The housekeeper murmured something unintelligible then curtsied and was about to withdraw when Elizabeth said, ‘One moment.’

The housekeeper stopped, arrested by the tone of her voice.

‘There is no mirror on the dressing-table,’ said Elizabeth, trying to show by a kind of pantomime what she meant. ‘Will you have one sent up please?’

But either the housekeeper did not understand her, or there were no mirrors to be had, for she shook her head emphatically and then withdrew.

‘Well,’ said Annie, ‘folks are strange hereabouts and no mistake. First, all the talk in the servants’ hall, and now this. No mirror indeed! How do they expect a lady to dress without one?’

‘Never mind,’ said Elizabeth, thinking that she would ask the Count on the morrow. ‘She probably did not understand me.’ She removed her cloak then asked curiously, ‘What talk in the servants’ hall?’

‘Nothing but idle nonsense,’ said Annie. ‘Saying as how the axe falling means you’re to cause Mr Darcy’s death. Saying that it fell once before when the Count and his wife walked through the door and look what happened to her. Will you wear the blue dress or the lemon tonight, Ma’am?’

‘Neither,’ said Elizabeth. ‘I will be having something in my room, so there is no need for me to dress for dinner. What do you mean, the axe falling means I will cause Mr Darcy’s death?’

‘Well, Ma’am, they say that as the axe fell when you were both walking through the door, and it fell nearer to him than to you, that means you’re going to kill him or some such nonsense. They were all shaking their heads and muttering about it when I went into the kitchen. Most of them don’t speak a word of English, but Mr Darcy’s valet told me what it was all about. Heathenish nonsense, all of it.’

‘I don’t think they’re heathens,’ said Elizabeth absently. ‘On the contrary, they seem to cross themselves a great deal. As we came to the castle, the local people crossed themselves every time the coach passed.’

‘Even so, Ma’am, they’re not like the people at home.’

‘No, they are not,’ said Elizabeth.

She thought of all her friends and neighbours at home. Their absurdities did not seem so absurd at a distance; instead they felt reassuring. Even the memory of Mr Collins seemed endearing rather than ridiculous.

Annie finished unpacking and then pulled the curtains across the windows. The fire had blazed up and the room was beginning to feel warmer. Elizabeth slipped out of her wet clothes and into a dry woollen dress and then stretched out her hands to the fire. They were very cold, but at last she felt them beginning to thaw.

There was a timid knock at the door and a young maid entered, bearing a tray of something hot and appetising. She stayed as far away from Elizabeth as possible as she crossed the room and put the tray down on the writing table, looking at her with frightened eyes.

‘What did I tell you?’ asked Annie in aggrieved accents as the maid hurried out of the room. ‘She’s one of the day servants. They’re the worst. They won’t even stay in the castle overnight; they say they see things, unnatural things.’

Elizabeth walked over to the tray and looked down at the stew.

‘It tastes better than it looks,’ Annie said. ‘I had some in the kitchen.’

Elizabeth picked up the spoon that was set beside the bowl and tasted the dish, which was a kind of chicken stew with a distinctive flavour.

‘Peppers, those are the things they put in it to make it taste like that,’ said Annie. ‘Better than all that garlic in Paris, this doesn’t taste so bad.’

Elizabeth broke off a piece of bread and ate it with the stew. When she had finished, Annie removed the tray and Elizabeth, left alone, wandered round the room. She examined the few books that were placed on a bookcase by the window and gazed at the tapestries, but instead of soothing her before she went to sleep, the contents of the room unsettled her. The books were not like those in the Longbourn library, smelling richly of leather; they were damp and they smelt of mould.

The tapestry too was unsettling. It displayed a bold picture worked in faded reds and emeralds and golds, and it appeared to be some kind of bestiary. It showed a forest populated with strange creatures: wolves of gigantic proportions, their sharp faces dominated by red, glowing eyes; bats with human faces, monstrous in size; satyrs and dragons and basilisks; and in one small corner, a wan-faced woman with flowers in her hair. The monsters reminded her of the pictures in the books of fairy tales she had read as a child. In the safety of Longbourn, they had seemed ridiculous, but here, in the castle, they did not seem so easy to dismiss. The idea of Little Red Riding Hood losing her way in the woods close at hand did not seem an impossibility; nor the idea of the Sleeping Beauty being haunted by a malevolent witch who caused her to sleep in the mouldering castle for a hundred years; nor of men who were beasts and of beasts who were men.

Her one satisfaction was that the tapestry was hung above the bed, so that she would not have to look at it as she lay down to sleep.

She wandered over to her travelling writing desk, which Annie had unpacked, and took out her writing implements. Then she sat down to finish her letter to Jane. She read through what she had written so far, ending with: Darcy respects his uncle and wants to seek his advice, about what I am not quite sure. I only hope it sets his mind at rest and leaves him free to follow his heart which I know, Jane, leads to me.

I must go now, but I will write to you again when we reach the castle. For the moment, adieu.

