Mary was silenced.

‘When I marry, I will have a satin underskirt and a gauze overskirt,’ said Kitty,‘and I will not run off with my husband and live with him in London first.’

‘Kitty, be quiet,’ said Mrs Bennet. She turned to Bingley with a smile. ‘What will you wear, Mr Bingley? A blue coat or a black one? Wickham was married in his blue coat. My dear Wickham!’ she said with a sigh. ‘Such a handsome man. But not nearly as handsome as you.’

I caught Bingley’s eye. It was probable that, if Wickham had had five thousand a year, he would have been allowed to be as handsome as Bingley.

‘I will wear whatever Jane wishes,’ he said.

Where was Elizabeth? I felt my impatience growing.

At last she returned to the room and smiled. All was well.

The evening passed quietly. I received a cold nod from Mrs Bennet when I left, and I wondered what her reception of me would be on the morrow. I saw lines of strain around Elizabeth’s mouth, and I knew she was not looking forward to her interview with her mother.

‘By this time tomorrow it will be done,’ I said.

She nodded, then Bingley and I departed.

‘Her father gave his consent?’ asked Bingley, as we returned to Netherfield.

‘He did.’

‘Jane and I have already set a date for our wedding. We were wondering what you and Elizabeth would think of a double wedding?’

I was much struck by the idea.

‘I like it. If Elizabeth is agreeable, then that is what we will do.’

Bingley and I were at Longbourn early this morning.

‘Mr Bingley,’ said Mrs Bennet, fidgeting as she welcomed him. She turned to me, and I felt Elizabeth grow tense. But her mother merely looked at me in awe and said: ‘Mr Darcy.’

There was no coldness in her tone. Indeed she seemed stunned. I made her a bow and went to sit beside Elizabeth.

The morning passed off well. Mrs Bennet took the younger girls upstairs with her on some pretext, and Elizabeth and I were free to talk. When luncheon was served, Mrs Bennet sat on one side of me, and Elizabeth on the other.

‘Some hollandaise sauce, Mr Darcy?’ said Mrs Bennet.

‘I believe you like sauces.’

I cast my eyes over the table, and saw no less than six sauce-boats. I was about to refuse the hollandaise sauce when I caught sight of Elizabeth’s mortified expression and I determined to repay Mrs Bennet’s new civility with a civility of my own.

‘Thank you.’

I took some hollandaise sauce.

‘And béarnaise? I had it made specially.’

I hesitated, but then put a spot of béarnaise sauce next to the hollandaise sauce.

‘And some port-wine sauce?’ she said. ‘I hope you will take a little. Cook made it specially.’

I took some port-wine sauce and looked at my plate in dismay. I caught Elizabeth’s eye and saw her laughing.

I took some béchamel sauce, mustard sauce and a cream sauce as well, and then set about eating my strange meal.

‘You are enjoying your luncheon?’ asked Mrs Bennet solicitously.

‘Yes, thank you.’

‘It is not what you are used to, I suppose.’

I could honestly say that it was not.

‘You have two or three French cooks, I suppose?’

‘No, I have only the one cook, and she is English.’

‘She is your cook at Pemberley?’

‘Yes, she is.’

‘Pemberley,’ said Mrs Bennet. ‘How grand it sounds. I am glad Lizzy refused Mr Collins, for a parsonage is nothing to Pemberley. I expect the chimney piece will be even bigger than the one at Rosings. How much did it cost, Mr Darcy?’

‘I am not sure.’

‘Very likely a thousand pounds or more.’

‘It must be difficult to maintain,’ said Mr Bennet. ‘Even at Longbourn, it is difficult to keep up with all the repairs.’

We fell into a discussion about our estates, and I found Mr Bennet to be a sensible man. He might be negligent where his family are concerned, but his duties in other areas are carried out responsibly.

I have to forgive him the former negligence as it produced Elizabeth. Her liveliness and vitality would have been crushed under an ordinary upbringing.

I have decided that Georgiana must have a spell without a governess or a companion, so that she might develop her own spirit. I am sure that Elizabeth will agree.

Elizabeth began to ask me how I had fallen in love with her.

‘How could you begin?’ she asked. ‘I can comprehend your going on charmingly, when you had once made a beginning; but what could set you off in the first place?’

I thought. What was it that had started me falling in love with her? Was it when she had looked at me satirically at the assembly? Or when she had walked through the mud to see Jane? Or when she had neglected to flatter me, not telling me how well I wrote? Or when she had refused to try and attract my attention?

‘I cannot fix on the hour, or the spot, or the look, or the words, which laid the foundation. It is too long ago.

I was in the middle before I knew I had begun.’

She teased me, saying I had resisted her beauty, and therefore I must have fallen in love with her impertinence.

‘To be sure, you know no actual good of me – but nobody thinks of that when they fall in love.’

‘Was there no good in your affectionate behaviour to Jane, while she was ill at Netherfield?’

‘Dearest Jane! Who could have done less for her? But make a virtue of it by all means. My good qualities are under your protection, and you are to exaggerate them as much as possible.’

‘You do not easily take offence. It cannot have been easy for you to be at Netherfield – you were not made very welcome – and yet you were amused rather than otherwise by our rudeness.’

‘I like to laugh,’ she admitted.

‘And you are loyal to your friends. You berated me over my treatment of Wickham –’

‘Do not speak of him!’ she begged me. ‘I can hardly bear to think about it.’

‘But I can. He is a loathsome individual, but you did not know that at the time, and you defended him. There are not many women who would defend a poor friend against a rich and eligible bachelor.’

