His father put his arm around Theo and squeezed hard. “Trust me when I say you’re in over your head. And what about your mother?”

“What about her?”

His father turned Theo’s face by the chin. “What am I supposed to do? Keep this from her?”

“Yeah,” Theo said. “I mean, you can’t tell her.”

“Well, then, you shouldn’t have told me.”

“Except you’re my father.”

“That’s not going to work, Theo. I’m not getting warm, fuzzy father-son feelings about this conversation. Because what you’re telling me spells danger for you and for your mother. You especially. You’re going to get creamed in this, I promise. Antoinette is too old, too sophisticated, too goddamned complicated. But mostly too old. Do you hear me? Now, I understand wanting to get laid. I understand that part just fine. But not Antoinette.” He put his hands on the windowsill and leaned through the empty window. “What the hell is that woman thinking? You’re just a kid.”

“I’m an adult,” Theo said. “Eighteen, right? Old enough to go to war and all that.”

“It’s wrong,” his father said. “What Antoinette is doing is wrong.”

“It’s not her fault,” Theo said. “Please don’t say anything to Antoinette.”

“Well, it’s over now. I’m making it over.” Theo’s father blew air out his nose, like a bull ready to charge. “You’re forbidden from going over there again.”

“You can’t forbid me to do anything.”

“I sure can. I’m your father.”

“What about you always telling us to make our own choices, to develop our independence? What about that? Was that all bullshit?”

“This isn’t a sound choice, Theo.”

“Just let me deal, okay? I told you because, well, because I needed to tell somebody, and you asked. Whatever, just let me make this mistake if that’s what this is.” He poked his father in the back. “If you tell Mom, I’ll kill you.”

“Don’t threaten me, mister.”

Theo kicked some more nails, then a hammer. What he needed was some help, some understanding. Didn’t his father see that?

“Just forget it,” Theo said. He left the house, got in his Jeep, and headed home.

Theo studied his mother for any sign of change and saw none. So there was that. Either his father respected his decision or he was too afraid to tell Theo’s mother the truth. His father was cold with him, distant, and that hurt because his father wasn’t home that often anyway, and so Theo went from getting a small amount of his father’s attention to none at all. So what could Theo think but, Fuck him? All his father cared about was building some huge house that-according to the principles of 300 Years of Nantucket Architecture-would ruin the character of the island forever.

…

And then, Antoinette missed her period.

She’d been irritable for a few days-if a person who almost never communicated could be called irritable-she didn’t want to be held or kissed. She slapped Theo across the face while they were making love. She pretended like it was an act of passion, except that it hurt, and tears came to Theo’s eyes. When it was over, he said, “Why did you hit me?”

She rolled away from him on the mattress. “Sorry, I was letting out some frustrations.”

“What kind of frustrations?” This was what ate away at him: Antoinette had frustrations and he didn’t even know about it. “Frustrations with me?”

She stood up and looked him over.

“I missed my period.”

“Oh, shit,” he said. They had never used condoms because Theo figured Antoinette would take care of herself-the pill, IUD, menopause for all he knew. “So you think you’re pregnant, then?”

“Well, it’s been a while, but it feels the same.”

“Wait a minute. What feels the same? You’ve been pregnant before?”

“I have a daughter,” Antoinette said. “Or I had a daughter. Twenty years ago.”

“You’re kidding,” Theo said. “You have-a daughter who’s older than me?”

“I gave her up for adoption,” Antoinette said.

“Really?” Theo said. “How come?”

She sighed. “It’s a long story.”

“Tell me,” Theo said. “You never tell me anything.” He touched his cheek where she’d hit him and wondered if she’d left a mark.

She sat down on the edge of the bed and gazed out the window into the woods. “Let me ask you a question,” she said. “Why would you want to know about an old woman’s life? What could it possibly mean to you?”

“I want to know you, Antoinette,” Theo said. “I show up here every day and we… we screw and I don’t know the first thing about you. I don’t know anything about your family, your parents, this daughter. Just tell me about the daughter, okay?”

“It’s old stuff,” Antoinette said. “Old and sad.”

“Please,” Theo said.

“You’re going to be shocked,” she said.

“I won’t be shocked,” he said, although he felt completely shocked-Antoinette thought she was pregnant, and she’d been pregnant before. “I promise.”

Antoinette wound a strand of black hair around her finger. “I got married right out of college,” she said. “My husband and I lived in Manhattan, and my husband was a consultant for Price water house. He had projects in California, so he was away a lot, but that didn’t bother me. I was getting my master’s in dance at NYU, I had a great apartment on the Upper East Side to decorate, I was busy exploring the city. Then, after a year or so, I discovered I was pregnant.”

“Okay,” Theo said.

“I was a twenty-three-year-old dancer whose husband was all but living on the West Coast. There was no place in my life at that time for a child. I wanted to terminate the pregnancy.”

“Get an abortion?” Theo said.

“Get an abortion. But my husband talked me out of it. He wanted the baby. It’s going to be great!’ he said. “We’re starting a family!’ He convinced me to leave school, which I did, and in return I asked him to leave the project in California and take a project closer to home. So he did. He took a project in Philadelphia and he was less than two hours away by train. He was home every weekend. He walked with me in Central Park, he took me to see Aida at the Met, he went out in the middle of the night to get me watermelon from the Korean deli.” Antoinette tightened her fists and brought them to her ears, like she was trying to block out an awful sound.

“Then what happened?” Theo asked. Here was Antoinette’s history, her real history, that even his mother might not know.

