She spoke in a cross tone quite unlike her usual simper, which Mary took as proof that discontent and jealousy had made her briefly forgetful of the appearance of demure and tender sensibility she normally studied to affect. The effect of her words on Julia was equally apparent; it pained Mary to see that the girl had turned of a death-like paleness, and was too intent on suppressing her agitation to eat or speak anything more.

"I quite agree with you, Fanny," said Mrs Norris quickly. "Indeed, I was saying much the same to Lady Bertram only this evening. At fourteen Julia is in far too many respects exactly as she was at ten. Running about wild in the woods, tearing her clothes, and indulging in all manner of juvenile whims. If you had seen her in the drawing-room the other day, Sir Thomas — quite ragged and covered with paint from head to toe! I am sure you would have agreed with me — it is time she was taken in hand. I am at your service, sir, whenever you command me."

As a general reflection on Julia, Sir Thomas thought nothing could be more unjust, and seeing that his daughter’s tears were about to shew themselves, he tried to turn the conversation, tried repeatedly before he could succeed, but the volubility of his principal guest came at last to his aid. Mr Rushworth was a great deal too full of his own cares to think of anything else, or notice what had passed, and he resumed the subject of improvements in general, and Sotherton in particular, with unimpaired enthusiasm. After a lengthy description of the work he was intending to undertake — which was all to be done in the very best taste and without a thought for the expense — he returned once more to Compton, which he now appeared to consider owed all its picturesque new beauty to his having once had a brief conversation on the subject with its owner, more than a twelvemonth before. Mary hardly dared look at her brother, but when she did have the courage to glance across at him, she found to her surprise that he was deep in conversation with Miss Price. Judging by that young lady’s expression, Henry was doubtless supplying all the compliments Mr Rushworth had neglected to provide, but Mary wondered at the wisdom of such a proceeding for either party. Miss Price might make use of her brother’s flattery to console a wounded vanity, and he might profit from such a capital opportunity to advance his own suit, but in neither case could Mary see much good resulting from it, and a glance at Mr Norris shewed that he was not entirely free from similar apprehensions. Mary could not but agree, though to think of Edmund as agitated by jealousy, was a bitter blow indeed.

Mr Rushworth concluded his discourse with a second and even more lengthy expatiation on the new prospects that had been opened up by the felling of the avenue, and turned in conclusion to Julia, seemingly unaware that he was only adding to her distress. "But if the youngest Miss Bertram is still unpersuaded, and would prefer some blasted tree-trunks to the openness of a fine view, perhaps a visit to Compton might convince her?"

"It is a capital idea, Rushworth," said Tom quickly, "but unhappily Mr Smith is not among our acquaintance, though perhaps Mr Crawford might be able — "

"Oh! If that is all the difficulty, then you need say no more," replied Mr Rushworth in a grand way. "Smith is an intimate friend of mine, and that alone will suffice to gain admittance. It is, what? Ten or twelve miles from Mansfield? Just the distance for a day’s excursion. We may take a cold collation à la rustique, and wander about the grounds, and altogether enjoy a complete party of pleasure."

Miss Bertram clapped her hands together, her eyes sparkling with anticipated enjoyment; even Miss Price smiled her acquiescence, and Sir Thomas was pleased to give his approbation; but the person for whose benefit the visit had been proposed, remained wholly unmoved. Julia looked first at Henry and then at her father, and then, rising from her chair, she ran out of the room, dashing her plate to the floor. There was an awkward pause before Lady Bertram rose, and suggested to the ladies that this would be an appropriate time for them to withdraw. Mary wondered if she might contrive to see Julia, and console her, but not knowing where she might find the girl’s room, she was obliged to hope a member of the family would shew a similar solicitude; though as far as she could ascertain, no-one slipped away upstairs, either then, or at any other time that evening.

When the ladies attained the drawing-room the subject turned immediately to their visitor. Mr Rushworth was not handsome; no, was Miss Price’s judgment, he was absolutely plain — small, black, and plain. Further impartial consideration by Miss Bertram proved him not so very plain; he had so much countenance, and his nose was so good, and he was so well made, that one soon forgot he was plain; and after a quarter of an hour, she no longer allowed him to be called so by any body, whatever Miss Price’s views were on the matter. Mr Rushworth was, in fact, the most agreeable young man Miss Bertram had ever met; Miss Price’s engagement made him in equity the property of her cousin, of which she was fully aware, even without the nods and winks of Mrs Norris, and by the time the gentlemen appeared, she was already wrapt in her own private and delicious meditations on the relative merits of white satin and lace veils.

When the gentlemen joined them a few minutes later, it became apparent that they had been talking of a ball; and no ordinary ball, but a private ball in all the shining new splendour of Sotherton, with its solid mahogany, rich damask, and bright new gilding. How it came that such a capital piece of news should have fallen to the share of the gentlemen and the port, the ladies could not at first comprehend, but the fact of the ball was soon fixed to the last point of certainty, to the great delight of the whole party. In spite of being somewhat out of spirits, the prospect of a ball was indeed delightful to Mary, and she was able to listen to Mr Rushworth’s interminable descriptions of supper-rooms, card-tables, and musicians, with due complacency. Miss Bertram had never looked so beautiful, and Mary was almost sure that in the general bustle and joy that succeeded Mr Rushworth’s announcement, he had taken the opportunity to speak to her privately, and secure her for the two first dances. As for Miss Price, there could be no doubt whom she would open the ball with, but when Mary looked around for her, she found that she was, once again, engaged in an animated conversation with Henry, while Edmund was standing alone by the fire, lost in thought.

