She was about to ask him what he meant when she glanced out of the window and saw that two red orbs, which she had taken for berries, suddenly blinked and moved, and she realised with a shock that they were eyes. She looked to right and left and saw that there were more eyes all round them.

‘Are there wolves here?’ she asked apprehensively.

‘Wolves—and worse,’ he added under his breath.

She sat back in her seat, chastened. Wolves, bears perhaps… She was a long way from Hertfordshire. She was glad of the coach and the safety it offered. It was sturdily built and would withstand an attack by wolves or any other animals which might be lurking close by. She was glad too of the outriders and the pistols they carried—a warning to predators with two legs and a protection against those with four.

She endeavoured to take an interest in the scenery again, but it had lost some of its glamour for, underneath the beauty, danger lurked.

As the coach climbed further the sky began to darken, as if to match her thoughts, turning from blue to indigo. Clouds blew up rapidly and it looked as though it would rain.

‘We are going to have a storm,’ said Elizabeth. ‘Are there any inns nearby where we can stop until it passes?’

‘No, there is nothing for miles, but no matter; in another half hour, or hour at most, we should be there.’

There was a distant rumble and the threatened storm began to make itself felt. The sky was suddenly lit from behind, glowing with a lurid brightness before quickly darkening again. Inside the coach, it was becoming hard to see, and matters were made worse when the trees began to thicken as the road went into a forest of dense trees. They cast long shadows, and Elizabeth could barely make out her husband’s features, although he was sitting only a few feet away from her.

They emerged at last, but it was scarcely any brighter beyond the trees for the sky was now almost black. Another rumble, closer this time, tore the silence and a few minutes later the rain began to pour. The thunder grew louder as the storm broke overhead, and the sky was rent apart by a jagged spike of lightning which ran down to the ground in a network of brilliant veins. The horses neighed wildly, rearing up and flailing their hooves in the air. The carriage rocked from side to side as the coachman tried to hold them, and Elizabeth took hold of the carriage strap which hung from the ceiling. She clung on as she was bounced and jolted this way and that. She managed to keep her seat until the horses at last quieted, but she did not let go, knowing that another flash of lightning would scare the horses again.

‘How much farther?’ she asked.

‘It is not far now,’ said Darcy, holding onto the strap which hung on his side of the carriage.

Another flash of lightning lit the sky and revealed an eerie shape on the horizon, a silhouette of spires and turrets that rose from a rocky pinnacle—a castle, but not like those in England, whose solid bulk sat heavily on the ground. It was a confection, a fragile thing, tall and thin and spindly. And then the sky darkened and it was lost to view.

The rain was coming down in earnest, drumming on the roof of the coach, and Elizabeth was glad when the gatehouse came in sight. The coachman held the horses and guided them over the last stretch of road. There was a pause at the gatehouse, and through the wind and the rain, Elizabeth heard a shouted exchange between the coachman and the gatekeeper. Then the windlass creaked and the drawbridge was lowered, its chains clanking in the rain-sodden air before it settled with a dull thud on the reverberating ground.

The coach traversed the drawbridge and Elizabeth glimpsed a steep drop on either side, and then they were through, into the courtyard. Armed men in billowing cloaks with hats pulled down over their eyes were patrolling with large hounds, more wolf than dog, and their free hands rested on their sword hilts.

‘There is no need to be afraid,’ said Darcy as Elizabeth shrank back against her seat. ‘This is a wild country and my uncle employs soldiers to protect him from roaming bands of villains.’

‘He employs mercenaries, do you mean?’ asked Elizabeth.

‘If you will. Armed men, at any rate, who are in his employ.’

Elizabeth heard the drawbridge being raised behind them, and as it clanked shut on its great chains, she knew a moment of panic, thinking wildly, We’re shut in.

Darcy touched her hand in silent support and the gesture calmed her, and the sight of liveried footmen emerging from the castle dispelled much of her fear. Darcy stepped out of the coach as the footmen unloaded it, and he handed Elizabeth out. The butler appeared, a man past youth but not yet old, with bright eyes that missed nothing as they ran with recognition over Darcy and then ran more watchfully over Elizabeth. He greeted them with a few barely comprehensible words in garbled and heavily accented English, then bowed them towards the steps that led up to the massive oak door. Darcy returned his greeting and then stood aside to allow Elizabeth to precede him through the door.

As she stepped over the threshold, there was a grating sound and one of the axes which was displayed above the door, just inside the hall, came loose of its fastenings and fell to the floor. It missed Darcy by inches and Elizabeth by more than a foot. There was an initial moment of shock, but then they quickly recovered their composure. Not so the butler, however, who cried out in a strange language and rolled his eyes in fear.

It was not an auspicious beginning to their visit. Nor was the walk across the vast, echoing hall, with its dark stone walls and its draught-blown torches and its gloomy wall hangings. But once they were shown into the drawing room things improved. The room was warm with the heat of a log fire, which crackled in an enormous stone fireplace. The carpet was old but not threadbare, and the furniture, though dark and heavy, was of a good quality. Sitting in a chair with his legs stretched out to the fire was a man whom Elizabeth took to be the Count.

The butler announced the Darcys in a foreign tongue and the Count rose, surprised, his look of astonishment quickly giving way to one of welcome. He was somewhat strange of appearance, being unusually tall and very angular, with a finely-boned face, long, delicate fingers, and features which gave him a perpetual look of haughtiness, yet his manner when he greeted Darcy was friendly.

