O’Hara gave a short laugh. "Mine, to be sure! She might ’a looked as if butter wouldn’t melt, but I’ve seen the looks she gave Miss Maria, when she thought she’d stole that Mr Rushworth from her. We all thought as it were him she ran off with, but it seems it must "a been someone else entirely."

"You have no suspicion of who that might have been?"

O" Hara drained her glass, and put it down; her cheeks were somewhat flushed. "If it ’a been me, I’d ’a gone off with that Mr Crawford as soon as look at him. He’s a fine gentleman, and no mistake."

"But since Mr Crawford was not in the neighbourhood at the time — "

O’Hara shrugged her shoulders. "All I can say is she definitely meant to meet someone that morning. That pelisse she was wearing? It was the best she had, and she had some beautiful things. She wouldn’t ’a worn that for a walk in a muddy garden with no-one round to see."

Maddox nodded thoughtfully; Mary Crawford had made a similar observation, but it had taken this girl’s rude simplicity to make its full meaning manifest. He decided it was time to question her more minutely on the matter in hand.

"Do you know of anyone who might have wished Miss Fanny harm?"

O’Hara’s eyes widened in alarm. "Killed her, you mean? I can’t tell you anything about that — I don’t know nothing about it, and that’s God’s honest truth."

Maddox cursed himself; terror would only petrify her into silence. "No, no, do not fret about that. I only wish to know the real state of things between Miss Fanny and her relations."

O’Hara gave him a narrow look. "I suppose there’s no harm in telling what everyone here knows — "

"No, indeed, Hannah, and especially when it is what everyone knows, but no-one will say. No-one in the family, that is."

O’Hara gave him a penetrating glance. "They didn’t know the half of it. Not Sir Thomas and her ladyship, anyways. It always looked peaceful and good humoured enough on the surface, but underneath it was a different story, make no mistake about it. At least as far as the young ladies was concerned. Miss Fanny had a cunning way of her own of causing quarrels without seeming to, if you take my meaning. And as soon as Miss Maria set her cap at Mr Rushworth, well, you can just imagine what Miss Fanny thought ’a that — I think it truly was the first time in the whole course of her life that she’d ever wanted something and not got it at the first time of asking. The bickerings that man caused! Miss Maria did what she could to stand her ground, but she never had cat’s chance — Miss Fanny would bawl at her like a trollop when they were out of hearing of the rest of the family, however dainty and demure she made sure to look in the drawing-room."

O’Hara sat back in her chair, and eyed Maddox in a conspiratorial manner. "If you ask me, something happened on that jaunt to Compton. I can’t tell you as to what, but everything changed after that and it weren’t just the news about Sir Thomas.You see if I’m not wrong."

Maddox did not rise to the bait. "And what about Mr Norris — how did he feel about all this?" he continued.

O’Hara did not appear to be particularly interested in Mr Norris. "Oh, you never could tell, with him. He’s a deep one — keeps his feelings to hisself. But one of the footmen saw what happened when he got back from Cumberland the first time and caught Miss Fanny and Mr Rushworth at that play rehearsal. She was in his arms, so Williams said. Almost kissing, he said. Not at all what a man like Mr Norris would have expected, I can tell you. Williams said his face was black as thunder, and he insisted the whole thing was stopped, right there and then. It was the talk of the servants’ hall for days after."

Maddox could well believe it; O’Hara, meanwhile, was still speaking.

"All the same, if you ask me, he was as tired of her, as she was of him. It wasn’t just about Mr Rushworth, either. They both preferred someone else."

Maddox sat forward in his chair; he had already discovered, or guessed, much of what O’Hara had told him, but this he had not heard before.

"Oh, he did his best to hide it," she said, "being so strict and all, but you only had to look at him when she was in the room. He was in love with her. It was written all over his face."

"It is most important there is no misunderstanding about this point, Hannah," said Maddox choosing his words with care. "To whom are you referring?"

"Why, Miss Crawford, of course. Who else could it be?"

Even though the hour was late, Maddox sent Stornaway to fetch Maria Bertram’s maid, and sat over the fire while he awaited her arrival, perusing the notes Fraser had taken. He also read once again the observations he himself had recorded after his conversation with Mary, in the light of O’Hara’s last and most suggestive revelation.

It was all very interesting, very interesting indeed.

Chapter 14

Mary, needless to say, knew nothing of this; and she set out for the Park the following morning with a heart much lighter than it would have been, had she been privy to all that was going through Maddox’s mind at that same moment. The house seemed quiet enough, and if the servants were more circumspect than usual, Mary scarcely noticed in her eagerness to enquire after Julia, and her relief at hearing that if she was no better, she was likewise no worse. The girl had been given another sleeping draught, and Mary sat with her for some time, deriving considerable comfort from seeing her in such a quiet, steady and seemingly comfortable repose. From the window she could still see the view that had been so much cherished by her young friend. Mary could not but find it most affecting that, even if it had come about in a way she could never have foreseen, Julia had, indeed, succeeded in her desperate attempt to save her beloved trees: they had been judged sufficiently close to the Park to make the task of felling them too productive of noise and commotion for the abode of a patient in her precarious state of health. A temporary stay of execution had since become indeterminate; the workmen had been confined to their quarters since Mr Maddox’s arrival, at his express request, and Mary now doubted whether the improvements at Mansfield Park would ever be resumed.

