In the meantime here he was in Aquitaine – his brother’s lieutenant. It might well be that his brother would never be well enough to return and his future lay here on the continent.

Often he thought of Catherine. He could send for her, perhaps. But could he? The governess of his children, the wife of one of his squires who was serving now in the army!

Life was full of promise yet it was only promise. He wanted fulfilment.

First he must arrange the funeral of his nephew. Joan had wanted it to take place after they had left partly because she had been eager to get Edward home to England and partly because she feared that to attend it would bring such overpowering grief to the Prince that it would impair his health further.

It was a ceremonial occasion but those who would have felt real grief were no longer there.

No sooner was it over than news was brought to him that Montpoint in Périgord had surrendered to the French. He must therefore set out to regain the place. This occupied him for several weeks and it was not until the end of February that he had regained the town.

When he returned to Bordeaux it was clear to him and to everyone else that his heart was not in the task which had been assigned to him. He was holding Aquitaine for Edward. He wanted to rule in his own right not through another.

His brother, Edmund of Langley, joined him at Bordeaux and there also were Constanza and Isabella, the two daughters of Pedro the Cruel.

The spring had come. The weather was warm and the two brothers rode out to hunt or merely to enjoy the countryside with the two young women.

Constanza was serious minded. Her great object was to break out of exile and regain the crown of Castile which she declared was hers by right.

‘And so it is,’ agreed John, ‘and so should it be yours. This bastard Henry should be deposed and you should be welcomed back.’

‘He will never leave unless he is forced to,’ said Constanza. ‘If only I had the money to raise an army … I think the people would be with me. Surely they would wish to see the legitimate heir on the throne.’

John pondered this. He had been playing with the idea of suggesting to his father and his brother that the Salic law be established in England. It existed in France. That was why Edward was having to fight for the crown. The crown of France came to him through his mother but because of this law he had been set aside. That was what the war was about. John was now thinking of Lionel’s daughter, Philippa, who unless the Salic law was introduced would come after Richard and before him in the claim to the English throne.

He realised that this law would be considered illogical and there was no hope of its being introduced in England when the very recognition of such a law would render null and void Edward’s claim to the throne of France.

So therefore as he saw it there was ageing Edward who could not last more than two or three years at the most; the Black Prince whose recurring sickness suggested he too might not be long for this world; then there was this four-year-old boy, Richard, rather delicate and in any case little more than a baby. Then Philippa, daughter of Lionel, married to the Earl of March who no doubt had his ambitions. These were the ones who stood in line before John of Gaunt.

It could well be that the crown would never come his way. He had never won the popularity the Black Prince had enjoyed. He was not the great warrior that his brother had always been. He was not enamoured of war; he preferred to use the cunning moves of statecraft which were far less costly. The people were foolish; they never understood that such as he was would be so much better for the prosperity of the country than these great warriors whose aim was always to win glory in battle.

His great-grandfather had been a great king but he had wasted men and money in fighting the Scots – and what good had that brought England? His father had been obsessed by the French wars and what good was that bringing England? How much better it would have been to hold what he possessed in France – which needed continual watchfulness to be held – and to forget this wild dream of taking the crown of France. No, John of Gaunt would be a different kind of king if ever that glorious day came.

But how could it …with so many to stand between him and his ambition? The people would never accept him. They would be bemused by the sight of this pretty fair-haired boy or young Philippa – a Queen. They were ridiculously sentimental and they had never really taken to John of Gaunt. For one thing he had not been born in England. His brother Edward was Edward of Woodstock. They called him that sometimes. Edward the Black Prince. A magic name, and they would support his son however young he was. The crown of England seemed a long way from John of Gaunt.

But there was another crown which he might win.

Constanza had shown very clearly that she would be ready to marry the man who would help her win her heritage.

Constanza could make him King of Castile.

He talked the matter over with Edmund.

‘Constanza is determined to regain the crown of Castile,’ he said. ‘Methinks she looks to us, brother.’

‘I am sure she does.’

‘I have been thinking, Edmund, that I should like to be the King of Castile.’

Edmund clasped his brother’s hand.

‘There is nothing that would please me more, brother, than to see you Constanza’s husband. We should be near each other for the rest of our lives, for I have decided I shall marry Isabella.’

‘The younger sister …!’ began John, and Edmund laughed.

‘I am not ambitious as you are, John. I would be quite content to spend the rest of my days in a pleasant Court given over to the enjoyment of living, of which I declare, there is too little in our lives.’

John nodded. Edmund was easy-going, pleasure-loving, Lionel all over again. Good-natured, generous, loving music and poetry, Edmund had no great love of battle. It was unfortunate to be a son of the Plantagenets and to have this kind of temperament because there must always be a certain amount of fighting to be done. Men such as his father would have been horrified if Edmund had told him that he preferred to live quietly in some little Court surrounded by troubadours and poets rather than to fight to enhance the family’s prestige and gain new possessions.

John understood Edmund’s attitude; he did not share it by any means. He wanted the possessions and he would fight for them but he preferred to win them by other means – he would never be a great general like his father and elder brother. The battle for him was the means to an end; he had no joy in it for its own sake as these military heroes had.