“One day when I was pretty far along, seven months or so, I found myself down at Penn Station, and I decided to surprise him. I got on the Metroliner and walked from the train station to his hotel. The front desk clerk knew I was his pregnant wife. He gave me a key to his room; he was happy to do it.”

Theo felt like he was standing on a cliff where he was drawn to the edge, yet afraid of falling. “And?” he said.

“And I walked in on him having sex with two women. Monica, who was his consulting partner and another woman, their client. The three of them were so… involved with each other, they didn’t even notice me standing there until finally I thought to scream. They all noticed that.”

Antoinette was openly weeping, wandering the room like she was looking for something. A tissue, maybe. She disappeared into the bathroom and emerged with a hand towel.

“His name was Darren.” Antoinette blew her nose into the towel. “I haven’t spoken that name in over twenty years. Darren Riley.”

“You still use his last name,” Theo said.

“I loved my husband. I loved him desperately. He was one of those special people who everybody loves-men, women, dogs, babies. He was charming, dynamic, funny. And that was his downfall. Women fell over themselves for him, they allowed themselves to be degraded. Monica later told me that there had been other threesomes, in other cities, in California, and before that, even.”

Theo thought he might vomit. He grabbed a pillow and pressed it to his crotch. “What did you do?” he asked.

“I went back to New York, alone. Darren didn’t bother trying to get me back. I guess he knew he blew it. He gave me a quick divorce and lots of money. But it was like he didn’t even try. He didn’t apologize, and suddenly it seemed he didn’t want the baby after all. When she was born, I couldn’t make myself feel anything but anger. I couldn’t feel any love for her; I couldn’t even give her a name.”

“So what happened?”

“I tried to kill myself. I took pills. My neighbor found me unconscious, the baby screaming in her crib. I hadn’t fed her in, like, twelve hours. Social services took the baby away and by the time I was released from the hospital I realized I couldn’t raise her. I didn’t want to raise her.” Antoinette pressed her thumb and forefinger to the bridge of her nose and threw the towel into the corner of the room. “What has stayed with me after so many years is how Darren made me love that child and then he stole that love away. It is the cruelest thing I’ve ever known anyone to do.” After a few seconds, Antoinette straightened into perfect posture. “After the baby was gone, I moved away and started over.”

“You came here?” Theo said.

“I constructed a life that allowed me to survive day to day. Minimal interaction, no one to care about but myself. Here in the woods on this island thirty miles out to sea. This is it, Theo. This is my life.”

She retreated into the bathroom. Theo dressed quietly; it was past time for him to go, but he couldn’t bring himself to leave. No information for months, and now a deluge.

“So now you think you’re pregnant again?”

She stood with her hands on either side of the sink, staring into the mirror. She nodded.

Here was the one thing that Theo had been afraid of ever since he knew enough to be afraid of it, and now he wasn’t afraid at all, he was excited. Thrilled. Antoinette, pregnant.

“It’s okay,” he said. “If you’re pregnant, it’s okay.”

“It’s anything but okay,” Antoinette said. “God is punishing me.”

“For what?”

“For you,” Antoinette said. “For sleeping with an eighteen-year-old.”

“I want to have a baby with you,” Theo said.

“No, you don’t. We’ll do what’s easiest for both of us. If I’m pregnant, I’ll have an abortion.”

“But I love you! I’ve been trying to tell you I love you for weeks, but it’s like you don’t hear me.”

“I hear you,” she said.

“But you don’t believe me.”

“I believe you,” she said.

“But you don’t love me back.”

“There’s no way to make you understand. You’re too young. And so you’re just going to have to trust me, Theo.” She walked toward him and took hold of his face, her hand resting exactly on the spot where she had slapped him, only now she was gentle, as gentle as if he were a baby himself, and he saw that her eyes were filled with something, and he let himself believe that it might be love.

There was a day or two of reflection. Theo marveled at the power of his own body; he’d created another human being. He ran through scheme after scheme, one more unlikely than the next. He and Antoinette marrying, raising the child. Theo would graduate from high school in a year. He would forgo college and work for his father. Or, if his parents disowned him, he and Antoinette and the baby would move off-island. To California. France. South Africa.

In the evenings, Theo tried to get Antoinette to talk about her past some more, but she wouldn’t. Sometimes she was upbeat, and when he arrived she’d be sitting on the built-in benches of her deck with a glass of chardonnay and a book. Other days he found her in the bedroom with the shades drawn, and when he knocked on the door or tousled her hair, she opened one eye and murmured, “Go away, Theo. Go home to your mother.”

Then, on the first of August, a day when his job at the airport had been particularly hellish-all the July people leaving, the August people arriving- she showed him the pregnancy test. It was one of the evenings when she was out on the deck. She poured him a glass of wine, and they sat quietly listening to the birds in the surrounding trees, and then she went into the bedroom and came back with a white plastic stick with two purple stripes. Antoinette held it out to him, turning it in the fading light as though he might want to inspect its authenticity.

“Well,” he said. “Now what?”

“I’ve made an appointment off-island for the Tuesday after Labor Day,” she said. “An appointment for an abortion. That gives me four weeks to think it over.”

“Don’t have an abortion,” Theo said. “Please.”

“I don’t see any options,” Antoinette said. “You, my dear, are in no position to think about being a father. Not at eighteen.”

He no longer felt eighteen, and he said so.

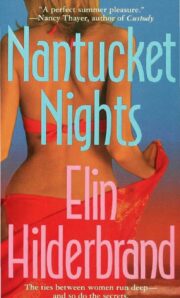

"Nantucket Nights" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Nantucket Nights". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Nantucket Nights" друзьям в соцсетях.