The following morning Mary called early at the Park, only to find that Julia Bertram was indisposed and in bed. Having sent her best compliments to the invalid, she was on the point of departure when she found herself being ushered with some ceremony into the morning-room, where the other ladies of the house were assembled. After paying her respects to Lady Bertram, who was sitting on the sopha on the other side of the room, absorbed in her needlework, she saw Miss Price gesturing to her, and as soon as Mary drew near she said in a low voice, "May I speak to you for a few minutes? I wish to ask your advice."

The look of surprise on Mary’s face shewed how far she was from expecting such an opening, but Miss Price rose immediately and led the way upstairs to her own room. As soon as the door closed behind them, Miss Price began to explain the nature of her request.

"It is the ball at Sotherton that I seek your advice upon, Miss Crawford. I am quite unable to satisfy myself as to what I ought to wear, and so I have determined to seek the counsel of the more enlightened, and apply to you."

Miss Price then proceeded to lay before her such a number of elegant gowns, anyone of which might bear comparison with the latest London fashions, as left Mary in no doubt that Miss Price had no real value for her opinion, and wanted only to display her own superior wardrobe. For the next two hours Mary was obliged to listen to a minute enumeration of the price of every head-dress, and the pattern of every gown. Her own dress being finally settled in all its principal parts, Miss Price turned her attention to Mary.

"And what will you wear, Miss Crawford? The gown you wore at dinner last night? Or do you have another? And what about ornaments? Do you possess anything that would be considered rich enough for company such as we shall have at Sotherton?"

"I have attended assemblies in London many times," said Mary firmly, "and I have always worn a very pretty topaz cross that Henry bought for me some years ago."

"I recollect the very one!" cried Miss Price, "but do you really have only that meagre bit of ribbon to fasten it to? Surely Mr Crawford might be prevailed upon to buy you a gold chain as well?"

"Henry had wanted to buy me a gold chain," said Mary, concealing her anger, "but the purchase was beyond his means at the time."

"But surely, not to wear the cross to Mr Rushworth’s ball might be mortifying him?"

"My dear Miss Price, such a trifle is not worth half as many words. Henry will be delighted to see me wearing the cross, even on a piece of meagre ribbon, and I do not care for anyone else’s opinion, whatever it may be."

"Not care how you appear in front of so many elegant young women! I would be ashamed to stand up so. My dear Miss Crawford, pray let me be of assistance."

Turning to her table, she immediately presented Mary with a small trinket-box, and requested her to choose from among several gold chains and necklaces.

"You see what a collection I have," said she grandly, "more by half than I ever use, or even think of. My family is always giving me something or other. I do not offer them as new, I offer nothing but an old necklace. You must forgive the liberty and oblige me."

Mary resisted for as long as she could without being thought ungrateful, wondering all the time what Miss Price’s real motive might be in such a shew of generosity; but when her companion urged her once again, Mary found herself obliged to yield, and proceeded to make the selection. She was determined in her choice at last, by fancying there was one necklace more frequently placed before her eyes than the rest, and she hoped, in fixing on this, to be choosing what Miss Price least wished to keep. She would rather perhaps have been obliged to some other person, but there was nothing to be done now, but to submit with a good grace and hope for the best.

Chapter 5

The weather remaining resolutely unsettled, the proposed excursion to Compton was postponed. Luckily the young people of Mansfield had another prospect of pleasure, and one that promised yet keener delights. Invitations to the Sotherton ball were sent with dispatch, and Mr Rushworth calculated to collect young people enough to form twelve or fourteen couple. He had fixed on the 22nd as the most eligible day; Sir Thomas was required to depart for Cumberland on the 24th and was to be accompanied on the first stage of the journey by Mr Norris. The preparations duly began, and Mr Rushworth continued to ride and shoot without any inconvenience from them. He had some extra visits from his housekeeper, his painters were rather hurried in finishing the wainscot in the ball-room, and all the while Mrs Norris ran about, enquiring whether she or her housekeeper might be of any assistance, but all this gave him no trouble, and he confidently declared that, "there was in fact no trouble in the business".

As for Mary, she had too many agitations to have half the enjoyment in anticipation which she ought to have had, but when the day came she awoke in a glow of genuine high spirits. Such an evening of enjoyment before her! She began to dress for it with much of the happy flutter which belongs to a ball. All went well — she had chosen her finest gown, and left her room at last, comfortably satisfied with herself and all about her.

Henry was impatient to see Sotherton, a place of which he had heard so much, and which held out the strongest hope of further profitable employment, and as they drove through the park he let down the side-glass to have a better view.

"Rising ground," he commented, "fine woods, if a little thinly spread, and the pleasure-grounds are tolerably extensive. All in all, very promising. I must make more of an effort to be civil to our Mr Rushworth in future. After all, if he can employ Bonomi for the house, he can certainly afford Crawford for the park."

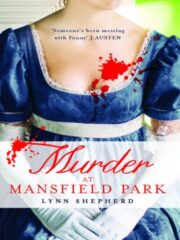

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.