‘However undeserving the “friend” might be,’ she said ruefully.

‘And you were not afraid to change your mind when you learnt the truth. You did not cling to your prejudices, regarding either Wickham or myself. You admitted the justice of what I said.’

‘Yes, I acknowledged that a man who does not give a living to a wastrel is not a brute. That is a sign of great goodness, indeed!’

‘You did everything in your power to help Lydia, even though you knew her to be thoughtless and wild,’ I pointed out.

‘She is my sister. I could hardly abandon her to a rogue,’ she replied.

‘But I am allowed to exaggerate your good points,’ I reminded her. ‘You said so yourself.’

She laughed.

‘Poor Lydia. I thought she had ruined my chance of happiness with you for ever. I could not imagine you would want to be connected to a family in which one of the girls had eloped, especially not as she had eloped with your greatest enemy.’

‘I never thought of that. You had taught me by then that such things do not matter.’

‘I had taught you more than I realized, then. When you came to Longbourn, after Lydia’s marriage –’

‘Yes?’

‘You said so little. I thought you did not care about me.’

‘Because you were grave and silent, and gave me no encouragement.’

‘I was embarrassed,’ she said.

‘And so was I.’

‘Tell me, why did you come to Netherfield? Was it merely so that you could ride to Longbourn and be embarrassed? Or had you intended any more serious consequence?’

‘My real purpose was to see you, and to judge, if I could, whether I might ever hope to make you love me.

My avowed one, or what I avowed to myself, was to see whether your sister were still partial to Bingley, and if she were, to make the confession to him which I have since made.’

‘Shall you ever have courage to announce to Lady Catherine, what is to befall her?’

‘I am more likely to want time than courage, Elizabeth. But it ought to be done, and if you will give me a sheet of paper, it shall be done directly.’

Whilst I composed my letter to Lady Catherine, Elizabeth composed a letter to her aunt and uncle in Gracechurch Street. Hers was easier to write than mine, because it would give pleasure, whereas mine would give distress. But it had to be done.

Lady Catherine,

I am sure you will want to wish me happy. I have asked Miss Elizabeth Bennet to marry me, and she has done me the great honour of saying yes.

Your nephew,

Fitzwilliam Darcy

‘And now I will write a far pleasanter letter,’ I said.

I took another sheet of paper and wrote to Georgiana.

My dear sister,

I know you will be delighted to hear that Elizabeth and I are to marry. I will tell you everything when I see you next.

Your loving brother,

Fitzwilliam

It was short, but I had time for no more. I read it through, sanded it and addressed the envelope.

‘Shall you mind having another sister?’ I asked Elizabeth.

‘Not at all. I am looking forward to it. She will live with us at Pemberley?’

‘If you have no objection?’

‘None at all.’

‘She can learn a great deal from you.’

‘And I from her. She will be able to tell me all about the Pemberley traditions.’

‘You must alter anything you do not like.’

‘No, I will not alter anything. My aunt and I are already agreed, Pemberley is perfect just as it is.’

Elizabeth is delighted with Georgiana’s letter, which arrived this morning. It was well written, and in four pages expressed Georgiana’s delight at the prospect of having a sister.

Less welcome was Lady Catherine’s letter.

Fitzwilliam,

I do not call you nephew, for you are no longer a nephew of mine. I am shocked and astonished that you could stoop to offer your hand to a person of such low breeding. It is a stain on the honour and credit of the name of Darcy. She will bring you nothing but degradation and embarrassment, and she will reduce your house to a place of impertinence and vulgarity. Your children will be wild and undisciplined. Your daughters will run off with stable hands and your sons will become attorneys. You will never be received by any of your acquaintance. You will be disgraced in the eyes of the world, and will become a figure of contempt. You will bitterly regret this day. You will remember that I warned you of the consequences of such a disastrous act, but by then it will be too late. I will not end this letter by wishing you happiness, for no happiness can follow such a blighted union.

Lady Catherine de Bourgh

I dined with Elizabeth this evening, and I was surprised to find a large party there, consisting of Mrs Philips, Sir William Lucas and Mr and Mrs Collins. The unexpected appearance of the Collinses was soon explained. Lady Catherine has been rendered so exceedingly angry by our engagement that they thought it wiser to leave Kent for a time and retreat to Lucas Lodge.

Elizabeth and Charlotte had much to discuss, and whilst the two of them talked before dinner, I was left to the tender mercies of Mr Collins.

‘I was delighted to learn that you had offered your hand to my fair cousin, and that she, in her gracious and womanly wisdom, had accepted you,’ he said, beaming. ‘I now understand why she could not accept the proposal I so injudiciously made to her last autumn, when I knew nothing of the present felicitous happenings. I thought at the time that it was strange that such an amiable young woman would refuse the wholly unexceptionable hand of an estimable young man, particularly one who possessed so fine a living, and who, if I may say so, had the advantages of his calling to offer her as well as the advantages of his person. The refusal seemed inexplicable to me at the time, but I fully comprehend it now. My fair cousin had lost her heart to one who, if I may say so, is, by virtue of his standing, more worthy even than a clergyman, for he has the clergyman’s fate in his hands.’

I saw Elizabeth looking satirically at me, but I bore his conversation with composure. I might even, in time, grow to be amused by it.

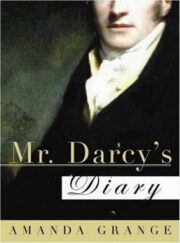

"Mr. Darcy’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mr. Darcy’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mr. Darcy’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.