Thinking about Raoul was even more painful. In the nineteen years of their marriage, Kayla and Raoul had only spent a handful of nights apart-the nights Kayla had slept on the beach at Great Point for Night Swimmers. Saying good-bye was difficult: Raoul took her to the airport while the kids were at school, so it was just the two of them in the near-empty terminal. Kayla had never said good-bye to Raoul before, and she didn’t know how to act. Raoul tried to make light of her leaving by humming “Leaving on a Jet Plane,” and when Kayla grew angry at him for this-saying he couldn’t carry a tune, so please save her ears-Raoul grew angry at her. They’d ended up sitting side by side, arms crossed, staring at the woman who worked the Cape Air counter as she helped another customer with a fouled-up ticket. Then, when Kayla’s plane was called, Raoul took her elbow and walked her to the gate and kissed her as sweetly as he had ever kissed her, and Kayla cried.

Kayla missed the sound of Raoul’s voice, the feel of his scruffy face when he didn’t shave for a day or two, the way he touched her in the middle of the night as if making sure she was still there. She missed hearing him talk to the kids, she missed his smell of fresh lumber and plaster and paint, she missed pulling crumpled pink receipts from Marine Home Center out of his pockets when she put his clothes into the hamper at night. But she hadn’t been a good wife. She’d suspected him of adultery for years-she admitted this now-and so she harbored old anger about being deceived along with this new anger about being deceived. And then Jacob. God, Jacob. Every minute of this vacation was a struggle not to fall into a pit of self-loathing.

While there was a chance that her marriage would survive, Kayla understood that her friendships with Val and Antoinette were over. Val had turned Kayla in to the police, and Kayla slept with Jacob. Both actions were unthinkable. Or rather, what was unthinkable was that after twenty years a friendship as strong as theirs could be so violently destroyed. Tom apart in a matter of twenty-four hours. Kayla had packed up all of Val’s things and sent Theo to drop them off at her house.

At the end of her evening swim, as Kayla climbed out of the water, dried off, and walked back to her unit, she asked the question that became her mantra, her raison d’etre: What had happened to Antoinette?Was she alive? Dead? Here, Kayla was flummoxed. She’d asked Raoul to leave a message at the office of Mary Lee’s as soon as a body was found, but she’d heard nothing. And as far as she knew, the police were conducting what they called a limited missing-persons investigation, but again, she’d had no news. Everyone thought, or had grown to accept, that Antoinette drowned during Night Swimmers. She’d been drinking, true; the water was tricky, the riptide fierce and unpredictable. But something nagged at Kayla, and that something was Antoinette herself. She was too capable, too strong, too clever to let herself get swept away. It sounded stupid, but it wasn’t Antoinette’s style. She was a survivor. So where was she? Hanging out with the Jim Morrison groupies at Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris, or trekking on the back of an elephant in the teak forests of northern Thailand? Mostly, Kayla thought of Antoinette as vanished. Not alive, not dead, just gone. Meaning, she could turn up again somewhere. Resurface.

Kayla had been dreading this vacation from the beginning, and yet, when the six weeks were over, she panicked at the thought of returning to Nantucket. She thought back to the words she once heard Antoinette say: “I’m lonely all the time, every day. But there are far worse things than being lonely. Like being betrayed.”

Kayla didn’t want to relinquish her solitude, her simple routine, her ocean view or her solitary night swims. She thought brashly of writing a forbidden postcard, Decided to stay here for the rest of my life. Love, Kayla.

She returned on the sixth of November, and as her plane flew over the island, Kayla was filled with trepidation. The first landmark she spotted was Great Point lighthouse, which from the plane looked like nothing more than a white stake planted in the ground. A stake marking the site of her sadness. Then Kayla took in the cranberry color of the moors, the dark blue ponds, the amber and green plots of Bartlett’s farm. Autumn had come while she was away.

She didn’t know what to expect when she entered the airport. She almost walked past Raoul-he was sitting on a bench reading the newspaper-but he reached out and caught the skirt of her dress. He looked the same, the most beautiful man she had ever known, but his face had changed, too. He looked sad; he looked scared. Both her fault.

She didn’t cry. She just stood and ate him up with her eyes, and when he said, “Do you need help with your bags?” she let him come to her rescue.

Kayla stifled all the questions that had been running through her mind for the previous six weeks: Do you still love me, can we make this work, will you ever trust me again? She reminded herself that Raoul was a builder; he believed in process. The relationship would have to be restored one brick at a time. There was no quick fix, and there were no easy answers.

Still, she felt she had to be the first to say something. As they stood at the baggage claim waiting for her suitcase, she spoke up. “I missed you.”

“Oh, yeah?” he said.

She swallowed. “Yeah. Did you miss me?”

He turned and took her in his arms, and she pressed her face into the side of his neck and wondered how she’d made it through six weeks without him.

“Oh, yeah,” he said.

By Thanksgiving, things appeared, on the outside, to be back to normal. Kayla ventured out of the house again, although she spoke to no one about what had happened Labor Day weekend. When people asked about Theo, she told them he was attending Boston Hill to improve his chances of getting into a good college.

Raoul went to court and was fined five hundred dollars and sentenced to fifty hours of community service. He offered to build a new jungle gym for the elementary school playground, and he let Luke help him design it. He and his crew started work on a house on Eel Point Road. The client bought the sixty-five-acre parcel of land for almost twenty million dollars and he told Raoul he wanted a house that would make the Tings’ look like a scallop shanty.

The kids-Jennifer, Cassidy B., and Luke-still didn’t know the whole story. They became absorbed with school and friends and pretended to forget all about it.

Raoul and Kayla called Sabrina to find out how Theo was doing. He was hurt, Sabrina said, but healing. Kayla wanted to talk to him, she wanted to see him, but he wasn’t ready. He needed space, he needed time. Kayla, more than anyone else in the family, understood.

