too old to be held in such a manner. The boy took his hand from his mouth and reached for him, catching hold of his cheek as though for the purpose of inspection. Bulgakov felt the stickiness of saliva on his skin. The boy’s smile widened to reveal the gap of his missing upper teeth. A man’s voice came from another doorway further down the hall.

“May we see your papers, Citizen?”

They thought him some kind of official.

“Did someone else come through here just now?” he asked. He avoided a presumptive tone. He tried to ask as though he was himself lost.

“Intelligentsia.” The whispered sneer came from behind, from the walls. Were there others he could not see? Listening through the plaster? Apartments overflowing with the displaced and the poor? He’d heard Stanislawski speak of them; they filled his theater each night. They had come from the villages and farms at the height of the famine. They were wanting in the knowledge of the use of cutlery and soap. They were curious. Curious and distrustful.

The boy had removed his hand and now both arms were wrapped around his mother’s neck. He pressed his head into her chest. He seemed childlike again. The woman stepped inside her door and closed it until only her face could be seen.

“Why should we tell you anything?” she said.

“He might be dangerous,” said Bulgakov.

“Your papers?” the man repeated. “It’s within our rights.” He was likely the local Housing Chairman. The woman opened her door slightly. The boy was no longer in her arms.

The woman turned to speak to the boy; she told him to go into the other room.

Down the hall there was movement from others. Bulgakov’s escape seemed less certain.

The woman opened her door further.

“Perhaps you are the dangerous one,” she said. She sounded more confident. “Perhaps you should be reported. How can we know the difference?” She seemed to think she knew.

Bulgakov’s skin prickled. “Just tell me if someone else came through here before me—tell me who they are?”

Someone tugged on his watch chain. An old man, hairless and pocked, had crept beside him.

“Nice,” he said of it. He rubbed it between his fingers. He had no teeth.

“A gift from my mother,” said Bulgakov.

The old man pouted, clutching the chain. “I didn’t have a mother,” he said.

Bulgakov was about to correct him: everyone has a mother. Something stopped him. Further down were others, invisible before, now creeping forward, growing bolder. Behind was the same, as though to block every exit.

Who were these people, all at once vain and pitiful, self-important and distrusting? Were these for whom he wrote? They seemed ready to rise up from the gallery and take the stage in their name as if it were a battlefield. To take it apart if they chose. It wasn’t that they might fail to understand the subtleties of his metaphor or be lacking in interest. They understood. They were interested. They proclaimed themselves both judge and executioner.

“He’s a spoiler,” said one.

He felt hands encircle his arm. “Why don’t you stay with us?” said another. Someone snickered with this.

Bulgakov passed through them roughly and came to a short flight of stairs, then upwards to the outer doors that provided an exit to the front of the building. The sun was bright and momentarily everything was washed in white. The street was as before; no one showed any particular concern with him. A man passed on the sidewalk; then turned sharply and took him by the shoulders.

“You!” the man spoke with great enthusiasm. “You are Bulgakov! Are you from my neighborhood? I had no idea you were my neighbor!” He looked around as though there might be others to introduce him to, but the sidewalk was empty. The man was now pumping his hand. He said he was a writer as well. Bulgakov vaguely recognized him from the Union. He clasped Bulgakov’s shoulders again; he seemed intent upon maintaining some kind of physical contact. Bulgakov was relieved and grateful; it felt as though he’d been plucked from the depths.

“I heard about what you said,” said the writer, he lowered his voice a little. “At the Union. To Beskudnikov and the rest of those hens. It needed to be said. But come—” he resumed his former tone. “May I buy you a coffee? You’ve already had breakfast?—I see.” He looked temporarily disappointed as Bulgakov shook his head.

“It’s a terrible business about Mandelstam, terrible,” said the man. “One of our greatest poets—the man should be treated like a treasure. I suspect they get a bit overzealous at times—who knows? Perhaps they have some quota they’re required to fill—I’ve heard that. They just need to be made to see reason. Everyone one can be made to see reason.”

The sidewalk around them was empty. This man’s presence seemed uncomfortably convenient.

He went on. “Say, my mother lives just around the block. She’d love to meet you. Do you suppose?” He grabbed his arm again, as though he might drag him there.

“I should get on,” said Bulgakov, trying to pretend amicability. “You’re very kind, though.”

“Not at all!” He continued to hold onto Bulgakov’s arm. “They act as if they’re afraid of him,” he said. “It’s all quite nonsensical. They need to see reason.”

Bulgakov pulled away. “I’ve held you up. I should let you go—you must have other matters—I’ll let you go.”

Bulgakov crossed the street without bothering to look. A car was required to brake and honked in protest.

The other man was still on the sidewalk, watching him. He called out cheerily, “It was wonderful to meet you.”

Bulgakov studied him from the other side. He thought he’d recognized him from the Union, but had he? It was hard to tell from that distance and it was a nondescript face. “What is your name again?” shouted Bulgakov.

The writer waved, but didn’t answer, and Bulgakov wondered if perhaps this was the man he’d been following in the first place.

Initially the agents knocked on the wrong door. The older neighbor averted his eyes and redirected them with a crooked finger. The agent leading the team was annoyed at their sloppy intelligence. When they knocked next on Bulgakov’s door, they waited not at all before he gave the command to just open it. The one that first entered commented on the high ceilings. So hard to find in the newer buildings going up now in Moscow.

A criminal waste, growled their leader. He swept his foot along the skirt of the armchair. He took a book from the bookcase, opened it in his hand briefly, then tossed it aside. He waved the others further into the apartment, then swept the entire shelf clean. Books clattered into a heap. A packet of papers toppled forward to rest flat on the shelf. He took it and seated himself in the armchair; he crossed one leg over the other in a somewhat delicate manner and began to read through the pages. Across the room, the drawer from the bed-table rang out as it hit the floor.

