‘Elizabeth!’ he said again, as he began to climb the stairs towards her place on the half landing.

Illuminated by the light from the large window she made a lovely sight. Her cheeks were aglow, her eyes sparkled, and she radiated good humour and health.

‘I am glad you enjoyed the company of my uncle’s guests, but it would be well not to encourage them too far,’ he said in some agitation.

‘I don’t know what you mean,’ she said in surprise.

‘You were enjoying their attentions,’ he said with a sudden spurt of jealousy.

She was taken aback by the injustice of his remark and flashed back, ‘And why should I not? I never get yours.’

He looked startled.

‘What do you mean?’ he asked.

‘You know full well what I mean. We have been married for weeks and yet I am still not your wife.’

‘Elizabeth—’ he said, and then stopped, as if at a loss.

‘Why do you never come to me?’ she asked him, hurt.

‘I—’ He shook his head. ‘I should never have brought you here,’ he said.

‘Then why did you?’ she asked.

‘I didn’t know how it would be. I thought it would be different.’

‘Different? How?’

‘Not so difficult—or yes, difficult, but difficult in different ways.’

‘I don’t see what is so difficult,’ she said, looking at him beseechingly and reaching out a hand to touch him.

‘No, I know you don’t,’ he said, but he did not take her hand.

‘Then explain it to me. Talk to me, Darcy,’ she begged him, taking his hands and looking into his eyes. ‘Tell me what is wrong. I will not leave this spot until you talk to me, though sunset is already on its way. I will stand here until dark if necessary.’

He lifted his eyes but he did not look at her, he looked beyond her, over her shoulder, to the reddening sky. Then his whole attitude changed.

‘That’s no sunset,’ he said.

She was startled and, looking over her shoulder, she saw that he was right. The sky was not flamed with crimson, it was stained with a fire’s glow.

A bell on the stables started to ring out and there was a clamour from the courtyard outside. Through the window she saw the mercenaries mount with all speed as the grating of the drawbridge’s chains rent the air. The vast bridge began to lower and the mercenaries streamed across it, filling the air with the flash of their bright swords.

‘There is no time to lose,’ said Darcy, seizing Elizabeth by the hand and pulling her down the stairs, just as the Count appeared at their foot.

‘Quickly,’ the Count said, ‘you must go at once. The mob, it is on the move.’

Elizabeth was at once alarmed, remembering everything she had heard about the revolution in France, when the mobs had stormed the houses of the nobility and wreaked havoc, burning and murdering as they went.

‘We can’t leave the castle,’ she said. ‘The walls are thick. We will be safe here.’

‘We can and we must leave,’ said Darcy.

The Count said something under his breath and Elizabeth thought he said, Get her away from here. It is her they will not stand for, before realising that she must be mistaken, because those words didn’t make sense. Then, in a louder voice, he said, ‘Do not stop for your things. Me, I will have them sent on.’

‘We can’t leave at night,’ said Elizabeth. ‘The horses—’

‘We cannot ride our own horses, there is no time to have them readied,’ said Darcy.

‘You will find everything needful at the usual place,’ said the Count to Darcy. ‘Go quickly, my friend, and the wind, may he be at your back.’

Darcy nodded, then saying, ‘Send our things on,’ he turned to Elizabeth and said, ‘We must go.’

Caught up in the sense of urgency, she ran down the flight of stairs with Darcy beside her, but when she headed for the door he caught her hand and, pulling her along with him, took her to another staircase leading down into the bowels of the castle. The steps were smooth and slippery, and the cold bit into Elizabeth’s feet through the soles of her shoes. The light faded as the windows receded and they were running in near darkness, until at last Darcy pulled her through a studded door. There he took a torch from a sconce on the wall and fumbled on a shelf, striking a light with a tinder box. The torch caught fire and a light shone out, a dreadful echo of the torches of the mob.

They were in a storeroom with sacks of flour stacked against the walls. It was hewn out of the rock on which the castle stood, and the ceiling was so low that Darcy had to stoop and Elizabeth was in danger of hitting her head.

Darcy pulled aside the heavy sacks of floor and then, taking the torch in one hand and Elizabeth’s hand in the other, he led her on through the door that had been revealed. Elizabeth found herself in a dark, dank tunnel with water running down the walls, and she shuddered with cold and fear. The floor was uneven, and twice she stumbled, but she quickly righted herself, wondering where they were going. She guessed they were passing beneath the castle walls and the thought of so much weight above oppressed her so that she hurried her pace. At last they came to another thick door which was barred with a stout oak log. Darcy again handed her the torch and then heaved the bar out of its housings and opened the door. Beyond was a tangled thicket of thorns and ivy, disguising the opening, and beyond that lay the forest.

A wolf howled and Elizabeth’s pulse jumped at the thought of the dangers ahead and the dangers behind.

Darcy extinguished the torch and threw it aside. Then he led her cautiously ahead, pushing the creepers out of the way with his hands and making a passage for her through the thick and thorny tangle. Even so, she scratched her face and caught her cloak on a briar before she was able to stand upright in a dense part of the forest.

Through a gap in the canopy above there came the faint and sickly light of a new moon rising in the sky, floating like a ghost in the stark and terrible blackness. Beneath it was an angry red glow, moving towards the castle. But the castle was now some way behind them and Elizabeth stopped to catch her breath.

‘No, we can’t stop yet,’ Darcy said. ‘We are still not safe.’

There were far-off shouts and the dim commotion of steel on steel, but closer to hand all was quiet.