Elizabeth let her eyes roam over the Count’s clothes, which were reassuring in their familiarity, for they were the kind worn by country gentlemen in England. He wore a shabby but well-cut coat of russet broadcloth with a ruffled shirt, which had once been white but was now grey with many washings, beneath which he wore russet knee breeches and darned stockings. His black shoes were polished, but they too were shabby. The only thing she could not have seen on some of her more countrified neighbours was his powdered wig, which would have marked him out as old-fashioned, eccentric even, in Hertfordshire.

The two men spoke in a foreign tongue which Elizabeth did not recognise. It seemed to bear some resemblance to French but many of its words were unfamiliar, and she could not understand what was being said. Darcy quickly realised this and reverted to English. The Count, after a moment of surprise, glanced at Elizabeth and then, understanding, spoke in English too, though he spoke it with a heavy accent and a strange intonation.

‘Darcy, this pleasure, it is not expected,’ he said, ‘but you are welcome here. Your guest, too, she is welcome.’

He extended his hand and the two men shook hands with a firm grip.

‘Thank you,’ said Darcy. ‘I am sorry I could not give you warning, but I did not like to send a messenger on to the castle alone.’

‘The road to the castle, it is not a safe one,’ the Count agreed. ‘But what does it matter? My housekeeper, she is always prepared for guests. And this so charming young woman is…?’ he asked.

‘Elizabeth,’ said Darcy, taking her hand and drawing her forward.

‘Elizabeth,’ said the Count, bowing over her hand. ‘A beautiful name for a most beautiful lady. Elizabeth…?’

‘Elizabeth Darcy. My wife,’ said Darcy with wary pride.

‘Your wife?’ asked the Count, recoiling as though stung.

‘Yes. We were married three weeks ago.’

‘I had not heard,’ said the Count, quickly recovering himself, ‘and that, it is not usual; en général I hear of things which concern the family very quickly. But we are out of the way here…’ he said, looking at Elizabeth curiously before turning his attention back to Darcy. ‘And so, you are married, Fitzwilliam. It is something I thought I would not see.’

‘There is a time for everything,’ said Darcy, ‘and my time is now.’ He completed the introduction, saying, ‘Elizabeth, this is my uncle, Count Polidori.’

Elizabeth dropped a curtsey and said all that was necessary, but she was not entirely at ease. Though the Count was courteous and charming she sensed an undercurrent of curiosity and something else—not hostility exactly, but something that told her he was not pleased about the marriage. She wondered if he too thought that Darcy should have married Anne.

‘The day, it is not a pleasant one for your journey,’ said the Count. ‘Alas, it rains often in the mountains and we have many storms. The darkness, too, it is not agreeable. But no matter, you are here now. My housekeeper, she will show you to your chamber at once. You will want to change your wet clothes, I think. I have already dined, but you must tell me when you would like to eat and my housekeeper, she will prepare a meal—unless you would like better to have something in your room?’

Finding herself suddenly tired, and knowing too that Darcy had something he wished to discuss with the Count, Elizabeth seized on the opportunity to retire to her chamber and said that something on a tray would be welcome.

The Count made her a low bow and rang the bell. It set up a dolorous clanging which echoed from somewhere deep in the bowels of the castle, and Elizabeth wondered how far the housekeeper would have to walk to reach the drawing room. Whilst they waited, the Count continued to ask them about their journey and commiserate with them on the difficulties of such remote travel. The housekeeper arrived at last, a dour woman, small and watchful. She seemingly spoke no English, for the Count addressed her in his own tongue. She inclined her head and then, saying something incomprehensible and yet at the same time so expected that Elizabeth had no difficulty in understanding it, she conducted Elizabeth from the room.

As the door closed behind her, Elizabeth heard Darcy saying to the Count, ‘I must speak to you on a matter of great importance,’ and the Count saying gravely, ‘Yes. I can see it. There is much to discuss.’

What there was to discuss, Elizabeth did not know, but she was beginning to wonder if it had something to do with the marriage settlement. That would explain why Darcy was reluctant to discuss it with her, for he would not want her to feel uncomfortable that her dowry had been so small. Her parents had given up all attempts to save many years before, and what little they had possessed had been used up when they had had to pay Wickham to marry Lydia. Elizabeth knew that Darcy did not care for himself, but for their children… It was customary for the bride’s portion to be settled on the children, and it might well be that Darcy needed the Count’s advice on how to compensate any future offspring for her own lack of funds. It was also possible that that was partly responsible for the coldness of some of Darcy’s family.

She followed the housekeeper across the hall and up a flight of stone steps. They had been worn in the middle where countless feet had trodden over the centuries, and their footsteps echoed with a hollow sound. Then the housekeeper turned along a twisting passageway before going up a spiral staircase and into a turret room.

Annie was already there, unpacking Elizabeth’s things. There was a large four-poster bed in the middle of the room, hung with red velvet drapes, and assorted pieces of heavy furniture arranged around it: a washstand, a wardrobe, a chest of drawers, a writing table, and, pushed under the table, a chair. There was also a dressing table, but it was of a different type to the other furniture, a delicate piece painted in soft blues and pinks, with slender legs tapering into dainty gilded feet. Narrow windows were set vertically into the walls, which were very thick. Beside the window hung heavy velvet drapes which had not yet been drawn. In the grate was a fire. It was as yet a puny thing, having been so recently lit, but the huge logs were starting to kindle, and before long there would be a blaze. Candles were set around the room, showing it to be a perfect circle, and the stone wall above the bed was softened by a tapestry.

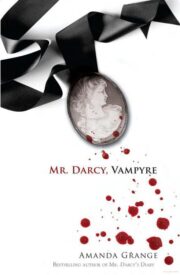

"Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" друзьям в соцсетях.