James Morland had carved out a niche in immigration and human rights law in his chambers in York. He’d fallen in love with one of his clients, a Somali woman who had just opened a restaurant near the university that was already winning rave reviews. James had gained both happiness and half a stone in the process.

Bella Thorpe had featured briefly in a reality TV show but had been eliminated in the first public vote of the season. Her brother Johnny had been fired by his bank after a series of dubious transactions came to light. Susie Allen took great delight in reporting their misfortunes to the Morlands, and even the vicar could not avoid the sin of schadenfreude.

And what of General Tilney? His first reaction to the rebellion of his younger children was to cut off their allowances and bar them from Northanger Abbey. His capacity for cutting off his nose was remarkable, but he had reckoned without the compassion their mother had installed in Henry and Ellie. A year after the terrible night when he had cast Cat out of the abbey, his younger son arrived there, having colluded with Mrs Calman to ensure the General was home alone.

Henry never revealed what had passed between them, but although there was never much subsequent warmth between father and son, neither was there the bitterness there had been previously. Ellie too had been welcomed back into the fold; now she had completed her degree, she was to take up residence at Woodston, where her father had promised to build a studio at the water’s edge.

The moral or message of this story is hard to discern. And that is as it should be, for as Catherine Morland found out to her cost, it is not the function of fiction to offer lessons in life.

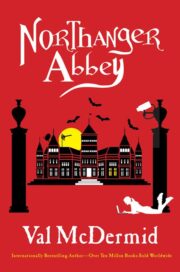

"Northanger Abbey" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Northanger Abbey". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Northanger Abbey" друзьям в соцсетях.