But suddenly he lifted his head and his arms about her stiffened. He held his head in a listening attitude. Even in the darkness she could see the frown on his face.

Lily was never sure afterward if she heard a sound herself—a sound other than the distant noise of revelry. But certainly she was suddenly awash in that terrible dread again as he turned away from her to gaze into the trees at the other side of the path. She was not even sure afterward if she saw anything. She was not quite sure she had seen a figure in a dark cloak with a pointed pistol. Everything happened too fast.

Neville suddenly spun back toward her and whisked her around behind the tree, his own body between her and danger. The sound seemed to come after. The bullet had missed her, she thought as he pressed her painfully against the other side of the tree, his back against her, shielding her. But the noise of it still rang in her ears.

She felt suffocated. His hands were spread behind him, on either side of her body. She could scarcely breathe. Even so she welcomed the shield he had provided for her. Without it, she would disintegrate into mindless terror.

She could hear him breathing in heavy gasps that she knew he was trying to silence so that he would not betray their whereabouts. And she knew that she was an impediment to him. Without the necessity of protecting her, he could move, go in search of their assailant instead of waiting for him to find them.

It seemed that they stood there in unbearable tension for five minutes, even ten—probably, she thought afterward, it had been no longer than a minute or two. And then there was the sound of laughter fairly close and drawing closer and she knew with knee-weakening relief that someone was coming along the path—more than one person, in fact.

Actually it was four. As they came up to the tree and then passed it, Neville took her firmly by the hand and drew her out onto the path. They walked down it behind the two couples, who were so merrily foxed that they did not appear to notice that their numbers had been swelled.

"I am taking you back to Elizabeth," Neville said, setting one arm about her when they reached the main avenue. "And then I am going back to find the bast—" He cut off the word in time. He was breathing noisily.

But Lily, setting an arm firmly about his waist, fearing that she would collapse, suddenly became aware of something—something warm and wet and sticky.

"You have been hit," she said. And then in utter panic: "Neville, you have been shot!"

"It is nothing," he said through teeth she knew he had gritted together. And he increased their pace.

But as they approached the box, he released his hold on her and half pushed her into a startled Elizabeth, who was standing outside the box with the Duke of Portfrey.

"Take her," Neville said harshly. "Get her out of here. Take her home."

And he collapsed on the ground at their feet.

Chapter 22

He knew from past experience what was happening.

"The devil!" It was Joseph's voice—he was hanging on to the right wrist with a grip of steel. "You could not have slept a few minutes longer, Nev? Enjoyed dreamland and all that?"

"You can let go your infernal grip on me," Neville said. "I am not going to struggle. Who is the sawbones?"

"Dr. Nightingale is my personal physician, Neville." Elizabeth's voice, as he might have expected, was cool and sensible—no hysterics from her. "The bullet is still in your shoulder."

And Dr. Nightingale had already made a pass at removing it. That was what had brought him to, Neville realized, taking a firm grip on the edges of the mattress. He opened his eyes at the same moment. His head was turned to the left—it was Lily who was clinging to his left wrist.

"Get out of here," he told her.

"No."

"Wives are supposed to obey their husbands," he said.

"You are not my husband."

"And of course," he said, "you have seen far worse than this on the battlefield. This is nothing at all to you. Foolish of me to try to protect you from a massive fit of the vapors."

"Yes," she agreed.

The physician, far less deft at such a task than the army surgeons, came at him again then, trying to probe gently and causing prolonged and excruciating agony. Neville kept his eyes on Lily's until the pain threatened to get beyond him, and then he clenched his eyes shut and gritted his teeth hard.

"Ah," Dr. Nightingale said at last, a note of satisfaction in the sound.

"Got it!" Joseph sounded breathless, as if he had just run a mile with a wild bull in hot pursuit. "It is out, Nev."

"And no damage to the bone or sinews from what I can see," the doctor added. "We will have you patched up in no time, my lord."

The pain did not subside to any substantial degree. He felt submerged in it, peering out at reality from a long distance within it. But he knew as he opened his eyes again that Lily's hand had gone from his wrist and was somehow clasped in his own—crushed in his own. For a few moments longer his hand seemed locked in place, but gradually he relaxed it and set hers free. He saw with a curious detachment from deep inside himself that her fingers appeared white and tightly welded together, that for a short while she could neither move nor separate them. It was amazing he had not broken all of them, but she had not made a sound.

She turned away and then back again and he felt a cool, damp cloth against his hot face.

Joe was talking—Neville did not know what about. The doctor was still busy with his shoulder and apparently Elizabeth was assisting him. Neville watched Lily as she worked quietly and efficiently, as she had always done after a battle or skirmish, dipping the cloth, squeezing out the excess water, pressing it lightly to his face or his neck. He made a cocoon of his pain and hid deep inside it.

"Was he caught?" he asked finally. He had suddenly remembered being at Vauxhall, kissing Lily in one of the darker alleys, considering the very indiscreet act of moving her back father into the trees so that they could take their embrace farther, and then recognizing the strange prickling feeling along his spine as the type of sixth-sense warning of danger he had developed during his years as an officer. He had heard the snapping of a twig, perhaps, without even realizing it. He remembered seeing a cloaked figure lurking in the trees at the other side of the path, aiming a pistol at them. He remembered leaping sideways to shield Lily and taking the bullet that would surely have killed her. "Did someone catch the bastard?" He remembered Elizabeth's and Lily's presence too late.

