Mrs Grant was clearly of the same mind; she went immediately to her writing-desk, and penned a short note to Lady Bertram. "If you will be so good as to take that to the Park," she said, holding it out to the workman. "And with all speed, if you please."

"Yes, ma’am," he said, bowing, and with a parting look at Mary, he was gone.

The apothecary was not long in arriving thereafter; it was lucky for them that he was close by, having been attending a case of pleurisy in Mansfield-common, and he was able to give his opinion on the invalid without delay.

"I am afraid, Mrs Grant, that it is a very serious disorder," he said, shaking his head. "Her strength has been much weakened, and in consequence the danger of infection is very great. I will prescribe a cordial for you to administer, and you must convey her upstairs to bed at once. On no account should she be moved unnecessarily. I will call again later today."

"Thank you, Mr Phillips, you may rely on us," said Mrs Grant. "I will see you to the door."

When Mrs Grant returned to the parlour she found Mary sitting at Julia’s side, her eyes filled with tears. "I should have foreseen this!" she said. "I knew she had been neglecting her health — I knew she was half frantic about the felling of the avenue — I should have talked to her — comforted her — "

Mrs Grant sat down next to her, and took her hands in both her own. "I am sure you did everything you could, Mary. I know your kind heart, and I know your regard for Miss Julia. This latest folly of hers was in all probability the whim of the moment — how could you possibly have anticipated she would do such a thing? And on such a night!"

Mary wiped her eyes. "It was her last chance," she said softly. "They were to start the felling today. She must have been truly desperate."

"Come, Mary," said her sister, kindly, "the best way for us to shew our concern is by ensuring she is well cared for. The maids have prepared the spare room, and lit a good fire. Let us ask Baker to carry her upstairs."

Mrs Grant went in search of the man-servant, and Mary was left for a few moments to herself — a few moments only, for she was soon roused by a loud knocking at the door, followed, without announcement, by the unexpected appearance of Mrs Norris. This lady looked exceedingly angry, and seemed to have recovered all her former spirit of activity; she immediately set about giving loud instructions to the maids, and directing her own servants to carry Julia to the waiting carriage. Mary intervened most strenuously, citing the apothecary’s advice, her own concerns, and the certainty of the best possible care under Mrs Grant’s good management, but to no avail. Mrs Norris was not to be denied, and even the reappearance of Mrs Grant herself could not dissuade her.The two were seldom good friends: Mrs Norris had always considered Mrs Grant’s housekeeping to be profligate and extravagant, and their tempers, pursuits, and habits were totally dissimilar. One of the Mansfield footmen was already lifting Julia in his arms, when Mary made one last attempt to prevent what must, she believed, be a wretched mistake.

"I beg you, Mrs Norris, not to do anything that might endanger Miss Julia any further. Mr Phillips was most definite — she was not to be moved."

"Nonsense!" cried Mrs Norris, turning her eyes on Mary with her usual contempt. "What can you know of such things? I have been nursing the Mansfield servants for twenty years — Wilcox has been quite cured of his rheumatism, thanks to me, and there were plenty who said he would never walk again. And besides, we have our own physician to consult — quite the best man in the neighbourhood, I can assure you. Not that it is any of your concern. What are you standing there gaping for, Williams? Hurry up, man — take Miss Julia to the carriage!"

"In that case," said Mary firmly, "I hope you will permit me to accompany you back to the Park. It would comfort me to know that Mr Phillips’s instructions were conveyed correctly."

"That is quite ridiculous!" cried Mrs Norris, her face red. "Absolutely out of the question! Even if there were room in the carriage, how dare you suggest that I cannot comprehend the instructions of a mere apothecary, or that the Bertrams are incapable of caring properly for their own daughter!" And with that she turned, and without the courtesy of a bow, swept out of the room.

Mary was about to follow her when Mrs Grant put a hand on her arm. "Let her go, sister.You know it is useless to remonstrate with her when she is in such a humour as this."

But Mary was not to be restrained, and shaking herself free, she ran out of the house towards the carriage, only to stop a moment later in amazement and confusion. For who should she see helping to settle Julia into the carriage, and arranging the shawls gently about her, but Edmund! She had been thinking him two hundred miles off, and here he was, less than ten yards away. Their eyes instantly met, and she felt her cheeks glow, though whether with pleasure or embarrassment she could not have told. He was the more prepared of the two for the encounter, and came towards her with a resolute step, ignoring his mother’s agitations to be gone.

"Miss Julia is most unwell," faltered Mary. "The apothecary — he was concerned at the harm that might be caused by such a removal — I do not think Mrs Norris — "

"My mother can be very resolute, once she has determined on a course of action," he replied, with a grim look, "but once I understood her design in coming here, I insisted on accompanying her. You may trust me to ensure that the journey causes Julia the least possible discomfort, and that she will have every attention at the Park."

"And your own journey?" she asked quickly. "You must have arrived very recently."

"This very hour," he said, with a look of consciousness. "I am sure you will be relieved to hear that Sir Thomas improves daily, but Mansfield is a very different place from the one I left. You, I know, will understand — "

At that moment they were interrupted once again by the sharp voice of Mrs Norris from her seat in the carriage. "I thought Miss Crawford professed herself concerned for Julia’s health. In which case I cannot conceive why she is deliberately delaying our departure in this way, and forcing the carriage to wait about in this heat. That will do Julia no good at all, you may be sure of that."