She was still pondering the effect all this might have on Henry, as she made her way down the main staircase some time later, and saw Maddox in deep conversation with his two assistants in the entrance hall; Maddox was wearing yet another fine and expensive frock-coat, while the men were in riding-dress, and to judge by their appearance, had been on horseback that morning. They were evidently discussing a matter of great import with their employer, and the taller of the two pointed more than once at a piece of paper he held in his hand. As Mary drew closer Maddox made towards her, with a smile that spoke of a development of some significance.

"My dear Miss Crawford!" he said, with a smile. "You will be pleased to hear that I have already made considerable progress. My men have been enquiring at local inns hereabouts, and have discovered that a young lady answering Miss Price’s description was seen at the White Hart in Thornton Lacey some four days past. She was observed alighting from the London coach that evening, and, given the foul weather, decided to take a room for the night.The landlord says she would not give her name, and seemed concerned to muffle herself up in her cloak as much as she was able, and avoid all intercourse with other guests. She then hired a pony and trap early the following morning, but has not been seen since; indeed the landlord begins to be somewhat incommoded by the vast quantity of trunks and band-boxes she left behind."

It took some moments for Mary to comprehend the full import of his words, and her thoughts returned at once to her conversation with Tom Bertram. She knew that Fanny had been in no want of money when she left Mansfield, but the purchase of such a number of new clothes and effects seemed, once again, to argue for an elopement. And yet she had returned alone just as she had left, and wearing no ring. It was inexplicable. But at that moment, Mary became aware, on a sudden, that Maddox’s eyes were fixed upon her.

"I congratulate you, sir," she said quickly, wondering whether this was the response he had expected, "you have been most thorough.What did the owner of the pony-trap have to say?"

Maddox inclined his head. "It is my turn to congratulate you, Miss Crawford; that is exactly the question I myself asked. Happily, Stornaway encountered no difficulties in tracking the man down, and has only recently returned from examining him. The man was barely coherent, I am afraid, and a little the worse from spending most of last night in the inn, but it seems the young lady demanded to be set down at the back gate of the estate; the man has not lived long in the neighbourhood, and had no idea that his early morning passenger was the celebrated Miss Price of Mansfield Park. He did remember that it had been raining hard, and the weather still looked ominous, and the young woman did not seem to be shod for walking — as you yourself pointed out to me only yesterday, Miss Crawford. He expressed some concern for her boots as Miss Price was getting down from the trap, but all he received by way of reply was a rather tart little remark about there being “plenty more where those came from”. Curious, would you not say? And now, if you would be so good as to accompany me to the drawing-room?"

"I do not understand — "

"Fear not," he said cheerfully, already some yards ahead of her. "It will all become clear, soon enough."

When the footmen threw open the doors Mary was startled to see that the whole family was assembled, with the sole exception of Julia Bertram. Lady Bertram and her elder daughter were sitting silently on the sopha; Mrs Norris was in her customary chair; Edmund stood by the French windows, his back to the company; and Tom Bertram was standing before the fire, his hands behind his back, in just such a position as his father might have assumed. All were wearing deep mourning, which only served to add to the portentous mood of the room.

Mary turned at once to Maddox. "There must be some mistake — you cannot require my presence here — "

"On the contrary, Miss Crawford," he said, taking her firmly by the arm, "I have a question I must put to everyone at Mansfield, and it will save a good deal of time if I may ask you that question now, rather than being compelled to make a separate journey to the parsonage later in the day."

"Very well," said Mary. She knew she must look as confused and perplexed as any of them, and with an attempt at self-possession that was far indeed from her true state of mind, she walked silently towards the sopha, and sat down next to Maria.

Maddox assumed a place in the centre of the room, and began to pace thoughtfully up and down the carpet; his mind seemed elsewhere, but he could hardly be unaware of the eyes fixed upon him, or the painful apprehension his behaviour was occasioning. Mary looked on, conscious of the variety of emotions which, more or less disguised, seemed to animate them all: Maria seemed concerned to affect an appearance of haughty indifference, while a dull grief was discernible in her mother’s face; Tom Bertram looked serious, and Mrs Norris furious and resentful; of Edmund’s humour she could not judge.

"May I begin by thanking you for your prompt compliance with my request for an audience this morning," Maddox began, in a manner that was perfectly easy and unembarrassed."As I have been explaining to Miss Crawford, I have just now received certain most interesting information. We have, at last, a witness." He stopped a moment, as if to ensure that his announcement would produce the greatest possible effect.

"Miss Price was seen by a local man, at the back gate to Mansfield, three mornings ago, some time between eight and nine o’clock. Since she never reached the Park, I believe we may safely presume that she met her death at, or around, that time."

There was a general consternation at this: Edmund turned abruptly round, his face drawn in shock and dismay; Maria gasped; and Lady Bertram drew out her handkerchief and began to cry quietly. Mary was, perhaps, the only one with sufficient presence of mind to observe Maddox at this moment, and she saw at once that he was equally intent on observing them. "So he has contrived this quite deliberately," she thought; "he plays upon our feelings in this unpardonable fashion, merely in order to scrutinise our behaviour, and assess our guilt." But angry as she was, she had to own a reluctant admiration for his method, even if it owed more to guile and cunning, than it did to the accustomary operations of justice. There doubtless were inveterate criminals so hardened to guilt and infamy as to retain control over their countenances at such a moment, but the members of the Bertram family could not be numbered among them. Maddox had succeeded in manoeuvring them all into displaying their most private sentiments in the most public fashion.

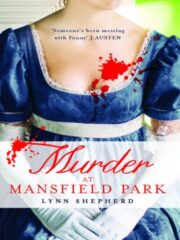

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.