Belatedly realizing that she had somehow blundered into dangerous territory, Valerie made a hasty strategic retreat to safer ground. "I meant only that you are known to be a close friend of both ladies."

Nicki accepted her peace offering with a slight nod and allowed her to retreat in dignity, but he did not let the matter drop completely. "Their husbands are also close friends of mine," he said pointedly, though that was rather an exaggeration. He was on friendly terms with Stephen and Clayton Westmoreland, but neither man was particularly ecstatic about their wife’s friendship with Nicki-a situation that both ladies had laughingly confided would undoubtedly continue "until you are safely wed, Nicki, and as besotted with your own wife as Clayton and Stephen are with us."

"Since you aren't yet betrothed to Miss Skeffington," Valerie teased softly, pulling his attention back to her as she slid her fingers around his nape, "there is nothing to prevent us from leaving by the side of this maze and going to your bedchamber."

From the moment she'd greeted him in the house, Nicki had known that suggestion was going to come, and he considered it now in noncommittal silence. There was nothing stopping him from doing that. Nothing whatsoever, except an inexplicable lack of interest in what he knew from past trysts with Valerie would be almost exactly one hour and thirty minutes of uninhibited sexual intercourse with a highly skilled and eager partner. That exercise would be preceded by a glass and a half of excellent champagne, and followed by half a glass of even better brandy. Afterward, he would pretend to be disappointed when she felt obliged to return to her own bed "to keep the servants from gossiping." Very civilized, very considerate, very predictable.

Lately, the sheer predictability of his life-and everyone in it, including himself – was beginning to grate on him. Whether he was in bed with a woman or gambling with friends, he automatically did and said all the proper – and improper – things at the appropriate time. He associated with men and women of his own class who were all as bland and socially adept as he was.

He was beginning to feel as if he were a damned marionette, performing on a stage with other marionettes, all of whom danced to the same tune, written by the same composer.

Even when it came to illicit liaisons such as the one Valerie was suggesting, there was a prescribed ritual to be followed that varied only according to whether the lady was wed or not, and whether he was playing the role of seducer or seduced. Since Valerie was widowed and had assumed the role of seducer tonight, he knew exactly how she would react if he declined her suggestion. First she would pout-but very prettily; then she would cajole; and then she would offer enticements. He, being the "seduced," would hesitate, then evade, and then postpone until she gave up, but he would never actually refuse. To do so would be unforgivably rude – a clumsy misstep in the intricate social dance they all performed to perfection.

Despite all that, Nicki waited before answering, half expecting his body to respond favorably to her suggestion, even though his mind was not. When that didn't happen, he shook his head and took the first step in the dance: hesitation. "I should probably sleep first, cherie. I had a trying week, and I've been up for the last two days."

"Surely you aren't refusing me, are you, darling?" she asked. Pouting prettily.

Nicki switched smoothly to evasion. "What about your party?"

"I'd rather be with you. I haven’t seen you in months, and besides, the party will go on without me. My servants are trained to perfection."

"Your guests are not," Nicki pointed out, still evading since she was still cajoling.

"They'll never know we've left."

"The bedchamber you gave me is next to your mother's."

"She won't hear us even if you break the bed as you did the last time we used that chamber. She's deaf as a stone." Nicki was about to proceed to the postponement stage, but Valerie surprised him by accelerating the procedure and going straight to enticements before he could utter his lines in this trite little play that had become his real life. Standing on tiptoe, she kissed him thoroughly, her hands sliding up and down his chest, her parted lips inviting his tongue.

Nicki automatically put his arm around her waist and complied, but it was an empty gesture born of courtesy, not reciprocity. When her hands slid lower, toward the waistband of his trousers, he dropped his arm and stepped back, suddenly revolted as well as bored with the entire damned charade. "Not tonight," he said firmly.

Her eyes silently accused him of an unforgivable breach of the rules. Softening his voice, he took her by the shoulders, turned her around, and gave her an affectionate pat on the backside to send her on her way. "Go back to your guests, cherie." Already reaching into his pocket for a thin cheroot, he added with a polite finality, "I'll follow you after a discreet time."

Three

Unaware that she was not alone in the cavernous maze, Julianna waited in tense silence to be absolutely certain her mother wasn't going to return. After a moment she gave a ragged sigh and dislodged herself from her hiding place.

Since the maze seemed like the best place to hide for the next few hours, she turned left and wandered down a path that opened into a square grassy area with an ornate stone bench in the center.

Morosely, she contemplated her situation, looking for a way out of the humiliating and untenable trap she was in, but she knew there was no escape from her mother's blind obsession with seeing Julianna wed to someone of "real consequence" – now, while the opportunity existed. Thus far all that had prevented her mother from accomplishing this goal was the fact that no "eligible" suitor "of real consequence" had declared himself during the few weeks Julianna had been in London.

Unfortunately, just before they'd left London to come here, her mother had succeeded in wringing an offer of marriage from Sir Francis Bellhaven, a repulsive, elderly, pompous knight with pallid skin, protruding hazel eyes that seemed to delve down Julianna's bodice, and thick pale lips that never failed to remind her of a dead goldfish. The thought of being bound for an entire evening, let alone the rest of her life, to Sir Francis was unendurable. Obscene. Terrifying.

