Thursday 8 April

It was a relief to throw myself into Abbey business today and forget about my neighbours.

Friday 9 April

It is a good thing I am in a better temper today! Emma is arranging a dinner party for the Eltons, and of course I must go, and be polite to Mrs. Elton. I admire the way Emma is bearing it all. I am sure she does not wish to see them, but she is behaving as though nothing unfortunate happened between her and Mr. Elton. I am sure in my own mind that he proposed, or came as close to it as makes no difference. What else would have made him leave Highbury so suddenly after Christmas, if he had not made a declaration and been rejected? So, on the 13th, I must brace myself to hear all about Mr. Suckling and Maple Grove.

Saturday 10 April

An unlucky chance has made my brother choose the day of the party for his visit to Hartfield. He is not fond of company at the best of times, and to have to endure it without his wife present, and with a bridal couple who must be made much of, will be a sore trial to him. I can only hope he will curb his temper, and not upset Mr. Woodhouse.

Emma is worried because it will put her numbers out, and her father’s nerves are on edge because it makes the party bigger than he cares for.

The one good thing is that Harriet has cried off. She does not want to see Elton, I suppose, after Emma put it into her head to think of him.

How the matter of Harriet will resolve itself I do not know.

Monday 12 April

Emma’s problems have been solved in an unexpected way. Weston has been summoned to town, and cannot attend the dinner, though he means to call in afterwards, when he returns, so Emma’s numbers are now perfect.

All is now settled. John arrives tomorrow. He will be calling here first, and then going on to Hartfield, where he will leave the boys.

Tuesday 13 April

My two eldest nephews are growing apace. They are bright, lively boys, and they chased each other round the garden as John and I took a walk. He told me that Isabella and the other three children were well, and that his business is prospering. I took him to see the new path, and he approved of what I had done.

He did not stay long, but soon went on to Hartfield, with the boys being quieter for their run around. They were much more subdued when they arrived at Hartfield than they had been for most of the journey, he told me when I saw him again at Hartfield just before dinner, and they had not put too great a strain on their grandfather’s nerves.

Mr. Woodhouse was as courteous as ever, making the rounds of his guests and paying particular attention to Mrs. Elton, which pleased her greatly. He was very conscious of what was due to her as a bride.

John was talking to Miss Fairfax. He feels, as I do, that her lot is a hard one. To be taken away from everyone she knows and loves, and thrust into another family - one which might be disgreeable, with spoilt children and doting parents - is not an enviable fate.

I have asked amongst my acquaintance and tried to find her a position but I have not had any success. If I could know she was going into a well-regulated household, where her talents would be appreciated, I would be much happier.

My brother was very courteous to her, and as he had passed her on a walk this morning, he asked if she had arrived home before the rain. Fortunately she had, but Mrs. Elton, officious as ever, declared that Miss Fairfax must not walk to the post office any more; Mrs. Elton would have her servant collect Jane’s post.

I admired Miss Fairfax for her tact in dealing with Mrs. Elton. She did not give any direct reply, but instead skilfully turned the conversation towards the post office’s efficiency, and from thence to handwriting, which was a subject much more to her taste, for it meant Mrs. Elton could no longer irritate her.

"Isabella and Emma both write beautifully," said Mr. Woodhouse; "and always did. And so does poor Mrs. Weston," he added, with half a sigh and half a smile at her.

I wonder when he will stop calling her "poor Mrs. Weston"!

"Mr. Frank Churchill writes one of the best gentlemen’s hands I ever saw," said Emma, distracting her father’s thoughts from the sad fate of the woman who sat there, happy and contented, with her husband and her friends about her.

I would have applauded, yet I do not like this habit she has grown into, of forever praising Frank Churchill. Why no one else can see that he is a wastrel with no sense of duty I do not know. I seem to be the only person who is not blind to his faults, and he has many of them.

"I do not admire it," I said, determined to speak my mind. "It is too small - wants strength. It is like a woman’s writing."

Emma did not agree. Perhaps I had gone too far in saying it was like a woman’s hand, but really, I do not see what is so remarkable about Frank Churchill’s writing.

Mrs. Weston was called upon to find a letter, and Emma declared that she had kept a note written by him, and that it was in her writing-desk.

Why has she kept a note written by the man? Is she really falling in love with him? A foolish young puppy, who thinks of no one but himself? Who cannot take the trouble to pay a visit to his own father on his father’s marriage? Who indulges in freaks and whims?

I believe my impatience showed in my reply.

"Oh! when a gallant young man, like Mr. Frank Churchill writes to a fair lady like Miss

Woodhouse, he will, of course, put forth his best," I remarked.

I saw John look at me in surprise, but I could not help myself. Besides, I did not think it was so very rude, although perhaps it was as well that, at that moment, dinner was announced.

Mrs. Elton led the way, as a bride should, and gloried in it, as a bride should not.

Poor Miss Fairfax! I believe she had a great deal to bear after dinner, when the ladies withdrew. When I returned to the drawing-room with the other gentlemen, Mrs. Elton was offering to help her find a position as a governess. I should be sorry to see Miss Fairfax take up a position in any household known to Mrs. Elton.

I was just thinking that things could get no worse when Weston joined us. As luck would have it - or as bad luck would have it - he brought with him a letter from his son.