She then continued:

We have arrived at the castle and it is as remote a place as I ever hope to visit. It is also the strangest and I feel very alone. I wish you were here, Jane. I miss your calm sweet temper and your goodness and ability to see the best in everyone. Everything here is strange. We arrived at the castle in a terrible storm. It is in a far-flung part of the mountains and surrounded by woods which are inhabited by wolves. I saw them on the way here, running alongside the coach, their fur grey and their eyes shining red through the foliage. I can hear them howling at the moon as I write. The castle itself is an old building built of stone, dark and gloomy, and it is in a state of disrepair. When we arrived, one of the axes fell off the wall, narrowly missing Darcy and myself. The servants say it means I will cause his death! And yet, although I know it is ridiculous, I can’t help feeling afraid. I feel shut in here; indeed, when the drawbridge was raised behind me I felt like a prisoner. Things would not seem half so bad if you were by my side. Together we would laugh at the wolves and the strange portents. But without you, my own dearest Jane, I find myself surprisingly nervous. God forbid I should end up like Mama! Write to me soon and laugh me out of my idiocy. Without any letters from home I feel strangely alone. Tell me of our Aunt and Uncle Gardiner, and the dear children. Remind me that there is a world beyond this one and that order and familiarity and calm and security exist. Tell me too of the delights of London and your beloved Bingley. I hope your fears are less and your joys greater than mine.

Oh, I wish you were here! I need my Jane to talk to, and not just about the castle. I need to talk to you about my marriage, too. Darcy has not come to me again, though the hour is late. I find I am no longer surprised by his absence. Indeed, I find now that I would be surprised if he joined me. This cannot be a good thing. But perhaps I am only thinking this way because I am tired. It has been a long and curious day. I will get some rest. I am sure things will seem better in the morning.

She sanded her letter and put it away, then, snuffing all but one of the candles, she climbed into bed. She arranged the coverlet and extinguished the final candle, then lay down. Sleep came quickly, but it was not a restful sleep, for it was plagued by disturbing dreams.

Chapter 6

Elizabeth was glad to rise the following morning. She had spent the night running through the forest pursued by wolves, or losing herself in the castle, or being tormented by other unsettling nightmares, and she was pleased to put them behind her.

She dressed warmly, wrapping her thick shawl around her, and left her room. She found her way down from the turret easily, but then she stood hesitating on the landing, uncertain which way to go. Luckily one of the Count’s footmen happened to pass by. He looked at her fearfully, but she did not let him depart before she had made him understand that she wanted to eat and he led her to the dining room. Darcy was already there at breakfast. He rose with a smile on his face and she was instantly calmed. Here was reality. Here was sanity and repose—not in sleep, but in the waking world.

‘Has the Count already eaten?’ she asked, as she was served with a kind of thick porridge which looked unappetising but tasted surprisingly good.

‘Yes, he was up before daybreak. He has gone to consult with some of his friends and neighbours on the matter which has been troubling me. They are scattered over thirty miles or so of hard riding terrain, and he will not be back until tonight.’

‘Has he been able to give you any advice?’

‘Not yet, but I hope that an answer will soon be found.’

She waited for the servants to leave the room and then said, ‘I asked you once before if you regretted our marriage and you said you did not. I need to ask you again.’ She paused, uncertain how to continue. She wanted to say to him, Why don’t you come to me at night? But now that the moment had come, she felt tongue-tied and did not know how to broach the subject.

‘No, of course not,’ he said with a frown. ‘You have no need to ask me and I am only sorry I have made you feel that way.’

‘Are the problems anything to do with the marriage settlement?’ she asked. ‘Is that why you need your uncle’s advice?’

‘Not precisely, no,’ he said evasively. ‘But matters will soon be cleared up, I hope, and then we can forget it and enjoy the rest of our wedding tour.’

He took her hand and kissed it, and she felt heat radiating out from the place where his lips had touched.

A shaft of sunlight came in through the window and Elizabeth, having finished her porridge, said, ‘Let us go out into the courtyard,’ for she glimpsed a small garden, of sorts, through the window and longed to be out of doors.

‘By all means,’ he said.

The rain had abated, but despite the gleam of sunshine, the morning was sulky and promised more rain to come.

The garden itself must once have been attractive, but it was now overgrown. It was square in shape, backed by the grey stone walls of the castle, and in its centre was a stagnant pool, choked with weeds. Little light entered the courtyard and even that was sickly and pale, as if the effort to find its way down into the courtyard had depleted it of energy. Weeds sprouted between the paving stones and yellow grasses competed for space with unhealthy looking ferns. A statue of a satyr rose from the tangle of creeping plants which stalked the ground, but it was broken, its pan pipes lying beside it, coated with moss and lichen.

‘What a pity it is so overgrown,’ she said. ‘It is protected from the wind, and it might be pleasant to walk here if the garden were cleared.’

‘The castle is old and the upkeep is expensive,’ said Darcy, offering her his arm. ‘My uncle doesn’t have enough money to attend to everything that needs doing here. His fortunes have suffered a reverse of late and he has had to let some parts of the castle fall into disrepair.’ He glanced at her as they began to stroll through the garden. ‘I suppose I do not notice its deficiencies because I am used to them. I have loved the place since I was a boy. But you, I think, do not.’

‘No, I must confess I don’t,’ she said. ‘It seems very forbidding to me, and it is not just the castle. The language is strange, the gossip…’

‘It is not like you to listen to gossip,’ he said.

‘No, I know, but I feel different here, not like myself. I feel shut in, trapped.’ She shuddered as she remembered the drawbridge clanging shut and she pulled her shawl more tightly about her. ‘When the drawbridge was raised behind me, I felt as if I were a prisoner.’

‘The drawbridge is to keep people out, not keep them in,’ he said, putting his hand over her arm reassuringly. ‘We are in a very remote part of the country and there are lots of bandits hereabouts. They would willingly prey on the castle if its defences weren’t secure.’

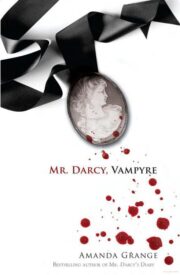

"Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" друзьям в соцсетях.