In the Inquirer and Mirror in the middle of November, Kayla saw that John and Val’s house had sold for over a million dollars. A few weeks later, the Nantucket Bar Association placed an ad wishing Valerie Gluckstern “lots of luck in her new practice in Annapolis, Maryland.” Kayla felt a sense of loss, but more than anything, she was relieved.

On the outside, everything appeared to be back to normal.

And then, December. The day that Kayla went Christmas shopping in town, the day when everything seemed so festive, so right. The day the phone call came that nearly stopped her heart.

“Kayla,” the voice on die answering machine said. “This is Paul Henry. I have news. Please call me.”

I have news. Kayla walked aimlessly through the house, trying to control her breathing. She entered Theo’s room. It was pristine-dusted, vacuumed, bed made. The way Kayla always imagined it would look once Theo went to college, until she and Raoul bought a large piece of exercise equipment, or decided to redecorate and make it a guest room.

I have news.

What was she afraid of? The reality of Antoinette’s death-perhaps even the physical reality of it, the remains of Antoinette’s body. What would that look like now, after so many months? A skeleton? A blue, bloated corpse? Once Kayla saw the body, the body that contained her grandchild, it would haunt her forever. She would see it in her sleep, she would become afraid of the dark. The finality of it: a dead body. Not to mention the possible criminal charges, the word murder silently attached to Kayla’s name. Or not so silently: If the detective drummed up enough evidence, there would be an indictment, a trial.

I can’t do it, she thought, longing for her one-bedroom unit at Mary Lee’s by the Sea. I can’t call him back.

What was more terrifying was the thought that Antoinette might be alive.

She tried to forget about the message. After all, it was Christmastime. Kayla convinced Raoul to take the next day off of work and they flew to the Cape to do some Christmas shopping while the kids were in school. They bought Luke a North Face jacket and a Razor scooter, Cassidy B. a complete set of grown-up art supplies: oil paints, watercolors, pastels, charcoal pencils, sculpting clay. They bought Jennifer a leather skirt and Rollerblades. They bought Theo a computer and arranged to have it sent to Boston. Then, exhausted, they ate lunch in the noisy, crowded food court, where kids too young for school screamed and smashed French fries into their hair.

There, amid the din, Kayla heard Paul Henry’s voice. I have news.

Kayla listened to the piped-in Christmas music, Karen Carpenter singing, “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas.” She wanted to disappear into the glitter and tinsel and spun sugar of Christmas at the Cape Cod Mall. Forget about drownings and love affairs and detectives. But the specter of Paul Henry crunched into her Christmas spirit like the Grinch. Kayla tried to smile at Raoul across the dinky Formica table.

“Is something wrong?” he asked her. “You seem preoccupied.”

“I have to make a phone call,” she said. “Where are the pay phones?”

“Who do you have to call?” Raoul asked.

“Your mother,” Kayla lied. “There was something else she said Theo wanted, something for school, but I can’t remember what.”

Raoul nodded and Kayla ran around the perimeter of the food court until she found the corridor with the rest rooms and the pay phones.

“Come in,” Paul Henry said.

“I can’t,” Kayla said. “I’m in Hyannis. Christmas shopping. Just tell me what the news is, Paul. Did you find a body?”

“I’ll tell you when you come in,” he said. “This isn’t something I’m willing to tell you over the phone. Tomorrow morning?”

“Fine,” Kayla said. She slammed down the phone.

“What did mom say?” Raoul asked when she returned. He was busy finishing her chicken teriyaki and didn’t notice her agitation.

“Sabrina wasn’t home,” Kayla said.

“Probably out shopping for dinner,” Raoul said.

The police station was decorated for Christmas-a row of garlands across the front desk, blinking white lights in the window. The officer behind the glass shield was wearing a Santa hat. He took one look at Kayla and picked up a phone. Paul Henry emerged from the hallway ten seconds later. He reached for Kayla’s hand and, incredibly, kissed her on the cheek. Kayla hadn’t slept at all the night before. She lay next to Raoul counting his breaths, imagining possible scenarios. Kayla realized she was grateful for one reason. She wanted an end; as gruesome or as scary as it might be, she wanted closure.

She followed Paul Henry down the dim hallway to his office. Paul Henry sat down behind a kidney-shaped desk. Kayla collapsed in a needlepoint chair while Paul Henry opened a manila file folder. He read. Kayla studied the photographs on his desk- his wife, Carla, their kids, a grandchild. Kayla studied his hands-he wore a gold wedding band. Raoul never wore his wedding ring because when he built houses it could catch on something. Instead, he kept it in a plain white box in his sock drawer. A lonely gold band with her name inscribed inside and their wedding date, June 1, 1981.

Kayla looked expectantly at Paul Henry.

“I have to tell you, Kayla, I called the woman’s daughter yesterday. Told her who I was. She hung up on me, and I haven’t had any luck reaching her again.”

“Okay.”

Paul Henry took a small notepad and copied something from the file. Like a doctor writing down the diagnosis of a terminal disease, Kayla thought. He slid the paper across the desk. Kayla was afraid to look at it. “Can’t you just tell me?”

Paul Henry put down his pen. “Ms. Riley is living on Martha’s Vineyard.”

“She’s alive?” Kayla’s stomach dropped; she started to sweat. “For the love of God, Paul, she’s alive? Living on the Vineyard? Are you sure?”

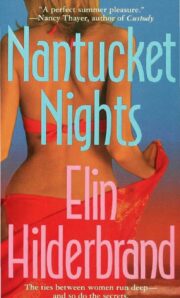

"Nantucket Nights" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Nantucket Nights". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Nantucket Nights" друзьям в соцсетях.