There was worse to come. While the two guards immobilized him, Gaspard began whipping Grey’s back. Dimly Grey realized that the leather streamers on the cane were the lashes of a whip and the cane itself was the handle.

After a dozen or two agonizing blows, Grey sagged to the floor between the guards. “Let him fall,” Gaspard said contemptuously. “Remove the shackles. They aren’t needed. There is no way the goddam will escape this cell.”

Grey lay on the floor, barely aware of a key unlocking his wrist manacles. The guards rose and followed Gaspard as the jailer limped from the cell, his wooden leg tapping ominously. They took the torch with them.

After the heavy door was closed and locked, Grey was left in darkness. Even the sliver of light at the bottom of the door disappeared as his jailers walked away.

Grey felt panic rising at the thought of being trapped in darkness until he died screaming. What did the French call the ultimate prison, a oubliette? But that was a pit, wasn’t it, with the prisoner at the bottom of a deep shaft? The name meant forgotten, for prisoners were forgotten and left to die.

He had the mad thought that the guillotine might be better. At least death took place in open air and was quick, if ugly.

But he wasn’t dead yet. Now that he was free of gag, blindfold, and chains, he could breathe and move freely. As for the darkness—it hadn’t destroyed him on the endless journey to this place, and he wouldn’t let it destroy him just yet.

He pushed himself up on his knees and fumbled for his shirt and coat, which had been dropped nearby. The heavy fabric inflicted a fresh wave of pain on his lacerated back, but he needed protection against the biting chill.

Then he listened. Absolute silence except for the faint sound of trickling water somewhere quite close. Given the dampness around him, that was unsurprising.

What had he seen of his cell before Gaspard left? Stone walls, stone floor, damp and solid. The room wasn’t huge, but it wasn’t tiny, either. Perhaps eight paces square, with a very high ceiling. There was something in a corner to his left. A pallet, perhaps?

Swaying, he got to his feet, then moved to his left with his arms outstretched to prevent collision. He still managed to sideswipe a wall by coming at it from an angle, but a few more bruises made no difference.

He stumbled on something soft. Kneeling, he explored by touch and found a pallet of straw and a pair of coarse blankets. Luxury compared to what he’d endured since his capture.

Standing, he skimmed one hand along the wall so he could discover the dimensions of his cell. Down the side wall to the back, opposite the door. He turned and moved along the back wall. About what he estimated as the midpoint of the wall, he stumbled on a rocky obstacle and fell heavily.

More bruises, damned painful ones, but nothing broken, he decided after he recovered his breath and tested the new injuries. He explored with his hands and identified two irregular blocks of stone.

One was chair height, so he hauled himself up and sat, though he couldn’t lean against the wall because of his injured back. As the throbbing in his knees faded, he realized he had never properly appreciated the convenience of chairs before.

The second block of stone was about a foot and a half away, roughly rectangular, and around table height. He felt positively civilized.

After the pain diminished, he resumed his exploration, moving even more slowly. At the far corner, he felt a film of water seeping down the stones. It wasn’t a lot, but perhaps enough to keep him from dying of thirst if other drink wasn’t offered.

There were no more stone blocks. The only other feature he located was the massive wooden door and its frame. He circled again even more slowly. This time in the back corner where the moisture dripped down, he sensed the movement of air. He knelt and found a hole about the size of two fists. The water dripped down into it and there was a faint scent of human waste.

So this is where prisoners relieved themselves. It could have been worse. He used the facilities, then made his way back to the pallet, and wrapped himself in the blankets, lying on his side to protect his back.

Despite his exhaustion, he found himself staring into the darkness wondering what lay ahead. Durand’s comment that it no longer mattered what the English thought suggested that the war was about to resume after a year of truce.

Grey wasn’t surprised to know that. He’d seen suggestions that the French were using the truce to regroup for another round of conquest. Since he had joined the rush of Britons to Paris when the truce began, his friend Kirkland had asked him to keep his eyes open and pass on what he saw.

Grey had used that as an excuse to seduce a married woman, and that action had brought him here. Not that Camille had required much seduction. Looking back, he wasn’t sure who had seduced whom.

Dear God, what would become of him? Might Durand offer him for ransom? His parents would pay anything to get him back. But Durand wanted him to suffer. That could mean being imprisoned forever here in the darkness.

Not forever. Until he died. How long would it be until he’d be praying for death? The knowledge that he was likely to die here in the darkness, alone and unmourned, made his heart hammer with panic. Grimly he fought the fear.

Breaking down shouldn’t matter since no one was here to sneer at his weakness. But it mattered to him. Everything in his life had come easily, and even when caught in mischief, he’d suffered few consequences. Until now. Resigning himself to living in darkness, he wrestled his demons until fear faded and he slept like the dead.

The next morning he awoke to find light entering his cell from a horizontal slit window near the high ceiling of the cell.

For that beautiful sight, he wept.

Chapter 5

France, 1813

In the late afternoon sun, the village of St. Just du Sarthe looked much like any other village in northern France, apart from the medieval castle rising above. As Cassie drove her cart over the hill opposite the castle, she paused to study her goal.

Locating Durand’s family seat hadn’t been difficult. She’d been fortunate that dry, cold weather had saved her from becoming bogged down in snow or mud. She’d moved at a leisurely speed, stopping in villages to sell her ribbons and buttons and bits of lace, along with Kiri’s perfumes and a few remedies.

She’d bought as well as sold, acquiring items of clothing or handicrafts that could be sold elsewhere. In short, she’d behaved exactly as a peddler should.

Snapping the reins over the back of her sturdy pony, she made her way into the village. It was large enough to have a small tavern, La Liberté. Cassie halted there, hoping to find both hot food and information inside.