Darcy turned and looked ahead. Through the thick and gnarly tree trunks a cottage could be glimpsed, and it was to this building that Darcy headed, Elizabeth at his side. They moved quickly and quietly, their breath misting in the air and their lungs gasping with the cold.

They had almost gained the cottage when a shadow detached itself from the surrounding blackness and Elizabeth froze. She could not at first see what it was, it seemed too large for a wolf or a man, but then it split and separated and she could see that it was made up of half a dozen men or more, each holding a club.

‘They were waiting for us,’ said Darcy under his breath. ‘We were betrayed.’

He began to back away from the men, pushing Elizabeth behind him, protecting her with his body. And then she heard a twig crack behind her and she froze. Her arm was seized and she was pulled backwards, amidst a flurry of blows and cries. And then from out of nowhere, a wind arose, circling with force and speed, and she felt a roaring in her ears. She could see nothing and hear nothing, save a confused jumble of sounds and images, and then suddenly everything went quiet. The wind dropped, the cries died, and she was standing alone in the forest. There were no hands holding on to her, no one anywhere. The forest was empty.

‘Darcy!’ she called, softly to begin with in case there were any enemies nearby. But then, needing to hear a friendly voice whatever the cost, she called more loudly, ‘Darcy!’

‘It’s all right,’ he said, ‘I’m here.’

Somehow he was right beside her, though she had not seen him or heard him a moment before.

‘What happened?’ she asked.

‘Some of the mob knew what we would do and tried to cut us off,’ he said.

‘I know, but after that. The wind, the cries, what happened to the men?’

‘Gone,’ he said.

He turned slightly and the moonlight fell on one side of his face. His hair was dishevelled and his clothes were awry, and she saw to her horror that he had blood on his mouth.

‘You’re hurt,’ she said, removing her glove and lifting her hand to see to his wound.

He caught it, stopping her, and all of a sudden they were not in the forest, they were nowhere, in some strange realm where only they two existed, and where every inch of her needed him. She looked into his eyes and something shot between them, connecting them, joining them, making them one. She felt the hunger in him, she saw the longing in his eyes and her heart stopped beating. Then he wrenched himself away.

‘What is it?’ she begged him. ‘What’s wrong? Why won’t you tell me?’

‘I should never have let her do this to me,’ he muttered under his breath, ‘but then, if I hadn’t, I would never have met you.’

There was a low murmur like the sea coming towards them and the red glow was getting closer.

‘We must go,’ he said.

He took her hand again and together they ran through the forest, snaking through the tree trunks and jumping over gnarled roots until they came to the cottage door.

Darcy knocked swiftly and quietly in a distinctive tattoo. The door was opened at once by a woman carrying a candle, which gave out only the smallest light. She said something to Darcy in a foreign tongue and he thanked her, then took Elizabeth through the house and out of the door at the other side. A barn lay ahead, and a man was leading a couple of horses, both saddled and ready to go.

Elizabeth looked at her horse with some apprehension. It was no gentle mount, but a large and restive looking creature, and it had a man’s saddle on its back. There was no help for it, she had to mount. Darcy lifted her into the saddle, then mounted his own animal, and they set off. She could barely hold the horse, but she hoped it would become less restive when it had run off some of its energy.

‘Where are we going?’ she asked.

‘Across the mountains,’ he said.

‘But the Count—’ she said.

‘—Will survive,’ he said. ‘He has survived worse.’

His horse shot forwards and Elizabeth’s animal followed, and they were swallowed up by the dark.

Chapter 8

The night was long and wearisome. The horses were strong and not used to their riders, so that Elizabeth could only hold her mount with difficulty. The saddle was uncomfortable, and it was not long before her arms and legs were aching with the unaccustomed exertion. At last her horse began to tire and she was able to relax a little, which came as some relief, but the road seemed endless and she longed for journey’s end.

To begin with they rode side by side but, as the road narrowed, Darcy began to ride ahead of her, stopping at each junction to consider the way.

‘Haven’t you been here before?’ she asked him.

‘Yes, I have, but not for some time,’ he said, looking down three roads. ‘This way I think.’

‘You think?’ she asked in a dispirited voice.

He looked at her with sympathy.

‘Tired?’ he asked in concern.

She sat up in the saddle.

‘No,’ she lied, ‘I have never felt better.’

He smiled at her blatant but courageous lie and there was admiration in his eyes, then he laughed, and she laughed too. It was a bright sound in the deserted forest, ringing through the trees, and it heartened them, until it was answered by the desolate howling of a wolf, and then their laughter died.

Darcy turned to the right and Elizabeth followed him.

The road now began to wind downwards until it reached a hollow, where ice was already starting to form on the shallow pools of water which had collected there, but once through the hollow, it began to climb steadily. The horses had to pick their way carefully as the road began to narrow and finally dwindled into a path.

The branches of the trees closed in on them from every side, and when the path became a track, the trees were so close that the branches reached out and groped at Elizabeth as she passed, snagging her cloak and tangling in her horse’s mane. The animal whickered nervously and began to roll its eyes. For all its fatigue, it became jittery and tried to turn back, and Elizabeth had to struggle to keep it moving onwards, threading its way through a tangle of tree trunks and wading through deep undergrowth whilst she swerved and ducked to avoid the low hanging branches.

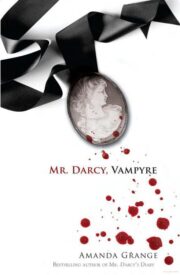

"Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" друзьям в соцсетях.