I took up my newspaper. I had no desire to listen to any further praise of Frank Churchill’s magnificent handwriting.

The letter was even worse than I had expected. A string of promises, a row of false hopes, all wrapped up in insincerity and capriciousness; that was what I had expected. But instead I learnt that the Churchills are to remove to town on account of Mrs. Churchill’s health, and that Frank is to remove with them. He will be so close to Hartfield - only sixteen miles away - that he will be able to visit easily.

Mr. and Mrs. Weston were delighted. Emma was delighted. And I was not delighted.

"We have the agreeable prospect of frequent visits from Frank the whole spring," Weston said.

Agreeable to whom? I thought, rustling my newspaper.

"Precisely the season of the year which one should have chosen for it: days almost at the longest; weather genial and pleasant, always inviting one out, and never too hot for exercise. When he was here before, we made the best of it; but there was a good deal of wet, damp, cheerless weather; there always is in February, you know, and we could not do half that we intended. Now will be the time. This will be complete enjoyment; and I do not know, Mrs. Elton, whether the uncertainty of our meetings, the sort of constant expectation there will be of his coming in today or tomorrow, and at any hour, may not be more friendly to happiness than having him actually in the house. I think it is so. I think it is the state of mind which gives most spirit and delight."

In May, then, I am to have all the pleasure of Frank Churchill’s company, as long as I do not expire before then with the promise of so much spirit and delight.

Fortunately, John began to speak of his sons before my bad temper could get the better of me.

"I hope I am aware that they may be too noisy for your father; or even may be some encumbrance to you, if your visiting engagements continue to increase as much as they have done lately," he said to Emma.

"Let them be sent to Donwell," I said. "I shall certainly be at leisure."

"Upon my word," exclaimed Emma to me, "you amuse me! I should like to know how many of all my numerous engagements take place without your being of the party; and why I am to be supposed in danger of wanting leisure to attend to the little boys. If Aunt Emma has not time for them, I do not think they would fare much better with Uncle Knightley, who is absent from home about five hours where she is absent one - and who, when he is at home, is either reading to himself or settling his accounts."

I smiled at this. She knows me well.

Mrs. Elton claimed my attention, but when she had done, I went to sit by Emma.

"You will bring the boys over to the Abbey tomorrow? If the weather continues wet, it will give them a chance to run about and be noisy without distressing your father."

"By all means. Harriet is to call in the morning, and we will bring them together."

"Must you always be with Harriet?" I asked impatiently.

"That is hardly fair!" she cried. "I have seen very little of Harriet since…"

"Since Mr. Elton returned?" I enquired. I saw her look uncomfortable, but I let it pass. "Very well, if you must bring her, you must." I had done with Harriet. "I want to give the children a chance to ride whilst they are here," I went on. "It is not often we have them for such an extended spell."

"Oh, yes, they are full of high spirits and are bound to enjoy it. But it is perhaps better not to mention it to my father; he will only worry about it. I hope the weather holds."

"There will be some dry spells, I am convinced."

"And if it rains tomorrow?"

"Then you and I will have to entertain the boys indoors."

I am looking forward to it. Inside or out, any time I spend with the boys is well spent, and I would never rather be with anyone but Emma.

Wednesday 14 April

I cannot make up my mind. Is Emma in love with Frank Churchill, or is she not? I sometimes think she is, but then she says something that convinces me otherwise. She seems to welcome his attentions, and yet she has not shown any signs of being in a decline when he is away.

We were talking of Isabella’s living in London, and I said to Emma: "Could you bear to move away from Highbury?"

"If there was a strong enough inducement, then perhaps I might," she said.

I thought of Frank Churchill. Would he be a strong enough inducement?

"Isabella seems happy enough in London," she went on, "but then she is happy wherever her husband is."

"And when you marry, you will be happy wherever your husband is," I said, looking at her earnestly.

"I will never marry," she said. "Why should I? I already have everything I want at Hartfield. Like you, I have no need of children to interest me, for I have Isabella’s children, and like you, I am happiest at home."

I felt myself grow brighter. It is very comfortable to have Emma so near, and spending my time with her, playing with the children, is my idea of a perfect day.

Thursday 15 April

There has been a delay in the Churchill family’s move to London. I knew how it would be! Churchill’s letter meant nothing at all. I never put any reliance on it. What! Mrs. Churchill, to remove to London from her native Yorkshire? Why should she do such a thing? And even if she thought she might, then why should she go ahead with her plan, when she is as fickle as her nephew?

I said as much to Emma.

"It is hardly Frank Churchill’s fault," she said. "He is very much at his aunt’s beck and call. He will be with us as soon as he can."

She did not seem unduly worried by the delay, which was heartening, but she defended him, which was dispiriting.

I still do not like the idea of his merely being delayed for a while. Whenever he comes to Highbury, it will be too soon for me.

Wednesday 21 April

I had a most unwelcome shock when I went to Hartfield today. I had promised to collect the boys, so that they could spend a day at the Abbey with me, and when I walked into the drawing-room, I found Frank Churchill there!

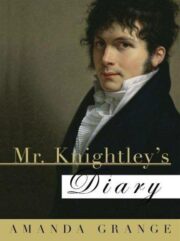

"Mr. Knightley’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mr. Knightley’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mr. Knightley’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.