Bulgakov lived on the top floor in the corner apartment of a repurposed nineteenth century house that had once belonged to the paramour of the Dutch Vice-Consulate to Russia. His particular space, at one time the modest spare dressingroom of its former occupant, was oblong in shape though still had good light and was of sufficient size to fit the Moscow code for the standard housing allowance without requiring some crude refashioning of partitions or walls. The room formed itself into two spaces by a decorative archway that spanned the narrower of the two dimensions. The larger space was beyond this division; here Bulgakov’s bed fit into the far corner, next to it a small side table with a single drawer; its spindle legs were obscured by multiple stacks of books. On the wall a modern utilitarian sink had been added later and with remarkably poor workmanship. The newer plaster used to fill the oversized hole lacked the creamy texture of the original walls, and was perpetually collecting on the floor in irregular powdery piles. No effort had been made to repair the wall below it. Since Bulgakov had lived there, the spigots hadn’t produced a drop and he suspected the pipes were never connected. A table with chairs sufficient for two, or in a pinch, three, if the third was willing to sit on the bed, was pressed against the wall. On the other side of the arch, nearer the door, a short sofa with an armchair made up a small sitting area with a squat table between. Bookcases stood on both sides of the chair. These were filled and double-layered, with yet more books in varying stacks on the floor in front, as if waiting in queue. Squeezed between a bookcase and the archway, a narrow wardrobe fought for space.

Few remnants of the room’s previous Dutch life remained: the floorboards along its perimeter were finished with a row of Delft tile; each square was slightly larger than a woman’s hand, painted in shadowy blues and baked in the kilns of that famous factory town. Each was a quiet and singular scene of bucolic seventeenth century meditation without repeat. By some miracle of neglect or more likely ignorance, not a single tile was missing or damaged save one. As if with the thoughtlessness of a blind scalpel, the piece had been parted in two with a gentle curving swipe, leaving behind a young Dutch maiden, holding in her hands the strand of pearls she wore, extended upward, to show to her vanished partner. Another maiden? Her mother? Some young man who’d come to woo her? She was forever alone, her gaze held captive by those opalescent whorls now long divorced from their meaning.

When the agent had finished reading, he leaned forward in the chair; the collection of papers in his hand he’d rolled into a baton. The rest of the apartment was unrecognizable. His gaze came to light on the fragment of tile along the baseboards. A remnant of another time; so many clung to these kinds of things. He rubbed his eyes. What was the take, he asked of the others, as if tired of it all.

Numerous manuscripts. Poems from the poet Mandelstam. A few letters. In truth, little of interest.

“Good,” he said. He stood and slipped the roll of pages into the side pocket of his raincoat. One of the agents asked if he’d like to keep the poems. “No thank you,” he said, his hand loosely touching his coat pocket.

He told them to wait for the writer’s return.

Bulgakov’s first impression when he entered was that his apartment had been quite suddenly enlarged. The walls were bare and open and very white. Then he saw the books were gone from their shelves, the prints from the walls. They lay thick on the floor, like ancient tiles pushing up and sliding over a shifted landscape. Two agents waited, dressed in dark suits, one sitting in his armchair, another on the sofa. It was impossible to tell for how long. First one stood, then the other.

Bulgakov asked if he might leave behind a note, a possible explanation. But he stopped there; he didn’t want to suggest that someone in particular might be looking for him.

The agents told him no and for a moment he was relieved by their answer.

They nodded toward the door and his relief disappeared.

CHAPTER 7

In the fall of 1917 Nadezhda was pretty and slender, with large dark eyes and good skin on which she prided herself. She worked as one of the typists on Stalin’s armored train. She’d bully him when he came back to their car with his revisions and corrections. She called him the Great Man; she’d complain of his handwriting, his atrocious grammar, the things she had to put up with. The other girls would giggle and watch them together. She’d smile and lean toward him. They were old family friends; she’d known him since childhood when her parents had sheltered him during one of his escapes from Siberian exile. He gave his work only to her. “Perhaps you can teach me,” he’d say, and wag her chin between his fingers. She was sixteen and living away from her mother, filled with purpose and unafraid. She saw how the men feared him; her fearlessness placed her above them.

At night, however, when they worked alone on his speeches or his party communications, she was all business. “You alone I trust,” he told her. One night he tried to kiss her. He’d come for the latest revision of a memorandum; she rose from her chair and handed it to him. The last several changes had simply been the rephrasing of a single sentence; he’d gone back and forth with it. She’d made the changes without complaint; the preponderance of evidence of their crimes against the people calls for the execution of these four men. In the alternative version, there were four men and a woman. The tapping of her keys took a life then gave it back. She watched him read over the words. The car was dark except for her desk light; he held the page under it. The train lurched and she swayed. He commented on the hour, how she must be so terribly tired. He brushed his hand over her head, her hair, seemingly with absentminded affection. She told him she was fine. It pleased her to be a help. To him with his important work. With her words, he turned to her, lifted her face, searching for her lips with his. She stepped back with surprise and his groping became awkward. He stepped toward her. Her legs pressed against the desk behind her. The lamp clattered against the typewriter, shining light across the room. She panicked and turned her face away and he kissed her cheek. He stepped back and wagged his finger at her.

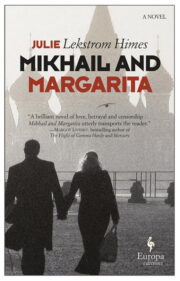

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.