The taproom was empty except for three ancient men sipping wine together in one corner. A robust woman of middle years was busy behind the bar, but she glanced up with interest when Cassie entered. A female stranger traveling alone wouldn’t be common here, and Cassie was moving with the deliberation of an older woman.

“Bonjour, madame,” Cassie said. “I am Madame Renard and I hope I may find some hot food and a room for the night.”

“You’ve come to the right place.” The woman chuckled. “The only place. I’m Madame Leroux, the landlady, and I’ve a plain room and some hearty mutton stew and fresh bread if you’re interested.”

“That and a glass of red wine will suit me well.” Cassie guessed that the landlady would be a good source of information. “I’ll settle my pony in your stable first.”

Madame Leroux nodded. “The food will be ready when you return.”

The pony was as happy to be indoors and fed as Cassie was. She returned to the taproom and settled into a chair by the fire, grateful for the warmth.

She was removing her cloak when the landlady emerged from the kitchen with a tray containing stew, bread, cheese, and wine. Cassie said, “I thank you, madame. Will you join me in a glass of wine? I’m a traveler in ladies’ notions, and I’m sure you will know if there might be local interest in my goods.”

“Merci.” Madame Leroux poured a glass of wine and settled comfortably on the other side of the fire. Expression curious, she asked, “Isn’t it dangerous to travel alone?”

Besides moving slowly, Cassie had grayed her hair and was wearing the Antiquity scent, so she must seem worrisomely fragile. “I’m careful, and I’ve not had trouble.”

“What do you sell?”

Cassie listed her wares between mouthfuls of the excellent stew. When she finished, the landlady said, “Our weekly village market is tomorrow. In midwinter, new goods will be welcome. I think you will find it worth your while.”

Cassie sipped at her wine. “What about the castle above the town? Might I find customers there? I have some truly fine perfumes blended by a Hindu princess.”

The other woman smiled appreciatively. “An intriguing description, but Castle Durand is a quiet place. The master visits very seldom, and his wife even less. There are never guests unless you count a prisoner or two in the dungeon, and I doubt they have the coin to buy.”

“A dungeon?” Cassie looked properly shocked. “In modern France?”

“Men with power don’t give it up easily,” the landlady said cynically. “The Durands have been lords of the castle forever. They’re called the Wolves of Durand. The last Durand got chopped for being an aristo, but there’s a Durand cousin up there now, not much different from the last one apart from calling himself Citoyen instead of Monsieur le Comte. ’Tis said this Durand has an English lord locked in the dungeon, but I have my doubts. Where would he find an English lord?”

“That seems unlikely,” Cassie agreed, concealing her excitement. “Surely there are female servants? After the market, I could drive up there to show my wares.”

“Go at your peril,” Madame Leroux said. “Half the village is ill with influenza—that’s why I’m so quiet here. I hear that most of the castle staff is ill, too. Not the sort of thing that usually kills, but it creates plenty of misery. Best stay away.”

“I may have something for that,” Cassie said. “The Hindu woman who made the perfumes also gave me what she called thieves’ oil. The legend is that during the plague years, thieves used it to stay safe when they robbed the dead. I have tested it myself on this journey, and I haven’t become ill despite the weather.”

The landlady’s gaze sharpened. “I might be interested in that myself.”

Cassie dug into her bag for a sample. “Try this. A few drops in your palm, rub your hands together, then cup them and sniff the scent.”

Madame Leroux followed the instructions, her nostrils flaring as she sniffed the pungent mixture. “Smells like it ought to do something! Does this remedy really work?”

“As one businesswoman to another, I will admit that I’m not sure,” Cassie replied. “But I haven’t had so much as a cough since I started using it.”

Madame Leroux took another sniff. “Perhaps we can trade your oil for my lodging?”

After a brisk bargaining session, agreement was reached and Cassie handed over a larger bottle of thieves’ oil. Madame Leroux chuckled. “If you call at the castle and fall ill with the influenza, at least you’ll know it’s no good.”

“I hope it works,” Cassie said with an answering smile. She now had a good reason to go to the castle, where she could learn if Kirkland’s long-lost friend was really in Durand’s dungeon. “But perhaps I will head on to the next village. This country is new to me. How far to the next village that has lodgings? In summer, I am happy to camp out with my pony, but not in February!”

“Three to four hours’ drive if the weather stays clear.”

“Then I shall move on after the market.” Cassie mopped up the last of the stew with the heel of her bread. “But I shall make sure to stay here if I come this way again.”

Chapter 6

Castle Durand, Summer 1803

By morning’s light Grey saw that the heavy door to his cell had two small trap doors opened from the outside, one at head height, the other near the bottom. “Breakfast, yer lordship,” a sneering voice said as half a loaf of bread and a tankard of tepid minty tea was placed through the lower door. “Return the tankard later or no dinner for you.”

Because he was hungry, he obeyed. The breakfasts were usually bread with drippings smeared on and more of the herb tea. No costly China tea for prisoners.

Dinners were sparse but more varied. There might be a bowl of stew, or perhaps vegetables and a bone with meat on it. Occasionally a boiled egg. The best part was the pewter goblet of wine. It was always a coarse young table wine, but it gave him something to look forward to. He felt occasional fleeting amusement that because this was France, prison food wasn’t quite as dreadful as it might have been.

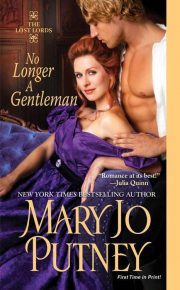

"No Longer a Gentleman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "No Longer a Gentleman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "No Longer a Gentleman" друзьям в соцсетях.