"Harris and Portfrey went charging off in pursuit," the marquess said, "as did a small army of other men, Nev. I would wager Vauxhall emptied out faster of ladies and everyone else than in its whole history. I doubt anyone found the gunman, though. A man in a dark cloak, Lily said. There were probably fifty men there to answer the description, Portfrey and myself among them."

"You were in the wrong place at the wrong time, Neville," Elizabeth said coolly. "There, Dr. Nightingale is finished. Perhaps you would see him on his way, Lily, while Joseph and I get Neville out of the rest of his clothes and into a nightshirt."

"No," Lily said, "I am staying."

"Lily, my dear—"

"I am staying," she said.

Neville gathered that it was Elizabeth who saw the physician out. For him there followed a nightmarish few minutes—which felt more like a few hours—while Lily and his cousin undressed him and somehow got him, wounded shoulder and all, inside someone's nightshirt, and hauled him off the bed so that the towels on which he had been lying could be removed and the bedclothes properly turned back. Then there was all the difficulty of lying down again. He had suffered his share of wounds during his war years. Every time he found that he had not quite remembered the full extent of the physical agony.

He could hear the rasping of his own breathing. If he concentrated on the rhythm of it, he thought, he could impose some sort of control over the situation.

"We should not have put him on his back." That was Joseph.

"No." That was Lily. "He will be better thus. Neville, you must take this laudanum that the doctor left."

"Go to hell," he said, and his eyes snapped open. "I do beg your pardon."

Her lips were quirking into a smile. "I will support your head," she said.

He had always fought against taking medicines of any sort. But he meekly downed the whole dose of laudanum as punishment for what he had said to her.

After that everything became a blur of pain and gradual, blessed fuzziness. He thought Elizabeth and Portfrey were in the room, though he did not open his eyes to see or take any particular notice of the report that no trace had been found of any suspicious character with a pistol. And then there were just Elizabeth and Lily in the room, arguing over who would stay with him during the night. At least, Elizabeth was arguing—she would take the first watch, the housekeeper the second. It was unseemly for Lily to be alone with him in his bedchamber—if only he could climb out of the depths of himself, he would find something decidedly funny in that argument. She would tire herself out. She was too emotionally involved to make a good nurse—they could expect a fever, and then calmness and a certain detachment would be essential.

Lily put up no argument at all; she simply refused to leave.

He was sinking fast into lethargy by the time they were alone together, but he opened his eyes to confirm his impression that they were. She was standing beside the bed, gazing down at him. She was still wearing the elegant gold silk and gauze evening dress she had worn to Vauxhall.

"You are not going to sit beside the bed all night while I sleep," he told her—it sounded to his own ears as if his words were slurring. "If you are intending to stay, take off that dress and lie down beside me. You are my wife, after all."

"Yes," she said, but his mind was not focused enough to understand to what she was agreeing.

The pain had localized and became a dull pulsing in his shoulder. His tongue felt thick. His breathing was deepening. There was a new warmth along his left side and someone's small hand was in his.

***

Lily awoke when the predawn light was graying the room—an unfamiliar room. She felt as if a fire was burning close to her right side. Someone was talking.

Neville was apologizing to Lauren. Then he was telling Sergeant Doyle in marvelously profane language what a damned foolish thing he had done by throwing his body in the path of a bullet intended for someone else. Then he was instructing a whole company of men to stay where they were in the pass, to ignore the murderous French fire from the hills to either side—to search for the marriage papers until they had found them. Then he was telling someone that he was by thunder going to get Lily alone at Vauxhall and just let Elizabeth try to stop him.

He was in a raging fever, with the accompanying delirium.

Lily had opened his nightshirt down the front and was bathing him with cool water when Elizabeth arrived. But apart from raising her eyebrows as she observed Lily clad only in her shift and then glancing at the left side of the bed, which had obviously been slept in, she made no comment. She quietly set about sharing the nursing. She had, she told Lily, made arrangements to cancel all lessons until further notice.

Lily steadfastly refused to leave the room until late in the afternoon. She knew from experience that many more men died from the fever that succeeded surgery than ever died from the wounds themselves. A bullet in the shoulder ought not to be a mortal wound, but the fever might well kill. She would not leave him. She would nurse him back to health or she would be by his side when he died.

But Elizabeth had been right—it was hard to nurse a man when one had an emotional involvement with him. When one loved him so deeply that one knew his death would leave a yawning emptiness in one's own life that could never again be filled. When one knew that he had taken the bullet intended for her. And when one did not understand why it had happened.

She had never told him that she loved him—or not since her wedding night. Now it might be too late. She could tell him so a dozen times during the course of the day—and she did so—but he could not understand.

She had never told him that to her dying day she would consider him to be her husband no matter what the church and the state had to say to the contrary—that she had never wavered in her fidelity to their marriage.

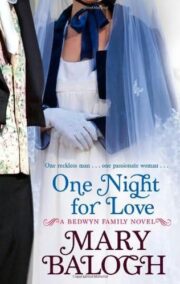

"One Night for Love" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "One Night for Love". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "One Night for Love" друзьям в соцсетях.