I didn’t dream it, she thought, with a terrifying realisation. I was in the past. I was there.

She dropped the book, letting it fall from numb fingers. Despite its great antiquity and obvious value, she felt only the vaguest sense of relief when it was caught by other hands which stopped it plummeting to the floor, for one of the Prince’s guests had entered the room and had saved it from its fall.

‘My dear young lady,’ he said in concern, ‘you are as white as a ghost. Are you unwell?’

She turned towards him and had difficulty in making out his face. It seemed ageless: unlined and yet old, sympathetic and yet devilish. It floated before her in silent mockery, completely at odds with his words and behaviour, and she felt very strange.

‘Here,’ he said, offering her his arm.

She did not respond, only looking at him, and he pulled her hand through his arm himself, saying, ‘Let me escort you to a seat.’

As he touched her, she felt her will altering, flowing, and merging with his. She moved with him to one of the window seats. She was ensorcelled by him. Her body was light and ethereal and her thoughts were unclear, as though her mind was filled with mist.

She was aware of a peculiar sensation as the room around her began to alter, distorting and changing like a wet portrait in the rain. The green wallpaper began to melt and run down the walls and a deep ochre ran down in great rivulets behind it and took its place. The curtains too began to change, their dark green velvet dropping away to be washed over with rivers of gold silk. Pictures were appearing and mirrors disappearing; beneath them the console tables were altering, their legs narrowing and their tops flowing with marble; the vases of flowers were being replaced with porcelain and ormolu clocks. The carpet was giving way to polished floorboards and the sound of unearthly laughter filled the air. He seized her in his arms and waltzed with her around the room, whispering to her in some unintelligible language.

‘I am not well,’ said Elizabeth, her heart beating strangely and her mind trying to hold on to reality.

‘No?’ he asked. ‘I think you are very well.’

Strange faces peered at her as the room was suddenly full of people, laughing and chattering and looking at her through their masks.

She put her hand to her head, feeling it throb, and then, through the mist, she heard something familiar. It was Darcy’s voice.

The gentleman was saying to him, ‘It is nothing, never fear, the lady is feeling unwell that is all, but I am caring for her. Please do not let us detain you.’

‘No,’ she wanted to say. ‘I don’t want you to care for me, I want to be with my husband.’

But nothing came out.

She turned beseeching eyes to Darcy and she saw him as if from a great distance, through a distorting glass, but his words were firm and clear.

‘She has no taste for your company,’ he said.

‘No?’ said the gentleman. ‘But I have a taste for her.’

Hers, thought Elizabeth. He should have said hers.

‘Let her go,’ said Darcy warningly.

‘Why should I?’ asked the gentleman.

‘Because she is mine,’ said Darcy.

The gentleman turned his full attention towards Darcy and Elizabeth followed his eyes.

And then she saw something that made her heart thump against her rib cage and her mind collapse as she witnessed something so shocking and so terrifying that the ground came up to meet her as everything went black.

When she came to, she was in her bed and her maid was sponging her brow with cool, scented water.

‘What happened? Where am I?’ asked Elizabeth, looking round the room and finding it unfamiliar.

‘You’re safe, Ma’am. You’re in your own room in the Prince’s villa. You fainted, that’s all,’ said Annie.

‘But I never faint,’ said Elizabeth, struggling to sit up.

‘Lie back,’ said Annie, putting gentle pressure on her shoulder.

Elizabeth, seeing the room beginning to spin, had no choice but to comply. As she lay back, she realised that she was still in her gown but that her stays had been loosened so that they did not constrict her breathing. She tried to recall exactly what had happened. She had been playing croquet, there had been a storm, she had gone into the library, and then… she could remember no more.

‘It was the weather,’ said Annie. ‘When the clouds blew up it turned sultry. It’s a wonder more people haven’t fainted.’

‘Yes, I suppose so,’ said Elizabeth. ‘Only I’m sure there was something…’

She struggled to catch the elusive memory, but it had gone.

She waited until she felt her strength returning and then she tried to sit up again, this time with more success. Although the room had stopped spinning, she still found it hard to catch her breath and a glance out of the window showed her why. The sky was black and low, trapping the heat like a blanket. The landscape looked strange beneath the dark sky, the colours transformed and the light unnatural.

Annie was still mopping her forehead, but the water, cool to begin with, was now unpleasantly warm, and Elizabeth pushed her hand irritably away.

‘I’ll fetch some fresh water,’ said Annie.

As the door closed behind her, Elizabeth sat up and swung her legs over the edge of the bed. After sitting thus for a few minutes and discovering that she no longer felt faint she got up and walked about the room. She was restless, unable to settle to anything, and when the door opened she was about to send Annie away when she saw that it was not Annie standing there, it was Darcy, with a look of torment on his face.

She held out her hand to him, hoping for the comfort and reassurance of his touch, but he did not respond to her gesture and he made no move to enter the room. Instead he stood by the door, watching her.

‘You don’t remember, do you?’ he asked.

‘Remember what?’ she said, ceasing her restless pacing.

‘You don’t remember what happened.’

‘No,’ she said, ‘but Annie told me. I fainted. It was the heat, she said.’

‘The heat.’