Not that she was going to have any choice in the matter. If she wanted a real choice, then hiding in here from other potential suitors her mother commandeered was the last thing she ought to be doing. She knew it, but she couldn’t make herself go back to that ball. She didn’t even want a husband. She was already eighteen years old, and she had other plans, other dreams, for her life, but they didn't coincide with her mother's and so they weren't going to matter. Ever. What made it all so much more frustrating was that her mother actually believed she was acting in Julianna's best interests and that she knew what was ultimately best for her.

The moon slid out from behind the clouds, and Julianna stared at the pale liquid in her glass. Her father said a bit of brandy never hurt anyone, that it eased all manner of ailments, improved digestion, and cured low spirits. Juliana hesitated, and then in a burst of rebellion and desperation, she decided to test the latter theory. Lifting the glass, she pinched her nostrils closed, tipped her head back, and took three large swallows. She lowered the glass, shuddering and gasping. And waited. For an explosion of bliss. Seconds passed, then one minute. Nothing. All she felt was a slight weakness in her knees and a weakening of her defenses against the tears of futility brimming in her eyes.

In deference to her shaky limbs, Julianna stepped over to the stone bench and sat down. The bench had obviously been occupied earlier that evening, because there was a half-empty glass of spirits on the end of it and several empty glasses beneath it. After a moment she took another sip of brandy and gazed into the glass, swirling the golden liquid so that it gleamed in the moonlight as she considered her plight.

How she wished her grandmother were still alive! Grandmama would have put a stop to Julianna's mother's mad obsession with arranging a "splendid marriage." She’d have understood Julianna’s aversion to being forced into marriage with anyone. In all the world, her father’s dignified mother was the only person who had ever seemed to understand Julianna. Her grandmother had been her friend, her teacher, her mentor.

At her knee Julianna had learned about the world, about people; there and there alone she was encouraged to think for herself and to say whatever she thought, no matter how absurd or outrageous it might seem. In return, her grandmother had always treated her as an equal, sharing her own unique philosophies about anything and everything, from God's purpose for creating the earth to myths about men and women.

Grandmother Skeffington did not believe marriage was the answer to a woman's dreams, or even that males were more noble or more intelligent than females! "Consider for a moment my own husband as an example," she said with a gruff smile one wintry afternoon just before the Christmas when Julianna was fifteen. "You did not know your grandfather, God rest his soul, but if he had a brain with which to think, I never saw the evidence of it. Like all his forebears, he couldn't tally two figures in his head or write an intelligent sentence, and he had less sense than a suckling babe."

"Really?" Julianna said, amazed and a little appalled by this disrespectful assessment of a deceased man who had been her grandmother’s husband and Julianna's grandsire.

Her grandmother nodded emphatically. "The Skeffington men have all been like that – unimaginative, slothful clods, the entire lot of them."

"But surely you aren't saying Papa is like that," Julianna argued out of loyalty. "He's your only living child."

"I would never describe your papa as a clod," she said without hesitation. "I would describe him as a muttonhead!"

Julianna bit back a horrified giggle at such heresy, but before she could summon an appropriate defense, her grandmother continued: "The Skeffington women, on the other hand, have often displayed streaks of rare intelligence and resourcefulness. Look closely and you will discover that it is generally females who survive on their wits and determination, not males. Men are not superior to women except in brute strength."

When Julianna looked uncertain, her grandmother added smugly, "If you will read that book I gave you last week, you will soon discover that women were not always subservient to men. Why, in ancient times, we had the power and the reverence. We were goddesses and soothsayers and healers, with the secrets of the universe in our minds and the gift of life in our bodies. We chose our mates, not the other way around. Men sought our counsel and worshiped at our feet and envied our powers. Why, we were superior to them in every way. We knew it, and so did they."

"If we were truly the more clever and the more gifted," Julianna said when her grandmother lifted her brows, looking for a reaction to that staggering information, "then how did we lose all that power and respect and let ourselves become subservient to men?"

"They convinced us we needed their brute strength for our protection," she said with a mixture of resentment and disdain. "Then they ‘protected’ us right out of all our privileges and rights. They tricked us."

Julianna found an error in that logic, and her brow furrowed in thought. "If that is so," she said after a moment, "then they couldn't have been quite so dull-witted as you think. They had to be very clever, did they not?"

For a spilt second her grandmother glowered at her, then she cackled with approving laughter. "A good point, my dear, and one that bears considering. I suggest you write that thought down so that you may examine it further. Perhaps you will write a book of your own on how males have perpetrated that fiendish deception upon females over the centuries. I only hope you will not decide to waste your mind and your talents on some ignorant fellow who wants you for that face of yours and tries to convince you that your only value is in breeding his children and looking after his wants. You could make a difference, Julianna. I know you could."

She hesitated, as if deciding something, then said, "That brings us to another matter I have been wishing to discuss with you. This seems like as good a time as will come along."

Grandmother Skeffington got up and walked over to the fireplace on the opposite wall of the cozy little room, her movements slowed by advancing age, her silver hair twisted into a severe coil at her neck. Bracing one hand on the evergreen boughs she'd arranged on the mantel, she bent to stir the coals. "As you know, I have already outlived a husband and one son. I have lived long, and I am fully prepared to end my days on this earth whenever my time arrives. Although I shall not always be here for you, I hope to compensate for that by leaving something behind for you… an inheritance that is for you to spend. It isn't much."

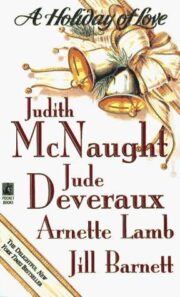

"Miracles" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Miracles". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Miracles" друзьям в соцсетях.