Edmund turned to Mary. "Perhaps you would do us the honour of calling at the Park in the morning?" he said quickly, with a look of earnestness. "You will be able to enquire after Julia, and perhaps I might also take the opportunity to have some minutes’ converse with you, if it is not inconvenient."

"Yes — that is — no, not at all. I will call after breakfast."

He bowed briefly, and the carriage was gone.

Mary kept her promise; indeed, she could not suppress a flutter of expectation as she dressed the following morning, and rejoiced that the continued sunshine made it possible for her to wear her prettiest shoes, and her patterned muslin. She knew she should not be happy — how could she be so when the family at the Park was labouring under a threefold misery? Even if the news from Cumberland continued to improve, there had been no tidings of Fanny, and at that very moment Julia might be dangerously ill; but whatever Mary’s rational mind might tell her, her heart whispered only that she was to see Edmund — and an Edmund who was now, for the first time in their acquaintance, released from an engagement to a woman who had evidently never loved him, and whom, perhaps, he had never loved. Whatever her feelings ought to have been on such an occasion, hope had already stolen in upon her, and Mary had neither the wish nor the strength to spurn it.

But whatever joyful imaginings might captivate her in the privacy of her chamber at the parsonage, every step towards the house reminded her of the wretched state the family must be in, and her duty to offer what comfort she could, without thought for herself. By the time she rang the bell at the Park she had reasoned herself into such a state of penitent selflessness, as to almost put Edmund out of her mind, only to find that all the ladies of the Park were indisposed, and unable to receive visitors. She should, perhaps, have expected such a reception, but she had not, and stood on the step for a moment, feeling all of a sudden exceedingly foolish, her good intentions as vain and irrelevant as her good shoes. She recovered herself sufficiently to leave a message enquiring after Julia, but the very instant she was turning to go, the housekeeper happened to cross the hall with a basin of soup, and glimpsing Mary at the door, hurried over at once to speak to her. She was a motherly, good sort of woman, with a round, rosy face. Even had Mary been in the habit of chatting with servants, Mrs Baddeley was rather too partial to gossip for Mary’s fastidious taste, but the circumstances being what they were, she swallowed her scruples and accepted the offer of a dish of tea in the housekeeper’s room. Mrs Baddeley was soon bustling about with cups and saucers, while Mary listened to her account of Julia’s restless and feverish night with growing concern.

"I don’t think the poor little thing slept a wink all night, that I don’t, Miss Crawford. Tossing and turning and moaning she was, babbling one minute, and as good as dead the next. And that terrible rash all over her poor arms. Mr Gilbert came again at first light, and has been with her these two hours, but I doubt he has seen ought like it, for all his notions and potions."

"I am very sorry to hear it, Mrs Baddeley," Mary replied, her heart sinking.

"Between ourselves," said the housekeeper, moving a little closer, "I think you was right to tell Mrs Norris she shouldn’t have been moved. That will be at the root of the mischief, you mark my words."

Mary flushed. "I am not sure I take your meaning — how did you know that I — "

Mrs Baddeley gave a knowing look. "Servants may be dumb, Miss Crawford, but we be not deaf into the bargain. Young Williams, the footman who carried Miss Julia to the carriage, he told my Baddeley what you said, and he told me. There be no secrets in the servants’ hall, whatever our betters might choose to believe."

Mary had never doubted it; she had once been a housekeeper herself in all but name, and had learned more about human nature from those few short years than she had from all her books and schoolmasters, even if it was an experience she now preferred not to dwell on, at least when among genteel company.

"If you ask me, the ladies could do with having someone like you in the house, Miss Crawford," continued Mrs Baddeley. "The whole place is at sixes and sevens. Are you sure I cannot fetch you a piece of cake? Very good cake it is, made to my mother’s own receipt."

"No, thank you, Mrs Baddeley."

Her companion settled her ample form more comfortably into her chair. "I’m sure I don’t need to tell you that her ladyship is of no use in a sick-room, and Miss Maria isn’t much better — from the moment they brought her sister back yesterday she’s been all but frantic — crying and falling into fits, and needing almost as much attention as poor Miss Julia."

"And Mrs Norris? As I understood it, she was to take charge of the nursing."

"Well, if you call it taking charge. There’s been a lot of shouting and bawling, and calls for footmen in the middle of the night, but not much of any use, in my opinion. If you ask me, she’s never got over the shock of Miss Fanny taking off like that. That marriage was going to be the making of her. Her and Mr Norris both."

The mention of Edmund’s name recalled Mary to herself, and she hastened to thank Mrs Baddeley for her tea and depart, before she found herself made the confidante of observations of an even more awkward nature.

She had almost given up any hope of seeing Edmund, but as she went back up the stairs she saw him at the outer door in the company of Sir Thomas’s steward. The two were deep in serious discussion, and it was several moments before they became aware of her.

"My dear Miss Crawford," said Edmund at once, "do forgive me. I have been engrossed, as you can see, with Mr McGregor." He stopped, momentarily discomfited. "I recall now that you were so good as to agree to call on us today. I have had so much to attend to since my return that my mind has been too much engaged to fix on anything else. Were you able to see my cousin?"

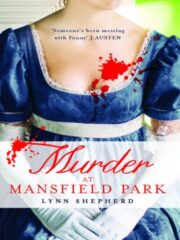

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.