His voice sounded strange and Elizabeth felt a long way away from him, although they were separated by no more than ten or twelve feet. All the difficult and disturbing incidents of the past few weeks, together with the distance from home and her estrangement from Darcy—for she could no longer pretend that they were not estranged—together with the agitation and tears which these things occasioned, threatened to overset her again. She dropped her hand and sank down on the edge of the bed.

She had told herself it was only a matter of time before things were well between them. She had made excuses and invented countless reasons for his absence from her room, but she could deceive herself no longer. He simply did not want her. He had mistaken his feelings and now they must face the consequences.

‘Are you still feeling unwell?’ he asked, looking at her with concern.

‘Yes.’

‘Elizabeth, it was an unpleasant morning, but—’

‘It is nothing to do with the morning,’ she said. ‘It is us. We should never have married.’

He looked stunned.

‘I have been trying to pretend to myself that it was just the newness of our life together, or that you were being considerate, or that it would not be long before you came to me, but I cannot go on pretending. I know now we should never have married. I will not stay here to embarrass you and distress myself.’ She thought of Longbourn and a wave of homesickness washed over her. She wanted to be amongst familiar sights and familiar people. ‘As soon as I feel well enough, I will pack my bags and go back to England.’

‘No! You cannot go! I forbid it!’ he said, striding into the room but then hesitating and stopping before he reached her, with lines of pain etched clearly across his face.

‘There is nothing else to be done,’ she said. ‘This is not a marriage. I am not your wife.’

His complexion became pale and she saw some great emotion wash over him as he struggled for composure, but composure would not come and at last he said in agitation, ‘I can’t come to you. There are things about me you don’t know…’

‘Then tell me!’ she cried, jumping up. ‘That is what men and women do when they are in love. They talk to each other. They share their thoughts and feelings. They share their problems. They share their secrets, they share everything.’ She stopped and sighed, making an effort to master her overwhelming emotion, and then she continued in a calmer manner. ‘Will you not tell me what is worrying you? We are married, Darcy. We took an oath to love each other for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness, and in health. Those words mean something. They mean that we stand together in times of trial and we share our burdens as well as our joys. There is nothing so terrible that we cannot face it if we do so together.’

His face was ashen.

‘I can’t share this with you,’ he said.

‘Why not? Don’t you trust me?’ she asked.

‘It’s not that—’

‘Then what is it?’ she cried.

He shook his head as though he were being goaded beyond endurance and said, ‘It is for your own good.’

‘How can it be for my own good?’ she cried in astonishment. ‘Whatever your secret, it cannot be more terrible than the pain I am feeling at this moment.’

He started, but then he let out a cry and he said, ‘If I tell you, then there will no going back. Once you have the knowledge you will never be rid of it, and if you decide you were happier without it, it will be too late.’

‘Then if you won’t tell me, there is no hope for us,’ she said with a droop of her shoulders.

‘Don’t say that.’

‘What else is there to be said?’

She saw his expression change slightly and she thought that he was weakening. She held out her hand to him and he moved as if he was going to take it. His fingers reached out to her but then he drew them back.

‘No! I can’t. But I can’t go on like this either,’ he said in agony. ‘I have to think.’

He sprang towards the door.

She had a sudden and terrible fear that if she let him leave the room she would never see him again.

‘Darcy!’ she called, but it was too late, for he had already gone.

Chapter 12

Annie soon returned with a bowl of fresh water and sponged Elizabeth’s brow. Elizabeth felt nothing except the emptiness of her own heart. When Annie had finished sponging her brow, Elizabeth got up and went over to her writing desk and finished her letter to Jane.

I can conceal from you no longer the true state of affairs, for I can no longer conceal them from myself. My husband does not love me. I have fought against it but I can deny it no longer. I never thought, when I married my beloved Darcy, that I would return home a few months after my wedding, alone, but I can see no other choice. I cannot live with him and be with him when he constantly rejects me. I don’t know what I will tell Papa, and with Mama it will be even worse. I believe that being the mistress of Pemberley is my only claim to her affection, and without it, I fear she will not welcome me home. I dread her constant admonishments, but with you, dear Jane, I know there will be solace. I shall visit you at Netherfield everyday. Or, at least, not everyday, I shall give you and Bingley some time alone. How wonderful it must be to be loved by your husband! Write to me, Jane, I have not had a letter since leaving England, and although it might not find me as I travel home, what bliss if it does. To hear the sound of your voice, even in a letter, will be a comfort to me. And I need comfort, I fear. How am I to live without him? And will I even be allowed to try? It is scandalous for a married woman to leave her husband, and yet to live with him is beyond my strength. I am in need of love and comfort and sound advice and I am longing to be at home, where you and my Aunt Gardiner will help me.

Your loving sister,

Elizabeth

When she had finished the letter, she handed it to Annie, saying, ‘Give it to one of the footmen at once, I want to make sure it goes to the post today.’

‘Very good,’ said Annie.

Elizabeth looked out of the window and saw that the weather had improved. The sky had lightened and the storm had blown over. From the window came a fresh breeze, luring her out of doors. There was a collection of people by the door, laughing and talking, but further along the house, by the French window leading out of the morning room, there was no one. Being disinclined for company, she decided to make her way out of the villa through this route.

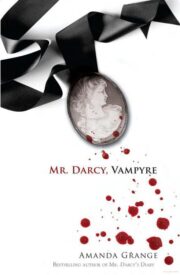

"Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mr. Darcy, Vampyre" друзьям в соцсетях.