‘I have not absolutely decided yet,’ he said. ‘I want to think about it.’

‘But why not, John? Constanza is an attractive woman. Moreover you want to be a king. That’s your chance.’

‘I know,’ said John. He could not explain that he did not want Constanza. He wanted Catherine Swynford. Even Edmund, who would have understood in some measure, would have laughed. Sons of kings did not marry governesses. Besides the woman had a husband already.

I am foolish to think of her, thought John, and yet … The fact was he could not stop thinking of her. He knew that as soon as he returned to England he would seek her out. He would have to be with her. He would not be able to keep his liaison secret from Constanza. How could one plan to marry one woman while one was thinking constantly of another?

What nonsense this was! Of course he must marry Constanza, and when he returned to England this feeling towards Catherine might have changed. It was long since he had seen her. Why was he hesitating? How could he marry Catherine? She had a husband. Could he be like David in placing Uriah the Hittite in the forefront of the battle?

Be reasonable, he admonished himself. Be sensible. Marry Constanza.

He sought her out without delay lest he should change his mind.

‘Constanza,’ he said. ‘If you marry me I will fight to regain your crown.’

Her joy was reflected in her face. She held out her hands and he seized them.

He drew her to him and kissed her.

He felt nothing for her, only a great sickness of heart because she was not Catherine.

It was springtime when the two brothers returned to England with their brides.

John and Constanza went to the Palace of the Savoy, riding through the streets and the people came out to see them.

There were mild cheers for the King and Queen of Castile as they were calling themselves.

Along by the river they rode and into the palace which had delighted John ever since it had come into his possession through his marriage to Blanche. Now he was thinking not so much of the grandeur of that magnificent pile of stones as to what he would find within.

Constanza was amused at his eagerness. She thought it was to see his children. It was not that he would not be delighted to see how they had grown during his absence; but what put that flush in his cheeks and shine in his eyes was the prospect of seeing Catherine again.

In the great hall those who served him in the palace were lined up to greet him and pay homage to the new Duchess of Lancaster who was also the self-styled Queen of Castile; and there were his children. He dared not look just yet at the tall graceful woman who stood holding young Henry’s hand.

Philippa had grown almost beyond recognition. Elizabeth too. And young Henry was a sturdy five-year-old.

John lifted his eyes from the children and looked at Catherine. She smiled serenely.

He felt a great impulse then to take her in his arms, to hold her to him … there before them all. She knew it and her smile was confident. Nothing could change the overwhelming attraction between them. Certainly not this dark-eyed bride from Castile.

‘And how are my son and daughters?’ asked John.

He was not looking at her but at the children but he was seeing her – the soft skin, the thick red hair which sprang so vitally from the smooth white forehead. He knew the texture of that skin and he longed to touch it.

‘We have seen the King,’ said Philippa.

‘Alice Perrers was with him,’ added Elizabeth; she was more outspoken than her sister.

‘Hush,’ said Philippa. ‘We are not supposed to talk of her.’

‘Must you talk of others when your father has just returned? And what has my son to say for himself?’

Henry told his father that he went hunting last week. ‘We caught a fine deer.’

‘Nothing has changed much since I have been away,’ said John. ‘You must meet the new Duchess. Constanza …’

The children were presented to their stepmother. The girls regarded her with suspicion, young Henry with interest.

‘May I present to you, Lady Swynford, their governess?’

Catherine curtseyed and Constanza gave her a cold nod.

Then John with Henry’s hand in his and the girls on the other side of him passed on.

At the earliest possible moment he sent for her.

When she came to his apartments, he was shaking with emotion.

‘I wished to see you, Lady Swynford, to hear from your lips how my children have fared during my absence.’

‘All is well with them, my lord,’ she answered calmly. ‘They are in good health, as you see, and progress at their lessons. Henry’s riding masters will give you a good account of his conduct I am sure …’

He was not listening. He was watching her intently.

‘I have longed to see you,’ he said quietly. ‘You have changed little. It has been so long.’

She lowered her eyes.

‘I must see you … alone … where we can be together.’

She lifted her eyes to his. ‘Is it possible, my lord, now?’

Of course it had been different before. Blanche had been dead. He was a widower then. Now he was just returned with a new bride.

‘I married for state reasons,’ he said. And was amazed at himself. Why should he, the son of the King, explain his reasons to a governess?

‘Yes,’ she answered. ‘I know it.’

‘You have a husband,’ he said, as though excusing himself for not marrying her. What did she do to him? She made a different man of him. She unnerved him; she bewitched him. He believed that had she been free he would have married her.

If he had what bliss that would have been. No subterfuge, they could have been together night and day.

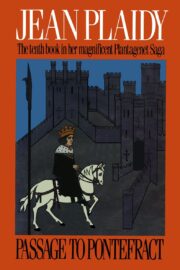

"Passage to Pontefract" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Passage to Pontefract". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Passage to Pontefract" друзьям в соцсетях.